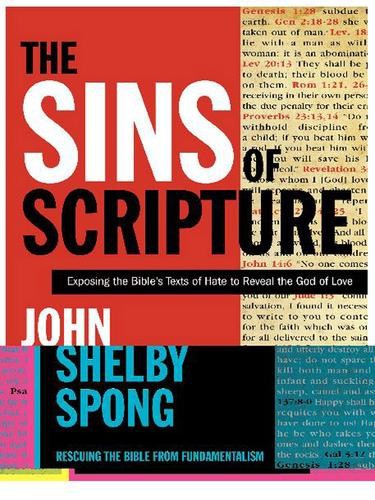

The Sins of Scripture

Read The Sins of Scripture Online

Authors: John Shelby Spong

THE

SINS

OF

SCRIPTURE

Exposing the Bible’s Texts of Hate to Reveal the God of Love

SHELBY

SPONG

For

CHRISTINE MARY SPONG

My Partner

in Every Sense

of the Word

Chapter 1.

Why This Book, This Theme, This Author

Chapter 2.

A Claim That Cannot Endure 15

Chapter 3.

The Ethics of Overbreeding

Chapter 4.

The Virtue of Birth Control

Chapter 5.

The Earth Fights Back

Chapter 6.

Bad Theology Creates Bad Ecology

Chapter 7.

Creation:

The Woman Is Not Made in the Image of God

Chapter 8.

Sexism in Christian History

Chapter 9.

The Woman as the Source of Evil

Chapter 10.

Menstruation and the Male Fear of Blood

Chapter 11.

Recasting the Negativity

Chapter 12.

The Ecclesiastical Battle over Homosexuality:

Intense, Irrational, Threatening and Hysterical

Chapter 13.

The Holiness Code from the Book of Leviticus

Chapter 14.

The Story of Sodom

Chapter 15.

The Homophobia of Paul

Chapter 16.

The Appeal in the Text “Spare the Rod”

Chapter 17.

Violence Is Always Violent, Whether the Victim Be a Child or an Adult

Chapter 18.

God as Judge:

Searching for the Source of the Human Need to Suffer

Chapter 19.

God as Divine Child Abuser:

The Sadomasochism in the Heart of Christianity

Chapter 20.

Moving Beyond the Demeaning God into the God of Life

Chapter 21.

Searching for the Origins of Christian Anti-Semitism

Chapter 22.

Anti-Semitism in the Gospels

Chapter 23.

The Role of Judas Iscariot in the Rise of Anti-Semitism

Chapter 24.

The Circumstances That Brought Judas into the Jesus Story

Chapter 25.

The Symptoms:

Conversion, Missionary Expansion and Religious Bigotry

Chapter 26.

Creedal Development in the Christian Church

Chapter 27.

Since I Have the Truth, “No One Comes to the Father, but by Me”

Chapter 28.

My Vision of an Interfaith Future

Chapter 29.

The Hebrew Scriptures Come into Being

Chapter 30.

Escaping the Limits of the Epic:

The Prophets, the Writings, the Dream

Chapter 31.

Jesus and the Jewish Epic

Chapter 32.

Jesus Beyond Religion:

The Sign of the Kingdom of God—the Epic Universalized and Humanized

Several years ago we were enjoying an evening with friends, watching the sunset from the deck of their summer home on Fire Island off the southern shore of New York State. I was due to retire in six months and our conversation turned not unnaturally to that issue and what retirement now means, when many people are living healthy, productive lives for twenty or thirty years after the end of their “working” careers. Retirement is no longer appropriately viewed as one or two years sitting in a rocking chair looking back on life. It was then that our hosts, Phoebe and Jack Ballard, introduced my wife and me to the concept of the “third half of life.” I was intrigued with this phrase, which the Ballards had used while leading retirement conferences. Their thesis was that if this part of life was to be as long, rewarding and satisfying as the first two halves of our lives had been, it needed to be given similar thoughtful and intentional planning. It was a new and exciting idea.

My father died at age fifty-four; his father at a similar age. Consequently I was not programmed to think in terms of longevity. Yet when I retired as the bishop of Newark I was sixty-eight years old. I had served for twenty-four wonderful and exciting years in that dynamic, mind-stretching and life-giving community of faith. I assumed that it was time to end my professional career and to step out of public life. I had no intention of behaving like many retired bishops who are not able to give up their former symbols of power and influence and thus succeed only in making the lives of their successors miserable. The new bishop of Newark, a good friend and a very able priest, would not have to put up with that. So I severed all connections other than Sunday worship that I had with the Episcopal Church I had served in my forty-five-year career and that I still love very deeply. I was sure I would miss being the bishop, but I intuitively knew that it would be the people with whom I had worked so closely that I would miss rather than the power or position of that office. What I did not know, however, was where I would direct my energies in the future. I had to feel my way into that.

Today, from a vantage point five years removed from my life as the bishop of Newark, I am happy to say that this first part of the “third half of life” has been the most exciting, the most enjoyable and perhaps even the most creative of all the years that I have known. If this is what the rest of life looks and feels like, then it is the greatest and most incredible part of life’s various adventures.

I originally intended for my last published book to be my autobiography:

Here I Stand: My Struggle for a Christianity of Integrity, Love, and Equality

. Surely, I thought and stated, “one does not write another book after an autobiography has been published.” Autobiographies come at the end of life. The first chapters describe one’s origins and the last chapter should be the summation of one’s life from a vantage point near its end. Perhaps someone might even add to certain autobiographies a postscript to take note of the author’s death. My autobiography was set and programmed to come out as I retired, and it was to announce my intended destiny to walk quietly into the sunset! That, however, has not been my experience. Perhaps Ed Stannard, writing about my retirement in the national Episcopal newspaper called

Episcopal Life

(February 2000), had it right when he concluded his article with these words: “His life will be different but don’t expect him to keep quiet.”

The first sign that I might be in for a surprise came when a letter arrived prior to my retirement inviting me to become the William Belden Noble Lecturer at Harvard University during the first semester of the year 2000. Indeed, that semester began on February 1, the very next day after my official date of retirement. The invitation stated that a requirement of this lectureship was that the lectures “had to be publishable.” It was that requirement which forced me to think well beyond my work in

Why Christianity Must Change or Die

and to begin to dream of what the Christianity of the future might look like. The Harvard lectures were destined to form the core of the book

A New Christianity for a New World,

which was published a year later. That book was not only my “second last book,” but it was also, along with my other work at Harvard, destined to form the first great opportunity in my “third half of life.”

The Harvard lectureship was later augmented by an invitation to teach two classes at the Harvard Divinity School and thus it served to focus anew my lifelong commitment to the vocation of teaching as the primary component of my ministry. Prior to my election as bishop, for many years in my parish ministry I had taught an adult class each Sunday morning before the worship service. That class had become the center around which my ministry was organized. While I was bishop, I followed a pattern of delivering twelve to fifteen public lectures a year within the diocese. I also accepted lecture invitations from outside my diocese in which I sought to relate biblical scholarship to scientific, economic and political concerns. I insisted on filtering the biblical stories through the crucible of contemporary knowledge, so making them pertinent to our day.

I also instituted in our diocese a sabbatical program consisting of a three-month study leave for every five years of service for our clergy. I used that time myself not only to set the example for our clergy about the importance of regular, disciplined study time, but also to immerse myself in contemporary biblical scholarship at such places as Union Theological Seminary in New York City, Yale Divinity School, Harvard Divinity School and the storied universities in Edinburgh, Oxford and Cambridge. With that study background and the publication of my books, the orbit of my influence began to extend beyond my diocese and my denomination. When I retired as bishop, to my great surprise the number of invitations I received to lecture literally exploded. Now that I finally had the time to be a full-time teacher I discovered that I would also have the opportunities. In the last five years I have delivered more than two hundred public lectures each year, the venues for which have moved, just as my books have moved, from the United States first to other English-speaking nations of the world and then ultimately to the nations of Europe, Asia and the South Pacific.

Lecturing and traveling are inevitably stretching experiences. Both stimulated my mind and that proved to be the catalyst for driving me back into a writing career that I assumed had been completed. It began in a very different and unexpected place when I was invited to become a columnist with an Internet start-up company called Beliefnet.com. In that capacity I not only filed columns on a regular basis, usually twice a month, but I was also given special assignments. For example, I covered and filed a daily report from the Democratic National Convention of 2000 that nominated the ticket of Al Gore and Joseph Lieberman. It was a great treat to end each day’s story with the sign-off words: “This is John Shelby Spong reporting to you live from the floor of the Democratic National Convention in Los Angeles!” I would have covered the Republican National Convention also, but a long-standing lecture commitment made that impossible. Gary Bauer was my substitute!

I was now beginning to experience life as a journalist. This was a world that I had barely known before and it forced me to realize that I had lived in a fairly narrow orbit inside the church. When Beliefnet.com went into bankruptcy, I trust not because I was writing for them, a new company called Agoramedia.com that grew out of Beliefnet was launched, and the people heading that new Internet venture invited me to become one of their weekly columnists. They began to market the column to subscribers late in 2002. I was now writing a column on religion, politics, social affairs, ethics and even economics each week. It was a struggle at first, both to get the column established in the public arena and to master the discipline of preparing a five-page essay every Friday, plus a question-and-answer feature to allow dialogue with my readers, for release the following Wednesday. These hurdles were, however, overcome and the column appears to be a growing success. Agoramedia changed its name to WaterfrontMedia.com and my column now has a core of regular readers that grows by several hundred subscriptions a month. WaterfrontMedia traced one column I wrote as an open letter to political columnist George Will after he had attacked my church in general and me in particular over our stand in favor of the full inclusion of gay and lesbian people. That exercise discovered that this column had been opened over one hundred thousand times, which confirmed its growing influence.

Journalistic writing is not like authoring a book. It is hot, reactive, contemporary and quickly dated. Books probe deeper and tend to last longer. Because both my career and my audience seemed to be expanding in retirement rather than contracting, the people at HarperCollins suggested that I consider resuming my book-writing career. It was Mark Tauber, now my HarperSanFrancisco publisher, who first suggested that I might create a book examining the hurtful texts of the Bible; that is, those texts that have been used through history to justify the denigration or persecution of others, all the while carrying with them the implied and imposed authority of the claim that they were the “Word of God.” Mark especially urged me to examine and challenge the texts that Christians of a conservative bent were regularly using to keep their homophobia intact, since that was the major debate going on in Christian churches all over the world.

I was not enthusiastic about this task at first. I had moved beyond that debate and considered it to be essentially over. I do not mean that all prejudice against homosexual persons is over, but the back of this prejudice has been broken in both church and society and no one doubts the final outcome. To me such a book was fighting yesterday’s war. But then the project expanded and my eagerness to engage the task grew. There was also the history of the church’s anti-Semitism to explore. It is still alive and well in the Middle East and around the world today and the Bible is regularly used to undergird it. The comment attributed to Pope John Paul II, “It is as it was!” upon viewing Mel Gibson’s anti-Semitic motion picture

The Passion of the Christ

only reveals how deep and systemic that prejudice really is.

In addition to homosexuality and anti-Semitism, there was the way women have been treated in Christian history. The two largest Christian churches in the world, the Roman Catholics and the Orthodox tradition, still refuse to ordain women and the conservative Protestant churches continue to argue about something they call “headship,” which means that no woman should be allowed authority over a man. After this, other themes began to occure to me with some regularity. There was the issue of child abuse in the Western world that has operated under the rubric of “proper discipline,” which constituted another offense historically rooted in biblical quotations. There was that enormous religious negativity that attacks family planning and the subsequent environmental impact of overpopulation, all the while rooting itself in biblical authority in order to give its negativity credibility. Christian voices in our world continue to employ words that reveal nothing less than arrogance toward other religions, whose adherents they regard as fit subjects not for dialogue but for conversion. This attitude is regularly enforced with biblical claims that a particular religious tradition possesses the certainty of the ultimate truth of God that is seen first as religious bigotry and later as religious persecution. So the idea of doing a book to expose and challenge what I began to call first the “terrible texts of the Bible” and later “the sins of scripture” grew in its appeal. My purpose was to lay bare the evil done by these texts in the name of God.

Even that, however, was not enough to convince me to undertake the discipline required to write another book. As a committed Christian who has spent a lifetime studying the Bible and whose life has been deeply shaped by that study, I was not interested in writing what was beginning to sound like a negative, Bible-bashing book. I have passed the point in life when I find fulfillment in doing deconstruction. There had to be more to it than that. Exposing the misuse of scripture can, I believe, be done only in the context of introducing people to a proper way to engage this holy book of the Judeo-Christian tradition. So I began to research the “terrible texts of the Bible,” not just to lay bare the negativity, but with the hope of recovering that ultimate depth of the texts which I believe enables me to acknowledge the divine image in the face of every person, to see the love of Christ for every person and to assist in the call into life by the Spirit for every person. Only when the way to connect these positive ideas to an analysis of the “terrible texts of the Bible” became clear did this book finally take shape. It would be another, and I hope timely, attempt to rescue the Bible from those who first literalize it and then so badly misuse it.

As my lecturing career grew, it was inevitable that my study of these biblical ideas would begin to be incorporated into my lectures. That, of course, meant that audiences interacted with, questioned and challenged my thinking. This in turn brought refinement and more study. There were several venues that were particularly significant in developing the material for this book which I would like both to acknowledge and to thank. These include St. Deiniol’s Library in Hawarden, Wales, where the warden, Peter Francis, and his wife Helen run an incredibly open, groundbreaking conference center; the Lutheran Church in Finland, especially Lutheran pastors Hannu Saloranta and Jarmo Tarkki, as well as Bishop Wille Riekkinen and Heli Vaaranen, who served as my guides and translators while I was in that incredibly beautiful country; the Anglican Church in Montreal, Canada, especially the Reverend Canon Tim Smart, who invited me, and Archbishop Andrew Hutchinson and his wife Lois, who extended to Christine and me the gracious hospitality of their home and the more special gift of their friendship. I rejoice that the Canadian Anglican Church has since then made Archbishop Hutchinson their primate. Others include the Wilmot United Church of Canada in downtown Fredericton, New Brunswick, and the interim minister, Chris Levan, who invited me, and Peter Short, their permanent pastor, who was on leave from that church to serve as the moderator of the United Church of Canada; the First Methodist Church of Omaha, Nebraska, and its pastor Chad Anglemyer and lay leader Joan Byerhof, who organized my lectures there; the Asbury United Methodist Church of Phoenix, Arizona, and its pastor Jeff Proctor-Murphy, and the Via de Cristo Methodist Church in Scottdsdale, Arizona, and its pastor David Felten, who are two of the most gifted young clergy I have ever met; SPAFER (Southern Points Associations for Exploring Religion) in Birmingham, Alabama, and its founder Ken Forbes, who stirs the water in a constant battle against confining and prejudiced southern Christian fundamentalism; the people who call themselves the Gathering of Friends at Capital Manor Retirement Home in Salem, Oregon, and their leaders, Chuck Woodstock and Jack Powers, along with the Reverend Gail McDougle at the First Congregational Church in Salem and the Reverend Charles Wallace, the chaplain at Willamette University, who organized the series of lectures that I gave in Salem. This was the most energetic retirement community I have ever known. At Payap University in Chiang Mai, Thailand, I addressed a worldwide interfaith conference and had the privilege of being in dialogue with Muslims, Buddhists, Hindus and Jews, and at the Satya Wacana Christian University in Salatiga, Indonesia, President John Titaley invited me to address the students over two days on the subject of the Bible. Finally, when the book was finished but not yet published, I lectured on its specific content in Bay View, Michigan, where the Bay View Association led by R. Robert Kimes invited me to be their Chautauqua lecturer in the summer of 2004, and I also spoke on the book’s content in Houston, as the fall lecturer for the Foundation for Contemporary Theology, an opportunity that came in an invitation from Ruth Seliger. There were others, but these are the primary places in which the ideas of this book first began to see the light of day.