The Silk Road: A New History (22 page)

Read The Silk Road: A New History Online

Authors: Valerie Hansen

All beings of Light, the righteous [elect] and the auditors, who have endured much suffering, will rejoice with the Father.…

For they have fought together with Him, and they have overcome and vanquished that Dark One who had boasted in vain.

94

Hymns like this have permitted scholars to reconstruct the major tenets of Manichaeism, which would otherwise be unknown, since so few Manichaean texts exist anywhere in the world.

Some of the texts Le Coq found were beautifully illustrated but so severely damaged by water that all the pages stuck together and could not be separated. One such fragment survives in the Museum of Indian Art in Berlin, which holds all the material brought back by the four German expeditions that survived the bombing during World War II. This miniature depicts the Bema festival, the most important holiday of the Manichaean year, in which the clergy, or elect, sang hymns, read aloud Mani’s teachings, and ate a meal, shown in color plate 11A.

95

Although Manichaeism was the official state religion of the Uighur Kaghanate, little Manichaean art survives onsite at Turfan. Only one cave painting at Bezeklik, all scholars concur, is definitely Manichaean.

96

The mural has suffered great damage since 1931 when the copy shown on

page 109

was made, and those managing the site rarely show it to visitors.

Why does so little Manichaean art survive at Turfan and the surrounding cave sites? Sometime around the year 1000 the rulers of the Uighur Kaghanate chose to patronize Buddhism and not Manichaeism.

97

Several surviving caves in Turfan, including cave 38 at Bezeklik, bear witness to this shift: close examination of the cave walls shows that the caves had two layers, often a Manichaean layer (not always visible) lies beneath a Buddhist layer. The Uighur court’s decision to support Buddhism apparently ushered in a new era in which only one religion was tolerated.

In 1209 the Mongols defeated the Uighur Kaghanate of Turfan but left the Uighur kings in place. In 1275 the Uighurs sided with Khubilai Khan. When defeated by one of his rivals, the Uighur royal family fled and settled in Gansu in 1283. Although peasant rebels overthrew the Mongol rulers of China and established the Ming dynasty in the fourteenth century, Turfan remained outside of the borders of China and under the rule of the united Mongols and, later, the Chaghatai branch of the Mongols. In 1383 Xidir (Xizir) Khoja (reigned 1389–99), himself a Muslim, conquered Turfan and forced the inhabitants to convert to Islam, the prevailing religion of the region today.

98

The region remained independent of China until 1756, when the Qing dynasty armies invaded.

99

The history of Turfan falls into three distinct periods: before the Tang conquest of 640, Tang rule (640–755), and after 803, when the Uighur Kaghanate was based in the oasis. In the periods both before and after Chinese rule, the economy was largely self-sufficient. Most of the documented movement along the overland routes was either by envoys or refugees. The high point of the Silk Road trade coincided with (because it was caused by) the presence of the Chinese troops. The Tang government injected vast amounts of both cloth and coin into the local economy, which resulted in high interest rates on loans even for poor farmers. But when the Chinese forces withdrew after 755 the local economy reverted to a subsistence basis. As coming chapters will show, much information about the spending patterns of the Tang government survives in other oases (particularly Dunhuang), but the overall pattern is clear. The Silk Road trade was largely the byproduct of Chinese government spending—not long-distance commerce conducted by private merchants, as is so often thought.

A LETTER TO SAMARKAND

One of eight folded pieces of paper from an abandoned mailbag, this letter was written on a sheet of paper and then folded into a small silk bag and labeled “Bound for Samarkand.” These letters, dating to 313 or 314, are among the most important surviving documents about the Silk Road trade, because they are written by private individuals, including businessmen, and not by government officials. Courtesy of the Board of the British Library.

CHAPTER 4

Homeland of the Sogdians,

the Silk Road Traders

Samarkand and Sogdiana

I

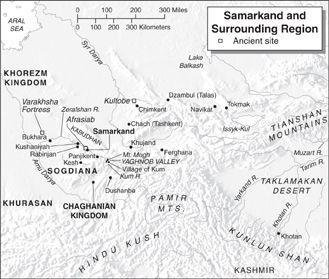

n 630, when the Chinese monk Xuanzang left Turfan, he took the most traveled route west. After stopping in Kucha, he crossed the Tianshan Mountains, visited the kaghan of the Western Turks on the northwestern edge of Lake Issykkul in what is now Kyrgyzstan, and then proceeded to Samarkand in modern Uzbekistan. From Samarkand, travelers could go west to Syria, return to the oasis states of the Taklamakan, or proceed south to India, as Xuanzang did. Samarkand was then the major city of the Sogdians, the Iranian people who played such an important role in the Silk Road trade and who formed China’s largest and most influential immigrant community during the Tang dynasty.

1

The Sogdians spoke a Middle Iranian language called Sogdian, a descendant of which is still spoken in the remote Yaghnob Valley in nearby Tajikistan (see the document on the facing page in Sogdian).

In Samarkand, Xuanzang entered the cultural sphere of the Iranians, whose languages, religious practices, and customs, although equally old and equally sophisticated, differed profoundly from those of the Chinese. The modern traveler following in Xuanzang’s steps crosses a different kind of border, just as distinct, between China and the former Soviet Union. Jokingly referred to as the “Steel Road” by Chinese, this treacherous highway is strewn with overturned trucks and metal debris from dismantled Soviet-era factories being carted off to China.

The seventh-century route posed real dangers. After waiting two months for the snow to melt, Xuanzang left Kucha and headed toward the Tianshan Mountains. Provided with camels, horses, and guards by the Kucha king, Xuanzang traveled only two days before encountering more than two thousand Turk (Tujue) robbers on horseback. They did not rob Xuanzang, his disciple and biographer Huili explains, since they were too busy dividing previously looted goods among themselves.

The travelers then reached the towering Tianshan Mountains, where Mount Ling made a profound impression on Xuanzang:

The mountain is dangerous and precipitous, so steep that it rises up to the sky. Since the road was first opened, the icy snow accumulates in places where it remains frozen, not melting in either the spring or summer. Huge expanses of ice meet and join the clouds. The snow is so blindingly white that one cannot see where it ends and the clouds begin. The icy pinnacles fall and lie across the road. Some are a hundred feet high, some several cubits [

zhang,

roughly 10 feet, or 3 m] across.

The trip was extremely arduous, Huili continues:

It is difficult to proceed on the rough, narrow paths. Add the snowy wind flying in different directions, and even fur-lined garments and boots cannot prevent a battle with the chill. Whenever one wants to sleep or eat, there is never a dry place to stop, so the only thing to do is to hang up a cauldron and cook, and to lay one’s mat out on the ice and sleep.

After seven days the survivors in Xuanzang’s group finally left the mountains. Three or four out of every ten people in the group had died from hunger or cold, and the losses among the horses and cattle were even greater.

2

These fatalities were unusually high, prompting some to wonder whether Xuanzang and his companions were caught in an avalanche unmentioned by his biographer.

3

Due to the extraordinarily dry climate, ice formed only at the mountaintops of the Tianshan Mountains, far above the timberline, with the result that a band of dirt and sand lay immediately below the ice. When chunks of ice broke off, they hurtled down dirt, not ice, creating truly terrifying avalanches. Avalanche or not, this was certainly the most perilous crossing of Xuanzang’s entire trip to India.

4

After crossing the Tianshan Mountains, Xuanzang and his companions arrived at Lake Issyk-kul in Kyrgyzstan. Issyk-kul means “hot lake” in Turkic, and the sea is fed by warm springs that prevent it from freezing over. The Chinese also called Issyk-kul the “warm sea.”

5

Near the modern town of Tokmak, at a site called Ak-Beshim, near the lake’s western edge, Xuanzang met the leader of the Western Turks, the kaghan, who wore a fine green silk robe and wrapped a ten-foot-long silk band around his head, allowing his long hair to fall down his back.

6

At the time, in 630, the kaghan headed a confederation of Turks that controlled the territory all the way from Turfan to Persia. He did not rule directly but left local rulers, like those in Turfan, Kucha, and Samarkand, in place as long as they paid him tribute, provided troops when requested, and obeyed his commands. For several days the kaghan, like the Gaochang king, tried to persuade Xuanzang to stay at Tokmak and not go on to India. When Xuanzang did not consent, the kaghan finally gave in and provided the monk with an interpreter, fifty pieces of silk for travel expenses, and letters of introduction to the various rulers who accepted him as their overlord. From the town of Tokmak, Xuanzang and his party traveled westward, going through lovely mountain pastures, and then across the barren Kizil Kum desert before reaching Samarkand.

In his

Record of Travels to the West,

a detailed account of the different countries of the Western Regions, Xuanzang sketched the basic traits of the Sogdians.

7

They did not write characters; instead they used an alphabet of some twenty letters in various combinations to record a broad vocabulary. Their clothing was simple, made of fur and felt, and, like the Turkish kaghan, the men bound their heads with cloth and shaved their foreheads. This struck Chinese observers as unusual, because they viewed hair as an integral part of the body, a gift from one’s parents that should not be cut.

Xuanzang gives voice to a widely held Chinese view of the Sogdians: “Their customs are slippery and tricky, and they frequently cheat and deceive, greatly desiring wealth, and fathers and sons alike seek profit.”

8

The compilers of the official history of the Tang dynasty echoed this prejudice in their description of how the Sogdians raised their sons to be merchants: “When they give birth to a son, they put honey on his mouth and place glue in his palms so that when he grows up, he will speak sweet words and grasp coins in his hand as if they were glued there.… They are good at trading, love profit, and go abroad at the age of twenty. They are everywhere profit is to be found.”

9

Unfortunately, few Sogdian-language sources are available to correct these stereotypes. The climate in and around Samarkand is not as dry as that of the Taklamakan Desert, the soil is more acidic, and many materials were destroyed after the Islamic conquest of the early eighth century. Only two important groups of Sogdian-language documents survive: the first, the eight Sogdian “Ancient Letters” from the early fourth century, was found by Aurel Stein outside Dunhuang, while the second, nearly a hundred documents from a castle under siege, is from the early eighth century and was discovered in the 1930s outside Samarkand. Other Sogdian-language materials are limited to inscriptions on silver bowls or textiles, captions on paintings, and the many religious texts found at Turfan, which say little about the history of the Sogdians.

10