The Story of the Romans (Yesterday's Classics) (24 page)

All his thoughts were about eating and drinking. He lived in great luxury at home; but he often invited himself out to dinner, breakfast, or supper, at the house of one of his courtiers, where he expected to be treated to the most exquisite viands.

Such was his love of eating, it is said, that when he had finished one good meal, he would take an emetic, so that he might begin at once on the next; and thus he was able to enjoy four dinners a day instead of one. This disgusting gluttony became so well know that many Romans made up their minds not to obey any longer a man whose habits were those of the meanest animals.

They therefore determined to select as emperor the general Vespasian, who had won many victories during the reigns of Claudius, Nero, Galba, and Otho, and who was now besieging Jerusalem. In obedience to the soldiers' wishes Vespasian left his son Titus to finish the siege, and sent an army toward Rome, which met and defeated the forces of Vitellius.

The greedy emperor cared little for the imperial title, and now offered to give it up, on condition that he should be allowed a sum of money large enough to enable him to end his life in luxury. When this was refused him, he made a feeble effort to defend himself in Rome.

Vespasian's army, however, soon forced its way into the city. Vitellius tried first to flee, and then to hide; but he was soon found and killed by the soldiers, who dragged his body through the streets, and then flung it into the Tiber.

The senate now confirmed the army's choice, and Vespasian became emperor of Rome. Although he had been wild in his youth, Vespasian now gave the best example to his people; for he spent all his time in thinking of their welfare, and in trying to improve Rome. He also began to build the Coliseum, the immense circus whose ruins can still be seen, and where there were seats for more than one hundred thousand spectators.

The Coliseum

While Vespasian was thus occupied at home, his son Titus had taken command of the army which was besieging the city of Jerusalem. As the prophets had foretold, these were terrible times for the Jews. There were famines and earthquakes, and strange signs were seen in the sky.

In spite of all these signs, Titus battered down the heavy walls, scaled the ramparts, and finally took the city, where famine and pestilence now reigned. The Roman soldiers robbed the houses, and then set fire to them. The flames thus started soon reached the beautiful temple built by Herod, and in spite of all that Titus could do to save it, this great building was burned to the ground.

Amid the lamentations of the Jews, the walls of the city were razed and the site plowed; and soon, as Christ had foretold, not one stone remained upon another. Nearly one million Jews are said to have perished during this awful siege, and the Romans led away one hundred thousand captives.

On his return to Rome, Titus was honored by a triumph. The books of the law and the famous golden candlestick, which had been in the temple at Jerusalem, were carried as trophies in the procession. The Romans also commemorated their victory by erecting the Arch of Titus, which is still standing. The carving on this arch represents the Roman soldiers carrying the booty, and you will see there a picture of the seven-branched candlestick which they brought home.

Vespasian reigned ten years and was beloved by all his subjects. He was taken ill at his country house, and died there. Even when the end was near, and he was too weak to stand, he bade his attendants help him to his feet, saying, "An emperor should die standing."

The Buried Cities

T

ITUS

,

the son of Vespasian, was joyfully received as his successor, and became one of the best rulers that Rome had ever seen. He was as good as he was brave; and, although he was not a Christian, he is known as one of the best men that ever lived, and could serve as an example for many people now.

He soon won the hearts of all his people, and he fully deserved the title which they gave him, "Delight of Mankind." True and just, Titus punished informers, false witnesses, and criminals, and made examples of all sinful people. But he was very generous, too, and very courteous and ready to do good. Whenever a whole day passed without his being able to help any one, he would exclaim with regret, "Alas, I have lost a day!"

It was fortunate that the Romans had so good an emperor at that time, for a very great calamity happened, which filled the hearts of all with horror.

You may remember that Spartacus and the revolted slaves fled at first to a mountain called Mount Vesuvius. Well, in those days this mountain was covered with verdure, and near its foot were the two rich and flourishing cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum. The people felt no fear of the mountain, because it was not then, as now, an active volcano.

But one day they began to feel earthquakes, the air grew hot and very sultry, smoke began to come out of the crater, and all at once, with an awful noise, a terrible eruption took place. Red-hot rocks were shot far up into the air with frightful force; great rivers of burning lava flowed like torrents down the mountain side; and, before the people could escape, Pompeii and Herculaneum were buried under many feet of ashes and lava.

Thousands of people died, countless homes were burned or buried, and much land which had formerly been very fertile was made barren and unproductive. Pliny, the naturalist, had been told of the strange, rumbling sounds which were heard in Vesuvius, and had journeyed thither from Rome to investigate the matter. He was on a ship at the time, but when he saw the smoke he went ashore near the mountain, and before long was smothered in the foul air.

Sixteen hundred years after the two cities were buried, an Italian began to dig a well in the place where Pompeii had once stood. After digging down to a depth of forty feet, he came across one of the old houses in a remarkable state of preservation.

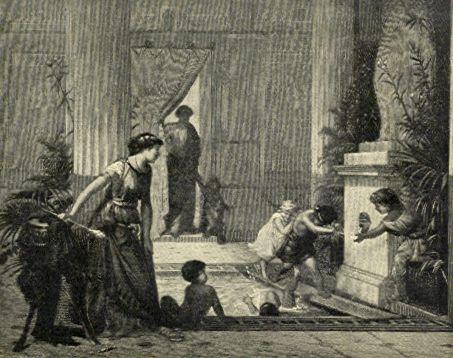

Interior of a House in Pompeii

Since then, the ruins have been partly dug out, and many treasures have been found there buried under the soil. The ruins of Pompeii and Herculaneum are visited every year by many travelers from all parts of the world. They go there to see how people lived in the days of the Roman emperors, and to admire the fragments of beautiful paintings, the statues, pottery, etc., which have been found there.

Most of the large houses in Pompeii had a central court or hall, in which was a large tank of fresh water. This was the coolest place in the house, and the children had great fun playing around the water and plunging in it.

When Pompeii was destroyed all Italy was saddened by the terrible catastrophe, but the Romans soon had cause to rejoice once more at the news of victories won abroad. A revolt in Britain was put down, and the people there soon learned to imitate their conquerors, and to build fine houses and solid roads.

The good emperor Titus died of a fever after a reign of about two years. His death was mourned by all his people, who felt that they would never have so good a friend again.

The Terrible Banquet

T

ITUS

was succeeded by his brother Domitian, who began his reign in a most praiseworthy way. Unfortunately, however, Domitian was a gambler and a lover of pleasure. He was lazy, too, and soon banished all the philosophers and mathematicians from Rome, saying that he had no use for such tiresome people.

No other emperor ever gave the people so many public shows. Domitian delighted in the circus, in races of all kinds, and in all athletic games and tests of skill. He was a good marksman and a clever archer. Such was his pride in his skill that he often forced a slave to stand up before him, at a certain distance, and then shot arrows between the fingers of his outspread hand. Of course this was very cruel, because if the emperor missed his aim, or if the man winced, it meant either maiming or death to the poor slave.

Domitian, however, was cruel in many things besides sport, and delighted in killing everything he could lay hands on. We are told that he never entered a room without catching, torturing, and killing every fly. One day a slave was asked whether the emperor were alone, and he answered: "Yes; there is not even a fly with him!"

Domitian's cruelty and vices increased with every day of his reign, and so did his vanity. As he wished to enjoy the honors of a triumph, he made an excursion into Germany, and came back to Rome, bringing his own slaves dressed to represent captives.

Jealous of the fame of Agricola, the general who had subdued Britain, Domitian summoned him home, under the pretext of rewarding him. While Agricola was in Rome, the northern barbarians made several invasions, and the King of the Dacians inflicted a severe defeat on the Roman legion.

So great, however, was the emperor's jealousy of his best general, that he made Agricola stay at home rather than let him win any more victories. Before many years, too, this great general was found dead, and no one knew the cause of his death; so the Romans all believed that Domitian had hired some one to murder him.

As Domitian was not brave enough to fight the Dacians himself, he bribed them to return home. Then, coming back to Rome, he had a triumph awarded him just as if he had won a great victory. Not content with these honors, he soon ordered that the Romans should worship him as a god, and had gold and silver statues of himself set up in the temples.

Domitian was never so happy as when he could frighten people, or cause them pain. You will therefore not be surprised to hear about the strange banquet, or dinner party, to which he once invited his friends.

When the guests arrived at the palace, they were led to a room all hung in black. Here they were waited upon by tiny servants with coal-black faces, hands, and garments. The couches, too, were spread with black, and before each guest was a small black column, looking like a monument, and bearing his name. The guests were waited upon in silence, and given nothing but "funeral baked meats," while mournful music, which sounded like a wail, constantly fell upon their ears.

Knowing how cruel and capricious Domitian could be, the guests fancied that their last hour had come, and that they would leave the banquet hall only to be handed over to the executioner's hands. Imagine their relief, therefore, when they were allowed to depart unharmed!

On the next day, the children who had waited upon them at table, and whose faces and hands had been blackened only for that occasion, came to bring them the little columns on which their names were inscribed. These, too, had lost their funeral hue, and the guests could now see that they were made of pure gold.

The Emperor's Tablets

S

OME

of the Roman legions, displeased at having so unworthy an emperor, revolted under their general Antonius. As he failed to please them, however, they did not fight very bravely for him, and his troops were completely defeated the first time they met the legions which still remained faithful to Domitian.

Although the soldiers had failed to get rid of Domitian, the cruel reign of that emperor was soon ended. He had married a wife by force, and she was known by the name of Domitia. Of course she could not love a husband who had taken her against her will. Domitian therefore grew tired of her, and wrote her name down upon the tablets where he was wont to place the names of the next persons to be slain.

Domitia found these tablets. Seeing her own name among several others, she carried the list to two pretorian guards who were to die also, and induced them to murder Domitian. Under the pretext of revealing a conspiracy against him, these men sent a freedman into the imperial chamber.

While Domitian was eagerly reading a paper upon which the names of the conspirators were written, this freedman suddenly drew out a dagger, which he had hidden beneath his robe, and dealt the emperor a mortal wound.

Domitian fell, loudly calling for help. The pretorian guard rushed in at this sound, but, instead of killing the freedman, they helped him dispatch their master, who had reigned about fifteen years, but had not made a single friend.