The Singularity Is Near: When Humans Transcend Biology (67 page)

Read The Singularity Is Near: When Humans Transcend Biology Online

Authors: Ray Kurzweil

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Fringe Science, #Retail, #Technology, #Amazon.com

Again, our engineering, even that of our vastly evolved future selves, will probably fall short of these maximums. In

chapter 2

I showed how we progressed from 10

−5

to 10

8

cps per thousand dollars during the twentieth century. Based on a continuation of the smooth, doubly exponential growth that we saw in the twentieth century, I projected that we would achieve about 10

60

cps per thousand dollars by 2100. If we estimate a modest trillion dollars devoted to computation, that’s a total of about 10

69

cps by the end of this century. This can be achieved with the matter and energy in our solar system.

To get to around 10

90

cps requires expanding through the rest of the universe.

Continuing the double-exponential growth curve shows that we can saturate the universe with our intelligence well before the end of the twenty-second century,

provided that

we are not limited by the speed of light. Even if the up-to-thirty additional powers of ten suggested by the holographic-universe theory are borne out, we still reach saturation by the end of the twenty-second century.

Again, if it is at all possible to circumvent the speed-of-light limitation, the vast intelligence we will have with solar system–scale intelligence will be able to design and implement the requisite engineering to do so. If I had to place a bet, I would put my money on the conjecture that circumventing the speed of light is possible and that we will be able to do this within the next couple of hundred years. But that is speculation on my part, as we do not yet understand these issues sufficiently to make a more definitive statement. If the speed of light is an immutable barrier, and no shortcuts through wormholes exist that can be exploited, it will take billions of years, not hundreds, to saturate the universe with our intelligence, and we will be limited to our light cone within the universe. In either event the exponential growth of computation will hit a wall during the twenty-second century. (But what a wall!)

This large difference in timespans—hundreds of years versus billions of years (to saturate the universe with our intelligence)—demonstrates why the issue of circumventing the speed of light will become so important. It will become a primary preoccupation of the vast intelligence of our civilization in the twenty-second century. That is why I believe that if wormholes or other circumventing means are feasible, we will be highly motivated to find and exploit them.

If it is possible to engineer new universes and establish contact with them, this would provide yet further means for an intelligent civilization to continue its expansion. Gardner’s view is that the influence of an intelligent civilization in creating a new universe lies in setting the physical laws and constants of the baby universe. But the vast intelligence of such a civilization may figure out ways to expand its own intelligence into a new universe more directly. The idea of spreading our intelligence beyond this universe is, of course, speculative, as none of the multiverse theories allows for communication from one universe to another, except for passing on basic laws and constants.

Even if we are limited to the one universe we already know about, saturating its matter and energy with intelligence is our ultimate fate. What kind of universe will that be? Well, just wait and see.

M

OLLY

2004:

So when the universe reaches Epoch Six [the stage at which the non-biological portion of our intelligence spreads through the universe], what’s it going to do?

C

HARLES

D

ARWIN

:

I’m not sure we can answer that. As you said, it’s like bacteria asking one another what humans will do

.

M

OLLY

2004:

So these Epoch Six entities will consider us biological humans to be like bacteria?

G

EORGE

2048:

That’s certainly not how I think of you

.

M

OLLY

2104:

George, you’re only Epoch Five, so I don’t think that answers the question

.

C

HARLES

:

Getting back to the bacteria, what they would say, if they could talk—

M

OLLY

2004:

—and think

.

C

HARLES

:

Yes, that, too. They would say that humans will do the same things as we bacteria do—namely, eat, avoid danger, and procreate

.

M

OLLY

2104:

Oh, but our procreation is so much more interesting

.

M

OLLY

2004:

Actually, Molly of the future, it’s our human pre-Singularity procreation that’s interesting. Your virtual procreation is, actually, a lot like that of the bacteria. Sex has nothing to do with it

.

M

OLLY

2104:

It’s true we’ve separated sexuality from reproduction, but that’s not exactly new to human civilization in 2004. And besides, unlike bacteria, we can change ourselves

.

M

OLLY

2004:

Actually, you’ve separated change and evolution from reproduction as well

.

M

OLLY

2104:

That was also essentially true in 2004

.

M

OLLY

2004:

Okay, okay. But about your list, Charles, we humans also do things like create art and music. That kind of separates us from other animals

.

G

EORGE

2048:

Indeed, Molly, that is fundamentally what the Singularity is about. The Singularity is the sweetest music, the deepest art, the most beautiful mathematics. . .

.

M

OLLY

2004:

I see, so the music and art of the Singularity will be to my era’s music and art as circa 2004 music and art are to . . .

N

ED

L

UDD

:

The music and art of bacteria

.

M

OLLY

2004:

Well, I’ve seen some artistic mold patterns

.

N

ED

:

Yes, but I’m sure you didn’t revere them

.

M

OLLY

2004:

No, actually, I wiped them away

.

N

ED

:

Okay, my point then

.

M

OLLY

2004:

I’m still trying to envision what the universe will be doing in Epoch Six

.

T

IMOTHY

L

EARY

:

The universe will be flying like a bird

.

M

OLLY

2004:

But what is it flying in? I mean it’s everything

.

T

IMOTHY

:

That’s like asking, What is the sound of one hand clapping?

M

OLLY

2004:

Hmmm, so the Singularity is what the Zen masters had in mind all along

.

CHAPTER SEVEN

Ich bin ein Singularitarian

The most common of all follies is to believe passionately in the palpably not true.

—H. L. M

ENCKEN

Philosophies of life rooted in centuries-old traditions contain much wisdom concerning personal, organizational, and social living. Many of us also find shortcomings in those traditions. How could they not reach some mistaken conclusions when they arose in pre-scientific times? At the same time, ancient philosophies of life have little or nothing to say about fundamental issues confronting us as advanced technologies begin to enable us to change our identity as individuals and as humans and as economic, cultural, and political forces change global relationships.

—M

AX

M

ORE

, “P

RINCIPLES OF

E

XTROPY

”

The world does not need another totalistic dogma.

—M

AX

M

ORE

, “P

RINCIPLES OF

E

XTROPY

”

Yes, we have a soul. But it’s made of lots of tiny robots.

—G

IULIO

G

IORELLI

Substrate is morally irrelevant, assuming it doesn’t affect functionality or consciousness. It doesn’t matter, from a moral point of view, whether somebody runs on silicon or biological neurons (just as it doesn’t matter whether you have dark or pale skin). On the same grounds, that we reject racism and speciesism, we should also reject carbon-chauvinism, or

bioism

.

—N

ICK

B

OSTROM

, “E

THICS FOR

I

NTELLIGENT

M

ACHINES:

A P

ROPOSAL, 2001

”

Philosophers have long noted that their children were born into a more complex world than that of their ancestors. This early and perhaps even

unconscious recognition of accelerating change may have been the catalyst for much of the utopian, apocalyptic, and millennialist thinking in our Western tradition. But the modern difference is that now

everyone

notices the pace of progress on some level, not simply the visionaries.

—J

OHN

S

MART

A

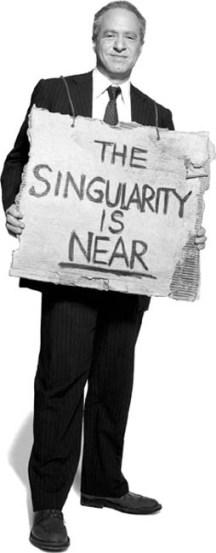

Singularitarian is someone who understands the Singularity and has reflected on its meaning for his or her own life.

I have been engaged in such reflection for several decades. Needless to say, it’s not a process that one can ever complete. I started pondering the relationship of our thinking to our computational technology as a teenager in the 1960s. In the 1970s I began to study the acceleration of technology, and I wrote my first book on the subject in the late 1980s. So I’ve had time to contemplate the impact on society—and on myself—of the overlapping transformations now under way.

George Gilder has described my scientific and philosophical views as “a substitute vision for those who have lost faith in the traditional object of religious belief.”

1

Gilder’s statement is understandable, as there are at least apparent similarities between anticipation of the Singularity and anticipation of the transformations articulated by traditional religions.

But I did not come to my perspective as a result of searching for an alternative to customary faith. The origin of my quest to understand technology trends was practical: an attempt to time my inventions and to make optimal tactical decisions in launching technology enterprises. Over time this modeling of technology took on a life of its own and led me to formulate a theory of technology evolution. It was not a huge leap from there to reflect on the impact of these crucial changes on social and cultural institutions and on my own life. So, while being a Singularitarian is not a matter of faith but one of understanding, pondering the scientific trends I’ve discussed in this book inescapably engenders new perspectives on the issues that traditional religions have attempted to address: the nature of mortality and immortality, the purpose of our lives, and intelligence in the universe.

Being a Singularitarian has often been an alienating and lonely experience for me because most people I encounter do not share my outlook. Most “big thinkers” are totally unaware of this big thought. In a myriad of statements and comments people typically evidence the common wisdom that human life is short, that our physical and intellectual reach is limited, and that nothing fundamental will change in our lifetimes. I expect this narrow view to change as

the implications of accelerating change become increasingly apparent, but having more people with whom to share my outlook is a major reason that I wrote this book.