The Story of the Greeks (Yesterday's Classics) (2 page)

In Egypt there were at that time a number of learned men. They were acquainted with many of the arts and sciences, and recorded all they knew in a peculiar writing of their own invention. Their neighbors, the Phœnicians, whose land also bordered on the Mediterranean Sea, were quite civilized too; and as both of these nations had ships, they soon began to sail all around that great inland sea.

As they had no compass, the Egyptian and Phœnician sailors did not venture out of sight of land. They first sailed along the shore, and then to the islands which they could see far out on the blue waters.

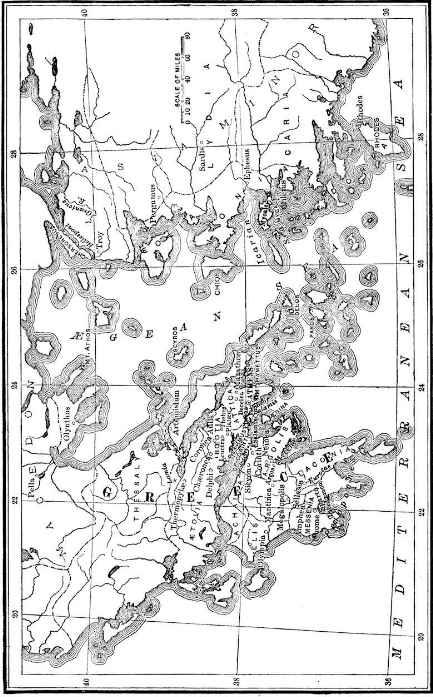

When they had come to one island, they could see another still farther on; for, as you will see on any map, the Mediterranean Sea, between Greece and Asia, is dotted with islands, which look like stepping stones going from one coast to the other.

Advancing thus carefully, the Egyptians and Phœnicians finally came to Greece, where they made settlements, and began to teach the Pelasgians many useful and important things.

Map of Ancient Greece

The Deluge of Ogyges

T

HE

first Egyptian who thus settled in Greece was a prince called Inachus. Landing in that country, which has a most delightful climate, he taught the Pelasgians how to make fire and how to cook their meat. He also showed them how to build comfortable homes by piling up stones one on top of another, much in the same way as the farmer makes the stone walls around his fields.

The Pelasgians were intelligent, although so uncivilized; and they soon learned to build these walls higher, in order to keep the wild beasts away from their homes. Then, when they had learned the use of bronze and iron tools, they cut the stones into huge blocks of regular shape.

These stone blocks were piled one upon another so cleverly that some of the walls are still standing, although no mortar was used to hold the stones together. Such was the strength of the Pelasgians, that they raised huge blocks to great heights, and made walls which their descendants declared must have been built by giants.

As the Greeks called their giants Cyclops, which means "round-eyed," they soon called these walls Cyclopean; and, in pointing them out to their children, they told strange tales of the great giants who had built them, and always added that these huge builders had but one eye, which was in the middle of the forehead.

Some time after Inachus the Egyptian had thus taught the Pelasgians the art of building, and had founded a city called Argos, there came a terrible earthquake. The ground under the people's feet heaved and cracked, the mountains shook, the waters flooded the dry land, and the people fled in terror to the hills.

In spite of the speed with which they ran, the waters soon overtook them. Many of the Pelasgians were thus drowned, while their terrified companions ran faster and faster up the mountain, nor stopped to rest until they were quite safe.

Looking down upon the plains where they had once lived, they saw them all covered with water. They were now forced to build new homes; but when the waters little by little sank into the ground, or flowed back into the sea, they were very glad to find that some of their thickest walls had resisted the earthquake and flood, and were still standing firm.

The memory of the earthquake and flood was very clear, however. The poor Pelasgians could not forget their terror and the sudden death of so many friends, and they often talked about that horrible time. As this flood occurred in the days when Ogyges was king, it has generally been linked to his name, and called the Deluge (or flood) of Ogyges.

The Founding of Many Important Cities

S

OME

time after Inachus had built Argos, another Egyptian prince came to settle in Greece. His name was Cecrops, and, as he came to Greece after the Deluge of Ogyges, he found very few inhabitants left. He landed, and decided to build a city on a promontory northeast of Argos. Then he invited all the Pelasgians who had not been drowned in the flood to join him.

The Pelasgians, glad to find such a wise leader, gathered around him, and they soon learned to plow the fields and to sow wheat. Under Cecrops' orders they also planted olive trees and vines, and learned how to press the oil from the olives and the wine from the grapes. Cecrops taught them how to harness their oxen; and before long the women began to spin the wool of their sheep, and to weave it into rough woolen garments, which were used for clothing, instead of the skins of wild beasts.

After building several small towns in Attica, Cecrops founded a larger one, which was at first called Cecropia in honor of himself. This name, however, was soon changed to Athens to please Athene (or Minerva), a goddess whom the people worshiped, and who was said to watch over the welfare of this her favorite city.

Athene

When Cecrops died, he was followed by other princes, who continued teaching the people many useful things, such as the training and harnessing of horses, the building of carts, and the proper way of harvesting grain. One prince even showed them how to make beehives, and how to use the honey as an article of food.

As the mountain sides in Greece are covered with a carpet of wild, sweet-smelling herbs and flowers, the Greek honey is very good; and people say that the best honey in the world is made by the bees on Mount Hymettus, near Athens, where they gather their golden store all summer long.

Shortly after the building of Athens, a Phœnician colony, led by Cadmus, settled a neighboring part of the country, called Bœotia, where they founded the city which was later known as Thebes. Cadmus also taught the people many useful things, among others the art of trade (or commerce) and that of navigation (the building and using of ships); but, best of all, he brought the alphabet to Greece, and showed the people how to express their thoughts in writing.

Almost at the same time that Cadmus founded Thebes, an Egyptian called Danaus came to Greece, and settled a colony on the same spot where that of Inachus had once been. The new Argos rose on the same place as the old; and the country around it, called Argolis, was separated from Bœotia and Attica only by a long narrow strip of land, which was known as the Isthmus of Corinth.

Danaus not only showed the Pelasgians all the useful arts which Cadmus and Cecrops had taught, but also helped them to build ships like that in which he had come to Greece. He also founded religious festivals or games in honor of the harvest goddess, Demeter. The women were invited to these games, and they only were allowed to bear torches in the public processions, where they sang hymns in honor of the goddess.

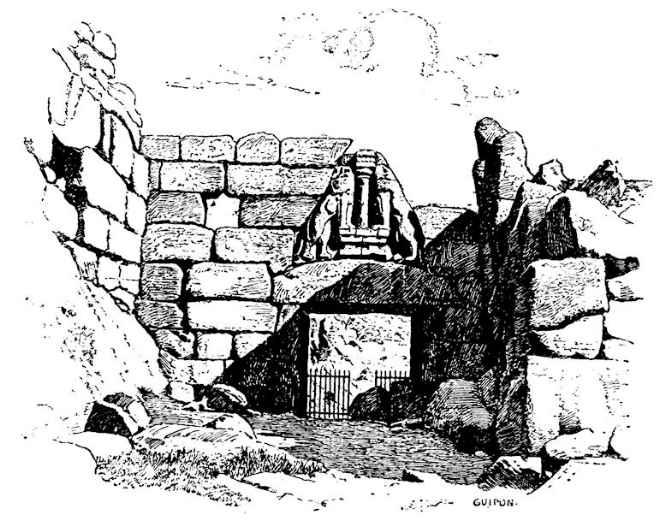

The descendants of Danaus long ruled over the land; and one member of his family, Perseus, built the town of Mycenæ on a spot where many of the Pelasgian stone walls can still be seen.

The Pelasgians who joined this young hero helped him to build great walls all around his town. These were provided with massive gateways and tall towers, from which the soldiers could overlook the whole country, and see the approach of an enemy from afar.

The Lion Gate, Mycenæ

This same people built tombs for some of the ancient kings, and many treasure and store houses. These buildings, buried under earth and rubbish, were uncovered a few years ago. In the tombs were found swords, spears, and remains of ancient armor, gold ornaments, ancient pieces of pottery, human bones, and, strangest of all, thin masks of pure gold, which covered the faces of some of the dead.

Thus you see, the Pelasgians little by little joined the new colonies which came to take possession of the land, and founded little states or countries of their own, each governed by its own king, and obeying its own laws.

Story of Deucalion

T

HE

Greeks used to tell their children that Deucalion, the leader of the Thessalians, was a descendant of the gods, for each part of the country claimed that its first great man was the son of a god. It was under the reign of Deucalion that another flood took place. This was even more terrible than that of Ogyges; and all the people of the neighborhood fled in haste to the high mountains north of Thessaly, where they were kindly received by Deucalion.

When all danger was over, and the waters began to recede, they followed their leader down into the plains again. This soon gave rise to a wonderful story, which you will often hear. It was said that Deucalion and his wife Pyrrha were the only people left alive after the flood. When the waters had all gone, they went down the mountain, and found that the temple at Delphi, where they worshiped their gods, was still standing unharmed. They entered, and, kneeling before the altar, prayed for help.

A mysterious voice then bade them go down the mountain, throwing their mother's bones behind them. They were very much troubled when they heard this, until Deucalion said that a voice from heaven could not have meant them to do any harm. In thinking over the real meaning of the words he had heard, he told his wife, that, as the Earth is the mother of all creatures, her bones must mean the stones.

Deucalion and Pyrrha, therefore, went slowly down the mountain, throwing the stones behind them. The Greeks used to tell that a sturdy race of men sprang up from the stones cast by Deucalion, while beautiful women came from those cast by Pyrrha.

The country was soon peopled by the children of these men, who always proudly declared that the story was true, and that they sprang from the race which owed its birth to this great miracle. Deucalion reigned over this people as long as he lived; and when he died, his two sons, Amphictyon and Hellen, became kings in his stead. The former staid in Thessaly; and, hearing that some barbarians called Thracians were about to come over the mountains and drive his people away, he called the chiefs of all the different states to a council, to ask their advice about the best means of defense. All the chiefs obeyed the summons, and met at a place in Thessaly where the mountains approach the sea so closely as to leave but a narrow pass between. In the pass are hot springs, and so it was called Thermopylæ, or the Hot Gateway.

The chiefs thus gathered together called this assembly the Amphictyonic Council, in honor of Amphictyon. After making plans to drive back the Thracians, they decided to meet once a year, either at Thermopylæ or at the temple at Delphi, to talk over all important matters.

Story of Dædalus and Icarus

H

ELLEN

,

Deucalion's second son, finding Thessaly too small to give homes to all the people, went southward with a band of hardy followers, and settled in another part of the country which we call Greece, but which was then, in honor of him, called Hellas, while his people were called Hellenes, or subjects of Hellen.

When Hellen died, he left his kingdom to his three sons, Dorus, Æolus, and Xuthus. Instead of dividing their father's lands fairly, the eldest two sons quarreled with the youngest, and finally drove him away. Homeless and poor, Xuthus now went to Athens, where he was warmly welcomed by the king, who not only treated him very kindly, but also gave him his daughter in marriage, and promised that he should inherit the throne.