The Story of the Greeks (Yesterday's Classics) (13 page)

The daring and force of the Greek attack so confused the Persians, that they began to give way. This encouraged the Greeks still further, and they fought with such bravery that soon the army of The Great King was completely routed.

Hippias, fighting at the head of the Persian army, was one of the first to die; and when the Persians saw their companions falling around them like ripe grain under the mower's scythe, they were seized with terror, rushed toward the sea, and embarked in their vessels in great haste.

The Athenians followed the enemy closely, killing all they could reach, and trying to prevent them from embarking and so escaping their wrath. One Greek soldier even rushed down into the waves, and held a Persian vessel which was about to push off.

The Persians, anxious to escape, struck at him, and chopped off his hand; but the Greek, without hesitating a moment, grasped the boat with his other hand, and held it fast. In their hurry to get away, the Persians struck off that hand too; but the dauntless hero caught and held the boat with his strong teeth, and died beneath the repeated blows of the enemy without having once let go. Thanks to him, not one of those enemies escaped.

The victory was a glorious one. The whole Persian force had been routed by a mere handful of men; and the Athenians were so proud of their victory, that they longed to have their fellow-citizens rejoice with them.

One of the soldiers, who had fought bravely all day, and who was covered with blood, said he would carry the glad news, and, without waiting a moment, he started off at a run.

Such was his haste to reassure the Athenians, that he ran at his utmost speed, and reached the city in a few hours. He was so exhausted, however, that he had barely time to gasp out, "Rejoice, we have conquered!" before he sank down in the middle of the market place, dead.

The Greeks, having no more foes to kill, next began to rob the tents, where they found so much booty that each man became quite rich. Then they gathered up their dead, and buried them honorably on the battlefield, at a spot where they afterward erected ten small columns bearing the names of all who had lost their lives in the conflict.

Just as all was over, the Spartan force came rushing up, ready to give their promised aid. They were so sorry not to have had a chance to fight also, and to have missed a share in the glory, that they vowed they would never again allow any superstition to prevent their striking a blow for their native land whenever the necessity arose.

Miltiades, instead of permitting his weary soldiers to camp on the battlefield, and celebrate their victory by a grand feast, next ordered them to march on to the city, so as to defend it in case the Persian fleet came to attack it.

The troops had scarcely arrived in town and taken up their post there, when the Persian vessels came in; but when the soldiers attempted to land, and saw the same men ready to meet them, they were so dismayed that they beat a hasty retreat without striking another blow.

Miltiades' Disgrace

T

HE

victory of Marathon was a great triumph for the Athenians; and Miltiades, who had so successfully led them, was loaded with honors. His portrait was painted by the best artist of the day, and it was placed in one of the porticos of Athens, where every one could see it.

At his request, the main part of the booty was given to the gods, for the Greeks believed that it was owing to divine favor that they had conquered their enemies. The brazen arms and shields which they had taken from the ten thousand Persians killed were therefore melted, and formed into an immense statue of Athene, which was placed on the Acropolis, on a pedestal so high that the glittering lance which the goddess held could be seen far out at sea when the sunbeams struck its point.

The Athenians vented their triumph and delight in song and dance, in plays and works of art of all kinds; for they wished to commemorate the glorious victory which had cost them only a hundred and ninety men, while the enemy had lost ten thousand.

One of their choicest art treasures was made by Phidias, the greatest sculptor the world has ever known, out of a beautiful block of marble which Darius had brought from Persia. The great king had intended to set it up in Athens as a monument of his victory over the Greeks. It was used instead to record his defeat; and when finished, the statue represented Nemesis, the goddess of retribution, whose place it was to punish the proud and insolent, and to make them repent of their sins.

Miltiades was, as we have seen, the idol of the Athenian people after his victory at Marathon. Unfortunately, however, they were inclined to be fickle, and when they saw that Miltiades occupied such a high rank, many began to envy him.

Themistocles was particularly jealous of the great honors that his friend had won. His friends soon noticed his gloomy, discontented looks; and when they inquired what caused them, Themistocles said it was because the thought of the trophies of Miltiades would not let him sleep. Some time after, when he saw that Miltiades was beginning to misuse his power, he openly showed his dislike.

Not very far from Athens, out in the Ægean sea, was the island of Paros. The people living there were enemies of Miltiades, and he, being sole head of the fleet, led it thither to avenge his personal wrongs.

The expedition failed, however; and Miltiades came back to Athens, where Themistocles and the indignant citizens accused him of betraying his trust, tried him, and convicted him of treason.

Had they not remembered the service that he had rendered his country in defeating the Persians at Marathon, they would surely have condemned him to death. As it was, the jury merely sentenced him to pay a heavy fine, saying that he should remain in prison until it was paid.

Miltiades was not rich enough to raise this large sum of money, so he died in prison. His son Cimon went to claim his body, so that he might bury it properly; but the hard-hearted judges refused to let him have it until he had paid his father's debt.

Thus forced to turn away without his father's corpse, Cimon visited his friends, who lent him the necessary money. Miltiades, who had been the idol of the people, was now buried hurriedly and in secret, because the ungrateful Athenians had forgotten all the good he had done them, and remembered only his faults.

Aristides the Just

T

HE

Athenians were very happy, because they thought, that, having once defeated the Persians, they need fear them no more. They were greatly mistaken, however. The Great King had twice seen his preparations come to naught and his plans ruined, but he was not yet ready to give up the hope of conquering Greece.

On the contrary, he solemnly swore that he would return with a greater army than ever, and make himself master of the proud city which had defied him. These plans were suspected by Themistocles, who therefore urged the Athenians to strengthen their navy, so that they might be ready for war when it came.

Aristides, the other general, was of the opinion that it was useless to build any more ships, but that the Athenians should increase their land forces. As each general had a large party, many quarrels soon arose. It became clear before long, that, unless one of the two leaders left the town, there would be an outbreak of civil war.

All the Athenians, therefore, gathered together in the market place, where they were to vote for or against the banishment of one of the leaders. Of course, on this great occasion, all the workmen left their labors, and even the farmers came in from the fields.

Aristides was walking about among the voters, when a farmer stopped him. The man did not know who he was, but begged him to write his vote down on the shell, for he had never even learned to read.

"What name shall I write?" questioned Aristides.

"Oh, put down 'Aristides,' " answered the farmer.

"Why do you want him sent away? Has he ever done you any harm?" asked Aristides.

"No," said the man, "but I'm tired of hearing him called the Just."

Without saying another word, Aristides calmly wrote his own name on the shell. When the votes were counted, they found six thousand against him: so Aristides the Just was forced to leave his native city, and go away into exile.

This was a second example of Athenian ingratitude; for Aristides had never done anything wrong, but had, on the contrary, done all he could to help his country. His enemies, however, were the men who were neither honest nor just, and who felt that his virtues were a constant rebuke to them; and this was the very reason why they were so anxious to get him out of the city.

Two Noble Spartan Youths

D

ARIUS

was in the midst of his preparations for a third expedition to Greece, when all his plans were cut short by death. His son and successor, Xerxes I., now became king of Persia in his stead.

The new monarch was not inclined to renew the struggle with the Greeks; but his courtiers and the exiled Greeks who dwelt in his palace so persistently urged him to do it, that he finally consented. Orders were then sent throughout the kingdom to get ready for war, and Xerxes said that he would lead the army himself.

During eight years the constant drilling of troops, manufacture of arms, collecting of provisions, and construction of roads, were kept up all through Asia. A mighty fleet lay at anchor, and the king was almost ready to start. Rumors of these great preparations had, of course, come to the ears of the Greeks. All hearts were filled with trouble and fear; for the coming army was far larger than the one the Athenians had defeated at Marathon, and they could not expect to be so fortunate again.

When the Spartans saw the terror of the people, they regretted having angered the king by killing the Persian messengers, and wondered what they could do to disarm his wrath. Two young men, Bulis and Sperthias, then nobly resolved to offer their lives in exchange for those that had been taken.

They therefore set out for Persia, and, having obtained permission to enter the palace, appeared before the king. Here the courtiers bade them fall down before the monarch, and do homage to him, as they saw the others do. But the proud young men refused to do so, saying that such honor could be shown only to their gods, and that it was not the custom of their country to humble themselves thus. Xerxes, to the surprise of his courtiers, did not at all resent their refusal to fall down before him, but kindly bade them make their errand known.

Thus invited to speak, one of them replied, "King of Persia, some years ago our people killed two of your father's messengers. It was wrong to touch an ambassador, we know. You are about to visit our country to seek revenge for this crime. Desist, O king! For we have come hither, my friend and I, to offer our lives in exchange for those our people have taken. Here we are! Do with us as you will."

Xerxes was filled with admiration when he heard this speech, and saw the handsome youths standing quietly before him, ready to die to atone for their country's wrong. Instead of accepting their offer, he loaded them with rich gifts, and sent them home unharmed, telling them he would not injure the innocent, for he was more just than the Lacedæmonians.

But a few months later, when his preparations were complete, Xerxes set out with an army which is said to have numbered more than two million fighting men. As they were attended by slaves and servants of all kinds, some of the old historians say that ten millions of human beings were included in this mighty host.

The Great Army

X

ERXES

'

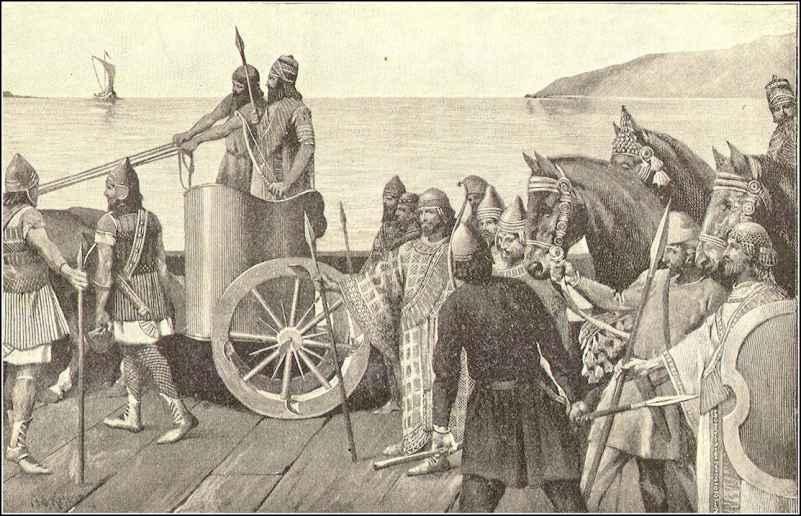

army marched in various sections across Asia Minor, and all the forces came together at the Hellespont. Here the king had ordered the building of two great bridges,—one for the troops, and the other for the immense train of baggage which followed him.

These bridges were no sooner finished than a rising storm entirely destroyed them. When Xerxes heard of the disaster, he not only condemned the unlucky engineers to death, but also had the waves flogged with whips, and ordered chains flung across the strait, to show that he considered the sea an unruly slave, who should be taught to obey his master.

Then, undaunted by his misfortune, the King of Persia gave orders for the building of new bridges; and when they were finished, he reviewed his army from the top of a neighboring mountain.

The sight must have been grand indeed, and the courtiers standing around were greatly surprised when they saw their master suddenly burst into tears. When asked the cause of his sorrow, Xerxes answered, "See that mighty host spread out as far as eye can reach! I weep at the thought that a hundred years hence there will be nothing left of it except, perhaps, a handful of dust and a few moldering bones!"

Crossing the Hellespont

The king was soon comforted, however, and crossed the bridge first, attended by his bodyguard of picked soldiers, who were called the Immortals because they had never suffered defeat. All the army followed him, and during seven days and nights the bridge resounded with the steady tramp of the armed host; but, even when the rear guard had passed over the Hellespont, there were still so many slaves and baggage wagons, that it took them a whole month to file past.