The Silent Boy (2 page)

Authors: Lois Lowry

I hoped that someone was building me a mazing for my birthday, but I didn't think that anyone was because there was no noise coming from the Bishops' barn or from our stable, except the plain old noise of the horses snorting and stamping their feet as Levi cleaned their stalls.

Our horses were named Jed and Dahlia, and they were brown but their manes and tails were black. Our cook was named Naomi, and she was also brown. Everything has a color, I remember thinking. I could not think of a single thing that had no color, except the water in my bath. You could see through water, I realizedâcould see your own hand when you tried to hold water in it, but then it ran away, right through your fingers, no matter how hard you tried to keep it there.

Austin had one more thing besides the mazing, onemorethingthatIwishedIhad.Hehadababy sister! She had horrid black hair and cried a lot and her name was Laura Paisley Bishop.

How they got Laura Paisley was very, very

interesting to me. Austin's Nana took him on the train to Philadelphia for a whole day. How I wished my grandmother would do that for me! My own Gram lived in Cincinnati and came by train in the summers to visit, but she never took me with her on the train. Austin said it was noisy and clattery and you could look through the windows and see trees go by as fast as anything. Sometimes, when the train was going around a curve, you could look ahead and see the engine and know that you were part of it, still attached. It was hard to imagine.

They rode to Philadelphia and went to a museum, where they saw stuffed creatures, like bears, posing as if they were alive, and then they had lunch in a restaurant, with strawberry ice cream for dessert. Then they went back to the train station and came all the way home on the train again. When they arrived at our town, Austin's Nana used the telephone at the railroad station to call his home and see if anything exciting had happened while they were away.

"My goodness!" she said to Austin, then. "There will be quite a surprise at your house when we get there."

So they walked all the way home from the station, and when they got to Austin's house, he saw the surprise. It was a baby sister!

They had found her out in the garden. That's

what they told Austin: that his mother had gone outside to pick some tomatoes for lunch, and when she looked down, she saw a lovely baby girl there.

"Fibber!" I said to Austin.

I did not believe him because I had been playing in my own backyard almost all day, and never once heard a baby, and did not see Mrs. Bishop go out with her tomato basket at all. In fact, my mother had told me to play quietly because Mrs. Bishop had a headache and was lying down most of the day.

So I called Austin a fibber and he was angry and threw some dirt at me and said I could never hold his baby. But I asked my mother later and she said it was true that Mrs. Bishop had found the baby in the garden. Mother said that she hoped someday we would find one in ours.

So I decided I would look carefully each day. But it seemed a very strange thing, that babies appeared in gardens, because it might be raining. Or it might even be winter! I hoped that the babies were bundled up in thick blankets then!

I had to apologize to Austin for calling him a fibber. His big brother, Paul, was there when I did, and Paul laughed and said I shouldn't bother. Paul said I was the smartest child on the street. (It was not true, because I couldn't read yet, no matter how I tried.) But his mother, who was sitting in a rocking chair holding Laura Paisley, said,

"Shhhhh," so Paul shushed and went away and slammed the screen door behind him, which startled the baby, so that her eyes opened wide for a second and then closed again.

I hoped her hair would improve because it really was horrid to look at. It was exactly like Jed and Dahlia's manes.

Father took me with him to the country to get the new hired girl. It was a Sunday afternoon in late September; I had just started second grade, and I would very soon be eight. My teacher's name was Miss Dunbar, and I loved her desperately, but the stories that we read in the classroom, filled with children who were helpful and kind and had very nice clothes, didn't hold my interest. I wanted to know more about people who

needed

things. My mother, sympathetic with my impatience, had been reading books to me at home. I had loved listening to

Little Women

because of the missing

father, the shortness of money, and the death of Beth, which I felt quite certain Father could have prevented if he had only been called in soon enough.

As we jiggled along, Father and I, in the crisp blue afternoon, behind the horses, I read the names on the mailboxes.

"Look for

Stoltz,

" Father told me, and spelled it.

Butafterawhile,heandIbothlaughed.There were too many named Stoltz. A prosperous farm with a huge red barn and low white fencing around the cornfields had Stoltz on the mailbox; but so did another, closer to the road, that needed paint and a new roof.

"All cousins, I imagine," Father said. "The farm we want is up around the next bend, beyond that little grove of pine trees." He tapped the buggy whip gently on Jed's back so that the horses would continue along the dirt road. They slyly, lazily slowed their trot to a plod if we weren't paying attention.

I thought what it would be like to have cousins nearby. My own cousins lived in Cincinnati and I had never met them, only heard about them in letters that my mother read aloud. Maybe someday, Mother said, they could come to visit us by train.

But Peggy Stoltz, the girl we were coming to collect, had grown up here, where she could run through the pine grove and thenâI pictured her,

barefoot, in summer, with a dog scampering back and forth beside herâshe could spend the afternoon playing with her cousins, probably wading in the stream that Father and I had just crossed, the horses' hooves thumping on the bridge. Maybe they went fishing, or caught butterflies. Maybe they went into the hen house and slipped their hands under the fat, steamy bellies of hens to find the warm, hidden eggs.

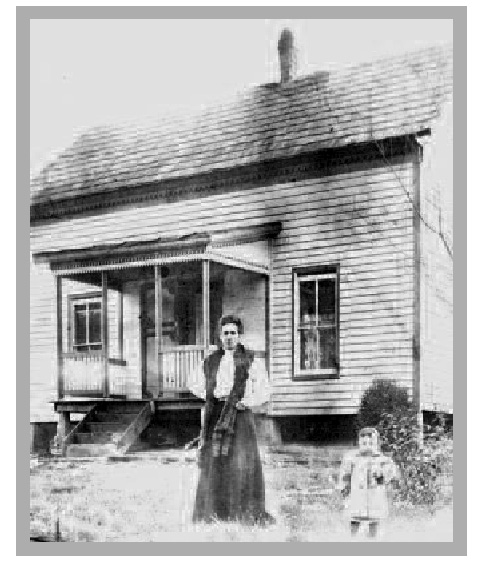

But when we rounded the bend and I saw Peggy Stoltz's home, I knew that her summers were not carefree ones. It was tidy but stark. It was poor.

It was why, at not quite fifteen years old, Peggy Stoltz was leaving school and becoming a hired girl. There was nothing for her here. My seven-year-old perception saw in an instant the contrast between our house and the one Peggy would be leaving.

The horses turned into the dooryard at Father's direction. Then they slowed, stopped, shook their heads, and snorted. "Mrs. Stoltz," Father said, and tipped his hat.

Peggy's mother had been standing in the yard, probably watching for our buggy. She smiled slightly and nodded. "Doctor Thatcher," she said in reply. Then she pointed with a smile to a toddler, made chubby with coat, standing wide-eyed beside her."This is the one that caused us such worry. Look at her now."

Father secured the reins, set the buggy whip upright in its slot, and climbed down. He lifted me to the ground and then he leaned down toward the small girl, buttoned into a thick coat, who was frowning suspiciously at both him and me.

"Anna, is it? Do I remember it correctly?" Father asked Mrs. Stoltz, as he stood, and I saw the little one look up curiously at the sound of her own name.

"She had diphtheria last winter," Father told me. "I spent some long nights at this farm. But look at her rosy cheeks now!"

"She's very well, and into no end of mischief," Mrs. Stoltz said. "We have you to thank. Not for the mischief, though," she added, smiling.

"This is Katy," my father said. He nodded toward me. I held out my hand the way I'd been taught, and she shook it.

"Come inside. our Peggy's just getting her things together. I can give you coffee, and milk for your girl."

But at that moment, Peggy Stoltz pushed open the screen door and appeared on the porch, holding a bag. "Thank you," Father said, "but we'll go on. It's four miles back, and if I let the horses rest they'll not want to start up again."

I knew it wasn't true. The horses were obedient and strong. But I could tell, also, that Father didn't want to go into the woman's house, to drink

her coffee, to prolong her goodbye to her daughter. He didn't want to shame or sadden her. He took the bag from Peggy and hoisted it into the back of the buggy next to the medical bag that he always carried there.

"She's a hard worker," her mother said, "and a good girl." She picked up Anna, and the toddler wrapped her legs around her mother's hip as if to ride.

"We'll be good to your daughter, Mrs. Stoltz," Father said, "and my wife will be grateful for her help."

Peggy hadn't said anything at all. She simply stood, like someone accustomed to waiting. She had, I thought, a pretty face, with cheeks as pink as her little sister's; you could see a strength in it, too, and that one day she would look like her mother, proud and loving. Her brown hair was pulled up and back but the breeze pulled it away and it flew in wisps around her face.

Father lifted me to the buggy seat and as he did, Peggy went to her mother and hugged her,wrapping her arms around the little one, too, who began to wail. "Want my Peg," the little girl cried, holding out her arms, but by then Father was helping Peggy up into the seat beside me. Mrs. Stoltz said, "Be sure to give Nellie our love." Then she hushed the little girl and turned away. At a window of the house, I saw a curtain move aside,

and a face appeared; then a hand, pressed against the glass. I thought Peggy ought to know. I nudged her and pointed to the window.

"That's Jacob," Peggy explained to me, the first words I heard her say. She waved to the face in the window, and after a moment the curtain dropped back and the boy disappeared behind it.

There was a Jacob in my school, a fourth-grader, and I wondered if it was the same boy. Farm children came into town for school, some of them, until they left to work the farms or, as Peggy, to hire out.

"How old is he? Does he go to school?" I asked, as the horses started up and Father clucked at them and turned them into the road. I felt shy with Peggy; she was new to me.

She shook her head. "Just turned thirteen," she said. "He don't go to school. He never could. He's touched."

Touched in the head,

she meant. I had heard the phrase before, had never known exactly what it meant, but it didn't feel polite to ask anything more. As we moved at a trot down the road and the Stoltz house disappeared behind us, I thought of the boy's face through the window, and the way he had slowly raised his hand to say goodbye to his big sister.

I liked Peggy, liked feeling her beside me as we jiggled together in the buggy behind the horses

eager for home and oats; she was solid and warm and she smelled good, like soap and garden earth. I saw her hands in her lap and could see that they were shaped and hardened by work. There was a new scratch, pink and ragged, across the back of her right hand, and I touched it, without thinking.

She smiled. "Kitten," she said. "It meant no harm."

Â

Many of the families in our neighborhood had hired girls. They came in from the farms, leaving their large families behind with one less mouth to feed, usually in fall after helping with the harvest. They moved into attic rooms, doing the housework and laundry, helping mothers with new babies. They were accustomed to cold bedrooms and hard work. Indoor plumbing was new to many of the hired girls.

Some of them didn't stay long. They met town boys and married, or saved their money for secretarial school and went off to better themselves.

Peggy's sister Nell lived next door, in the Bishops' attic. I saw her every day in the yard, hanging up the laundry to dry. She helped Mrs. Bishop take care of Laura Paisley, who was lively and curious and into everything, now that she was two. When I went to play with Austin, Nell pushed the mop through our toys, pretending she was

going to mop us up. She was strong and pretty, with a great halo of bright red hair, and Austin said she made them all laugh. But I heard Mrs. Bishop tell Mother that she was afraid Nell would leave them. She had just turned sixteen but she had ambitions, Mrs. Bishop said, as if

ambitions

meant measles, something we should try not to catch.

Peggy seemed quieter, more serious, and even her hair was a subdued brown, with none of the flamboyance of her sister's. Mother greeted her and showed her around the house; I followed behind, not wanting to be left out. I had already helped Mother tidy the little bedroom Peggy would have on the third floor, and I watched to see if she would appreciate the quilt I had chosen for her bed, a pink and white one that matched the colors in the flowered curtains. I could see that Peggy liked her room. Mother went downstairs, but I stayed and watched while she opened her bag and put her things away. She didn't have a lot. She hung two dresses in the old wardrobe and put a Bible and a hairbrush on the dresser.

"Look through the window," I told her. "See over there? The next house?"

She looked where I was pointing.

"That's the Bishops' house. And your sister's room is there, through the maple tree. When the leaves are gone you'll be able to see Nell's window."