The Small House Book (10 page)

Read The Small House Book Online

Authors: Jay Shafer

12) Your interior wall finish can now

be hung. I generally use thin, knotty

pine tongue-and-groove paneling be-

cause it is so light and easy to install,

but drywall and other materials will

work, too, so long as you do not ex-

ceed your trailer’s weight limit.

13) If your windows and doors are

not in place by now, then this would

be the time to insert them. You can

also start building and/or installing

any cabinetry and built-ins you in-

tend to include.

14) Put your integral appliances in

place and trim your edges. I do tend

to put the screws aside and use nails

and glue for this part. Finish work is,

by far, the most time-consuming part

of the entire building process, but,

when it is done, your house is done,

too. Make yourself at home.

76

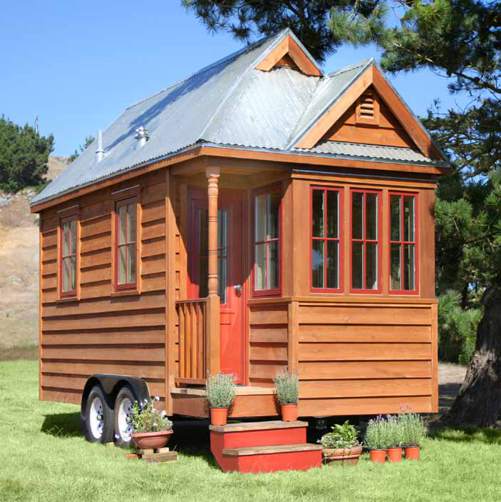

The finished product (right)

Subtractive Design

A well-designed little house is like an oversized house with the unusable

parts removed. Such refinement is achieved through subtractive design —

the systematic elimination of all that does not contribute to the intended func-

tion of a composition. In the case of residential architecture, everything not

enhancing the quality of life within a dwelling must go. Anything not working

to this end works against it. Extra bathrooms, bedrooms, gables and extra

space require extra money, time and energy from the occupant(s). Super-

fluous luxury items are a burden. A simple home, unfettered by extraneous

gadgets, is the most effective labor-saving device there is.

Subtractive design is used in disciplines ranging from industrial design to civil

engineering. In machine design, its primary purpose is demonstrated with

particular clarity. The more parts there are in a piece of machinery, the more

inefficient it will be. This is no less true of a home than it is of an engine.

Remembering Common Sense

Most of our new houses are really not designed at all, but assembled without

much thought for their ultimate composition. Architects seldom have anything

to do with the process. Instead, a team of marketing engineers comes up

with a product that will bring in more money at less cost to the developer. The

team’s job is to devise a cheap structure that people will actually pay good

money for. Low-grade, vinyl siding, ornamental gables and asphalt shingles

have become their preferred medium. Adding extra square footage is about

the cheapest, easiest way there is to increase a property’s market value, so it

is applied liberally without any apparent attempt to make the additional space

particularly useful. The final product is almost always a bulky conglomeration

78

of parts without cohesion — a success, by industry standards, where over-

sized invariably equals big profits.

Even when left to certified architects, the design of our homes can some-

times be less than sensible. Too frequently, a licensed architect’s self-per-

ceived need for originality takes precedence over the real needs of his or her

clients. Common sense is abandoned for frivolous displays of talent. Where

a straight gable would make the most sense, a less savvy architect will throw

in a few cantilevers and an extra dormer, just for show. Subtractive design

is abandoned for hopes of personal recognition and for what is likely to be a

very leaky house. Common sense is an inherent part of all great architecture.

Sadly, this crucial resource has become anything but common in the creation

of residential America.

Certainly the most famous example of those whose aspirations for a good

name took precedence over good design was Frank Lloyd Wright. Wright

was fond of innovative methods and extravagant forms. Those novel houses

that once earned him recognition as a peerless innovator have since earned

him another kind of reputation. Leaks are a part of many Wright houses.

Wright has become infamous not only for his abundant drips but for his im-

pudent dismissal of their significance. “If the roof doesn’t leak,” he professed,

“the architect hasn’t been creative enough.” And to those clients who dared

to complain about seepage, he would repeatedly quip, “That’s how you can

tell it’s a roof.”

79

Subtractive design is integral to, and nearly synonymous with, vernacular

design. Both entail planning a home that will satisfy its inhabitants’ domestic

needs without far exceeding them. This is also what is known as common

sense. When applied to buildings, the word “vernacular” in fact means “com-

mon”: that is to say “ordinary” and “of the people.” In contrast to housing that

is made by professionals for profit or fame, vernacular housing is designed

by ordinary folks simply striving to house themselves by the most proven and

effective means available.

Webster’s defines

vernacular

as “architectural expression employing the

commonest forms, materials, and decorations” (

Webster’s Third New Inter-

national Dictionary,

G. and C. Merriam Co. 1966. p. 2544). If a particular type of roof works better than any other, then that is what is used. In short,

vernacular architecture is not the product of invention, but of evolution—its

parts plucked from the great global stew pot of common knowledge and com-

mon forms. Anything is fair game so long as it has been empirically proven to

work well and withstand the test of time. By using only tried-and-true forms

and building practices, such design successfully avoids the multitude of post-

occupancy problems typical of more “innovative” architecture.

The vernacular home does not preclude modern conveniences. There are,

after all, better ways to insulate these days than with buffalo skins. The ver-

nacular designer appropriates the best means currently available to meet

human needs, but, technology is, of course, employed only where it will en-

hance the quality of life within a dwelling and not cause undue burden.

80

Mendocino gable (right)

All Natural

What the subtractive process requires, more than anything else, is a firm

understanding of necessity. Knowledge of universal human needs and the

archetypal forms that satisfy them is a prerequisite for the practice of good

design. This knowledge is available to anyone willing to pay attention.

A vernacular architect who has come across a photo of a Kirghizian yurt

and encountered a Japanese unitized bathroom and a termite mound while

traveling does not set out to build a yurt with a unitized bathroom and termite

inspired air conditioning just to show what he has learned. He retains the

forms for a time when necessity demands their use.

Vernacular architects do not strive to produce novel designs for novelty’s

sake. Necessity must be allowed to dictate form. The architect’s primary job

is to get out of its way. It might seem that such a process would produce a

monotonously limited variety of structures, but, in fact, there is infinite varia-

tion within the discipline. Vernacular architecture is as diverse as the climates

and cultures that produce it. The buildings in a particular region may all look

similar as they have all resulted from the same set of socionatural conditions,

but within these boundaries, there is also plenty of room for variance. With

the big problems of design already resolved by the common sense of their

predecessors, vernacular architects are left free to focus on the specifics of

the project at hand. Instead of reinventing the wheel, they are left to fine-tune

the spokes.

82

Symbolic Meaning

Vernacular architects have at their disposal not only what they have assimil-

ated from books, travel and the work of their ancestors but a lot of hard-wired

knowledge as well. Human beings have an innate understanding of certain

forms. We are born liking some shapes more than others, and our favorites

turn up frequently in the art of young children and in every culture. Among

these is the icon representing our collective idea of home. Everyone will un-

doubtedly recognize the depiction of a structure with a pitched roof, a chim-

ney accompanied by a curlicue of smoke and a door flanked by mullioned

windows. Children draw this as repeatedly and as spontaneously as they do

faces and animals. It represents our shared idea of home, and, not supris-

ingly, it includes some of the most essential parts of an effective house. With

little exception, a pitched roof to deflect the elements, with a well-marked

entrance leading into a warm interior, with a view to the world outside are ex-

actly what are necessary to a freestanding home. For a vernacular designer,

any deviation from this ideal is dictated by the particular needs posed by local

climate.

The symbolic meaning of common architectural shapes is as universal as the

use of the shapes themselves. Just as surely as we look for meaning in our

everyday world, the most common things in our world do become meaning-

ful. That the symbolism behind these objects is virtually the same from culture

to culture may say something about the nature of our less corporal desires.

It seems necessary that we see ourselves as part of an undivided universe.

Through science, religion, and art, we strive to make this connection. On an

intuitive level, home reminds us that the self and its environment are inextri-

cable. Archetypes like the pierced gable are not contrived, but rather turn up

naturally wherever necessity is allowed to dictate form and its content.

83

Mac Callum House in Mendocino ,CA

84

It just so happens that the most practical shapes are also the most symbolic-

ally loaded. Those forms best-suited to our physical needs have come to

hold special meaning for us. The standard gabled roof not only represents

our most primal idea of shelter, but also embodies the most universal of all

abstract concepts, that of All-as-One. This theme has been the foundation for

virtually every religion and government in history, and there may very well be

an illustration of it in your purse or wallet at this very moment.

The image of the pyramid on the back of the U.S. dollar represents the four

sides of the universe (All) culminating at their apex as the eye of God (One).