The Silk Road: A New History (28 page)

Read The Silk Road: A New History Online

Authors: Valerie Hansen

Yet these tombs retain distinctly Sogdian elements. In place of Chinese coffins, the Sogdian tombs contain either a stone bedlike platform or a miniature stone house. In some cases the remains of the dead were placed on the platform or inside the house, but in others—most notably that of An Jia—they were not.

5

Like ossuaries, the stone houses are decorated on the outside; in contrast, the stone beds have partitions with decorations facing in, as if an ossuary has been “turned inside out.”

6

Unlike ossuaries, the stone beds show scenes from the life of the deceased, never the subject of traditional Sogdian ossuary art. The extremely realistic scenes clearly draw on the life experiences of the deceased; they may depict this world or possibly the next.

Named one of the top ten archeological discoveries of 2001, the tomb of An Jia is the only tomb of a Sogdian that had not been previously disturbed when archeologists uncovered it. The vast majority of tombs in China have been opened previously, often multiple times, by grave robbers. An Jia’s tomb had a sloping walkway 9 yards (8.1 m) long leading to a door (see color plate 15).

Outside the door was an epitaph for the deceased. Typical of Chinese epitaphs, the text was carved on a low, square base and then covered with a lid, both made of stone. According to Chinese burial practices, An Jia’s remains should have been placed in a coffin that rested on top of this stone bed. But the bones were scattered outside the tomb door on the ground, not on the stone bed inside where the Chinese would have placed them—a practice that has defied all explanation, since neither Zoroastrian nor Confucian custom sanctioned such a burial. Everything near the epitaph, including the walls, had smoke marks, as if a fire had occurred at some point.

7

An Jia, his epitaph reports, was descended from a Sogdian family from Bukhara (in modern Uzbekistan) who had migrated to Liangzhou, what is now Wuwei, the important Gansu town on the road between Chang’an and Dunhuang where Xuanzang also stopped.

8

An Jia was born in 537 to a Sogdian father and probably a Chinese mother from a local Wuwei family.

9

The epitaph claims that his father held two government positions, one in Sichuan, but this seems unlikely given the distance from Sichuan to Wuwei; much more likely, these were honorary positions granted to the father posthumously because of his son’s success.

10

An Jia was indeed successful. First serving as sabao in Tongzhou (modern-day Dali, Shaanxi, north of Xi’an), he was given the highest rank a sabao could achieve.

11

Starting in the Northern Wei dynasty (386–534) dynasties in central China began to appoint headmen for the Sogdian communities, and they adopted the originally foreign word for the position in the Chinese bureaucracy. As a result, sabao took on a new meaning: an official appointed by the Chinese to administer the residents of a foreign community. An Jia received such an appointment under the Northern Zhou, the dynasty in power in Chang’an before his death at the age of sixty-two in 579. An Jia’s tomb combines Chinese and Sogdian motifs. The painting above the door shows a Zoroastrian fire altar on a table borne by three camels, an attribute of the Sogdian God of Victory.

12

The funeral chamber measured 12 feet (3.66 m) square, 10.83 feet (3.3 m) tall, and held the stone funeral platform with stone panels on the sides and along the back. The craftsmen who made them first carved shallow reliefs into the stone and then painted the figures, buildings, and trees with red, black, and white pigments and filled in the background with gold paint. There are twelve scenes in all (three each on the left and right sides, six at the back).

13

On the center of the back wall, a plump An Jia appears seated next to a woman, probably his wife, wearing Chinese clothes in a Chinese-style building with a bridge in front. The Sogdian funeral beds and houses found in China almost always depict the Sogdian swirl, a dance performed by both men and women at parties. An Jia’s funeral bed depicts the dance three times (see color plate 14).

THE CHINESE TOMB OF A SOGDIAN HEADMAN

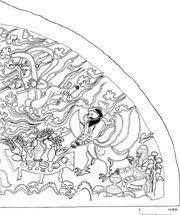

The lintel above the doorway to An Jia’s tomb skillfully integrates Chinese and Sogdian motifs. A priest-bird with a man’s head and torso but a bird’s legs and distinct claws stands upright. Wearing a padam face mask, he tends the table bearing bowls and vases with flowers. He represents the Zoroastrian god Srosh, associated with the rooster, who helps the soul cross the bridge from this world to the next and who also serves as a judge in the next world. Above the priest-bird floats a Chinese-style musician surrounded by clouds. The figure on the lower right, who wears a white cap and has a pronounced mustache, is the deceased sabao, An Jia, himself. Cultural Relics Publishing House.

The panels from An Jia’s tomb show little, if any, mercantile activity. Camels bearing goods appear on one of the panels at the back, but the context seems more diplomatic than mercantile. On the same panel, An Jia appears to be conversing with a Turkish leader in his tent.

14

If the camels are indeed carrying trade goods, then these are gifts to be exchanged following the completion of negotiations, a practice that accords with the envoy-dominated trade described in earlier chapters, most notably in the portrayal of emissaries and the gifts they bear in the Afrasiab palace of Samarkand.

A second Sogdian tomb, found 1.4 miles (2.2 km) east of An Jia’s tomb in 2003, offers fascinating parallels.

15

The deceased was named Wirkak, a Sogdian name derived from the word for “wolf,” and his Chinese family name was Shi; the space for his Chinese given name was left blank, so it is unknown. Like An Jia’s tomb, Wirkak’s tomb had a Chinese-style sloping walkway leading to the tomb chamber. Whereas An Jia had a stone bed, Wirkak had a stone house 8 feet (2.46 m) long, 5.1 feet (1.55 m) wide, and 5.18 feet (1.58 m) high with different scenes on the outside walls. Sand had filled the tomb, and archeologists found only this stone house, with a broken roof, inside. There were no other grave goods.

Shi Wirkak’s epitaph was in an unusual position above the door of the stone house. Even more unusual, his epitaph had two versions: one in Sogdian on the right, and one in Chinese on the left.

16

The two texts overlap in their account of the facts of Shi Wirkak’s life but are not translations of the same text. The scribe(s) who wrote the texts had a weak command of both languages. The two texts concur that Wirkak died in 579, the same year as his wife; had three sons; and served as a sabao in Wuwei, Gansu, where An Jia had also been a sabao. The Sogdian text concludes: “This tomb [i.e. god-house] made of stone was constructed by Vreshmanvandak, Zhematvandak, and Protvantak [or Parotvandak] for the sake of their father and mother in the suitable place,” an indication that the term “god-house” must have referred to the house-shaped sarcophagus placed in the tomb.

17

The stone house had a roof and a base, and the front had two doors and two windows. Bird-priests, similar to those above the door of An Jia’s tomb, tend fires beneath the windows, and many elements on the stone house deeply resemble motifs from the An Jia tomb: a banquet, hunting scenes, the deceased inside a tent talking with someone of a different ethnicity. Some of the images are downright puzzling: who, for example, is the ascetic in the cave on the left edge of the northern side? Laozi? A Brahman? Given the openness of the Sogdians to deities from other religious systems, they may never be identified.

The eastern side of the stone house portrays the progress of the soul of the deceased over the Chinwad Bridge. This arresting scene is much more detailed than any portrayal of Zoroastrian beliefs about the fate of the dead from either Sogdiana or the heartland of Zoroastrianism in Iran.

Every motif—the winged, crowned horses, the winged musicians, the crowned human figures with streamers flying behind (a time-honored way of portraying monarchs in Iranian art)—suggests that Wirkak and his wife are about to enter paradise. The identification of the different elements in this scene rests on parallels between the carvings on the stone sarcophagus and Zoroastrian texts, preserved in their ninth-century versions, indicating close familiarity with these religious texts among Sogdians resident in China in the late sixth century—an important finding, since no Zoroastrian texts have surfaced in China to date.

18

Both An Jia and Shi Wirkak died in 579, in the closing years of the Northern Zhou dynasty, a time of rapid political change. The ruler of the Northern Zhou arranged for his heir to marry the daughter of one of his generals in 578. That heir succeeded to the throne in 581 but died soon after, leaving a boy on the throne. At first, the boy’s maternal grandfather assumed the position of regent, but in the same year he seized power and founded the Sui dynasty. For the next eight years his armies campaigned all over China, gradually gaining territory, until in 589 he reunified the empire.

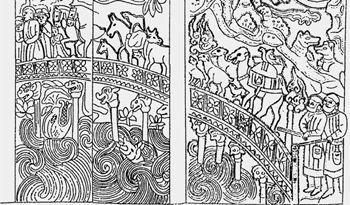

THE PERILOUS CROSSING TO THE NEXT WORLD

This scene comes from a stone house buried in the tomb of Shi Wirkak. On the lower right, two human Zoroastrian priests wearing padam face masks stand facing a bridge. There they conduct the ceremony that sends the souls of the dead off to the next world. On the left, Wirkak and his wife lead a procession including two children (did they predecease their parents?), animals, two horses, and a camel bearing goods across the bridge. Significantly, Wirkak and his wife have made it safely past the monster with ominously bared teeth waiting in the water below. According to Zoroastrian teachings, only those who have told the truth and behaved righteously can cross to the other side of the bridge unharmed; those who have not plunge to their death below as the bridge narrows to razor-width. Courtesy of Yang Junkai.

The original capital of the Sui dynasty lay in Yangzhou, near the coast of central China, but in 582 the Sui founder relocated his capital to Chang’an, the capital of many earlier and powerful dynasties. He built an entirely new and formally planned city on a site south and east of the city’s capital during the Northern Zhou (which was located on the same site as the Han-dynasty capital). The Sui founder ruled for nearly thirty years before dying a natural death in 604. His son succeeded him and led his armies on a series of military campaigns in Korea, which he never succeeded in conquering. The Chinese suffered massive losses, prompting a general to overthrow the emperor and establish the Tang dynasty in 618.

19

Under the Tang, the capital remained at Chang’an except for brief intervals.

When the new city was completed, its 5 yard (4.6 m) high walls ran 5.92 miles (9.5 km) east to west and 5.27 miles (8.4 km) north to south, enclosing a rectangular area of some 31 square miles (80 sq km). Broad main avenues divided the city; the widest was 500 feet (155 m) across, the equivalent of a forty-five-lane highway.

20

The city had 109 districts, called quarters (

fang

). Each quarter had a wall around it; city officials closed the gates every night to enforce a strict curfew. To the north of the city, outside the rectangle, were the palace and various government offices, both civil and military. Only officials and members of the royal family could enter that district. Officials and courtiers tended to live in the eastern half of the city. Because they could afford more spacious houses with gardens, the eastern half of the city was less densely populated. Most ordinary people lived in the western half.

Two markets, known as the Eastern and Western Markets, each occupied an area about 0.4 square miles (1 sq km).

21

A road 400 feet (120 m) wide ran along the outside edge of the market to allow passage of people and vehicles; inside the market were more streets. Both markets, like the quarters of the city, were walled, and the gates were carefully guarded. No officials above the fifth rank (out of a total of nine) were allowed to enter, because the officials who served under Emperor Taizong (reigned 627–49) and who compiled the Tang Code, viewed commerce as polluting. The Tang Code made an exception for market officials, whom it charged with checking weights and setting prices every ten days.

22

Market supervisors issued certificates of ownership to the purchasers of livestock and slaves, who had to present these each time they crossed the border. These officials made sure that the markets opened only at noon and closed two hours before sundown.

23