The Siege of Vienna: The Last Great Trial Between Cross & Crescent (30 page)

Read The Siege of Vienna: The Last Great Trial Between Cross & Crescent Online

Authors: John Stoye

Tags: #History, #Middle East, #Turkey & Ottoman Empire

7

Warsaw, Dresden, Berlin

and Regensburg

I

Administrative preparations to receive foreign armies in Austria were no doubt essential. The first duty of the ministers at Passau, as they saw it, was nonetheless the exercise of diplomacy. These armies would only move if the princes of Europe were brought to decide that they consulted their own best interests by coming to the rescue of the Habsburg Emperor. Treaty obligations, appeals to Christian sentiment, an analysis of the military implications if Kara Mustafa permanently lodged an Ottoman garrison in the heart of Europe: these were the major instruments to be handled by Stratmann and Königsegg in their unaccustomed quarters, as they looked to the world beyond the confines of the Danube.

They relied above all on Sobieski, bound by treaty to wage an aggressive war against the Turks in the campaigning season of 1683, and to help in the defence of Vienna if an emergency occurred.

In Poland the French ambassador had been heavily defeated in the course of the Diet’s proceedings. He still hoped that three or four months would be needed to raise the taxes for a new army, quite apart from the time taken in raising and assembling the troops. In any case he believed that some of the Polish provinces, in meetings of their own ‘diets’, were about to mangle the recommendations of the national Diet.

1

Aristocratic assemblies, enjoying very extensive privileges, would always be unwilling to tax themselves or their tenantry for the sake of the state, and in particular (so he reported) the governors of Poznań, Vilna and Ruthenia continued in a mood of the utmost antagonism to their elected King. The ambassador admitted to Louis XIV that royal propaganda was active, and feared that too many of the smaller nobility were likely to listen to it, but he still pinned his faith to the slow

workings of a political system in which the powers of King, Diet and Senate were held in check by the semi-independent status of the provinces. Time, the essence of the problem when armies had to be raised in the seventeenth century, appeared to be on his side. Yet on some important points de Vitry proved wrong. The provincial assemblies began to meet in the middle of May, and a fortnight later the overwhelming majority had accepted the proposals of the King and the national Diet. The Habsburg subsidy was also beginning to flow, and the military units to take shape.

But the weeks were passing swiftly by and, as they passed, the likelihood of an advance by the Poles into Podolia or farther east faded away. Here Sobieski ran into difficulties. He had intended to use the Church’s money for the purpose of recruiting Cossacks. He greatly respected their military qualities, and wanted to coax them to attack the Crimean Tartars, those important auxiliaries of the Sultan. Innocent XI decided otherwise, and pressed for direct action against the Turks. He ordered Pallavicini, the nuncio, not to transfer any funds to the King unless the Cossacks were committed by the terms of their agreement to fight in Hungary; nor was he to do so before the Poles themselves actually began hostilities. Sobieski expressed immense annoyance at what seemed to him a fatuous denial of ready money, which in the end he secured by promising to get not less than 3,000 Cossacks into action in Hungary by mid-August.

2

In fact they never appeared, to his own bitter disappointment.

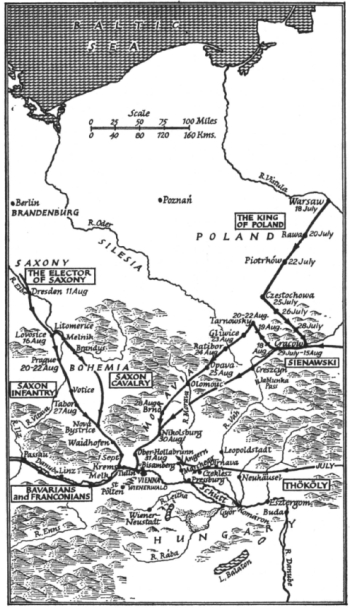

An aggressive Polish move in the south-east depended on the ‘old’ army of the standing troops. They were encamped under Field Hetman Sienawski within striking distance of Kamenets – which the Poles dearly wished to recapture. But in Warsaw it was reported, on 16 June, that the King himself proposed to move to Cracow at the end of the month, and had ordered Sienawski to withdraw from his advanced position and make Lvov his headquarters.

3

The shift of emphasis westwards occurred simply because the combined activity of Thököly and the Turks forced the Poles to mount guard along the Hungarian frontier. No one could be certain whether Kara Mustafa intended to halt at Györ, or march still farther up the Danube into Austria, or cross the Danube and threaten Moravia, Silesia and Poland. For the Poles, the very slow mobilisation of their ‘new’ forces increased the danger of the position. At the end of June Pallavicini almost felt tempted to hope for news of an immediate enemy attack in order to hasten the growth of the Polish army. Sobieski wrote a circular letter to all commanding officers to hurry them on, but clearly little or nothing had so far been done in many districts, above all in Lithuania. To this extent, de Vitry was right.

4

Meanwhile the Habsburg army under Lorraine had retreated from Neuhäusel. The Vienna government feared for the security of Moravia, and for the fate of its inadequate force in northern Hungary. It tried to increase the numbers under Schultz’s command by ordering Prince Lubomirski’s men to join him, and also the 4,000 troopers promised by Sobieski in April.

5

There was no sign

of the latter even towards the end of June, and urgent instructions reached Leopold’s envoy Zierowski at Warsaw to press hard for another reinforcement. In response, on 4 July the King agreed to move Sienawski and 7,000 men still farther west. They would come as far as Cracow,

6

unite with the new companies assembling there, and be prepared to defend the upper reaches of the Váh if this proved necessary. It was considered vital to be ready for action when the truce between Leopold and Thököly expired on 21 July.

On the day after Sobieski’s conference with Zierowski, unknown to them both, a messenger set out at top speed on the long journey from Vienna.

7

Count Thurn covered 350 miles in 11 days, and arrived at the royal residence of Wilanów outside Warsaw on 15 July. Austria was being invaded, its capital city was in danger, he reported, and the Emperor appealed to the King of Poland for help. In his turn the Count did not know that, while he spoke, Kara Mustafa was completing the encirclement of Vienna and Leopold was on his way from Linz to Passau.

At first Sobieski replied rather vaguely, promising assistance by the middle of August, if the Turks actually besieged Vienna. Much more detailed debate and discussion followed. Thurn gloomily told the nuncio that the facts were undoubtedly worse than anything contained in his dispatches, while the Poles had to weigh the view that the Sultan’s army was now committed to a risky enterprise in an area mercifully remote from most Polish territory. At length the King announced his decisions: to send Sienawski and his 7,000 men to join Lorraine; to prepare to go himself to Vienna if it was besieged by the Turks; and if it was not, to fight in Podolia or possibly Transylvania. But most important of all, he determined to leave Warsaw at once. He had been meaning to go, he had delayed and dithered, and now it abruptly became clear to him that delay was dangerous. Illness, hunting, the birth of a son, the Queen’s health, and purchases of property, had together taken up much of his time in the spring and early summer—the normal period of tranquillity between a winter of strenuous politics and a season of warfare in the late summer and the autumn. Now the sense of a gigantic emergency, and reasons of state, began increasingly to dominate his thinking again.

The King left Warsaw on 18 July and reached Cracow on the 29th.

8

The whole court with the Queen, Prince Jacob, the Austrian ambassadors, the papal nuncio, and an incalculable number of servants, carriages and carts went forward at an average speed of seventeen or eighteen miles a day. It was not fast going, nor was the road through Piotrków and Czestochowa the most direct to Cracow. But Sobieski had to allow sufficient time for the mobilisation of his army. He had to visit Our Lady of Czestochowa, then and now the greatest shrine in Poland, to beg her good offices for the coming campaign. He had to defer to his assertive wife, who wished to accompany him and to go to Czestochowa and Cracow.

At this point of time, when the fateful venture was just beginning to gather momentum, one circumstance strikes an observer very forcibly. No single

sensational report of a threatened catastrophe brought Sobieski to his feet, and made him ride from Warsaw to Vienna in order to honour his signature of a recent treaty. He was already preparing for the season’s campaigning, when Thurn arrived. Already he had been forced by stages to move troops away from the south-east, the theatre of all his earlier exploits against the Turks, to the south-west. At Wilanów on 15 July he first realised that the enemy was across the Rába in force, and concluded that Polish military power would have to be exerted somewhere in the triangle of ground between the points of Györ, Vienna and Cracow; but news of the Ottoman advance to Vienna, the city’s encirclement, and the state of siege involving the emergency clause in his treaty with Leopold, only reached him bit by bit. The distance from Warsaw to the Danube implied an equally disconcerting interval of time. Letters from Lorraine and Leopold to Sobieski were obsolete when they arrived, and his answers irrelevant. Then the gap narrowed. Vienna was ten days away at Warsaw, five at Cracow, and the news from Austria became clearer, fuller and more up to date. The King gradually elaborated in his mind a picture of the battlefield, drawn from the growing deposit of reports and dispatches which came in as he was riding south.

Piecemeal knowledge of the crisis hardly eased the strain which it imposed on the Poles. Their customary practice in the Turkish wars of the 1670’s had been the leisurely commencement in August or September of warfare which lasted until December, and was fought in Ruthenia, Podolia and the Ukraine with the manpower assembled there in the course of years. Men from the rest of Poland were moved south and east at a very slow pace, and the votes of a Diet to raise taxes and troops in one year often took effect in the next (or not at all). In any case an uneasy peace prevailed after 1676, and the Diet of 1677 insisted on a radical reduction of the army. In 1683 the machinery required for warfare on the grand scale was only just beginning to turn again, and no Polish politician would have been surprised if a serious attempt to recover Kamenets were delayed for twelve months. There was, of course, the unhappy possibility of a Turkish attack; but at least Poland had a military frontier in the southeast, with the ‘old’ army permanently stationed there. Yet now, as early as July, they had to visualise the immediate dispatch of an army to a point 200 miles beyond the south-western frontier of Poland. The decision to bring the ‘old’ troops to Cracow in fact signified that the ‘new’ regiments were not ready; and as Sobieski told Innocent XI in August, the authorities were only beginning to levy taxes for their pay.

9

The chronic shortage of Polish men and money certainly accounts for his very great preoccupation with foreign subsidies

10

and auxiliaries, but probably the worst feature of the crisis of 1683 was that it broke so early in the year. Nothing can have perplexed Sobieski more as he pondered affairs on his journey.

There is no sign that the King repented or was reluctant to push forward to Vienna, and without doubt it was the one course open to him. Not only did the treaty bind him, a treaty which accorded with his own judgment on the

strategic question, but the tremendous political struggle in the Polish Diet a few months earlier absolutely committed him to his present course of action. His party in Poland would have collapsed overnight if he had hesitated to support his allies at home and abroad on this issue.

On 19 July after the second day’s advance from Warsaw, Sobieski wrote to the Elector of Brandenburg in his secretary’s roundest Latin. ‘Already the Ottoman fury is raging everywhere, attacking alas! the Christian princes with fire and sword . . .’ Fresh news had come in, because he now referred to Leopold’s flight from the threatened city. He announced the speedy concentration of all Polish troops at Cracow, and summoned the Elector to send an expeditionary force instantly.

*

The request went off to Frederick William’s ambassador at Warsaw, but within twenty-four hours a special messenger followed with further news: a letter from Lorraine had just arrived.

11

This document, now lost, was the first instalment in a correspondence which has become one of the principal memorials of the time. Lorraine, it can be guessed, described how he was garrisoning Vienna with his infantry and placing his force of cavalry on the north bank of the Danube. A little later another letter reached the King. Its weightiest news was the withdrawal of the Habsburg troops under Schultz from the Váh valley.

12

Replying to Lorraine on 22 July,

13

the King recognises that ‘Vienna is really besieged by the Vezir’. Treaty obligations bound him to come to the rescue. He said that Vienna was more important to him than Cracow, Lvov and Warsaw—which meant, as always, that he preferred to defend these cities at the gates of Vienna. He was determined to overcome difficulties but complained that he had been left inexcusably ill-informed about conditions in Austria and Hungary. He asked for a detailed description of the Danube, its channels and islands; he obviously possessed no map of the Vienna landscape, nor did he even at this point specifically ask for one. He also criticised Lorraine for putting all his infantry into the city, thereby seriously weakening the army outside. He was all the more worried by this because his own infantry appeared dangerously inadequate. He hoped to use 4,000 Cossacks to cover the deficiency, and relied on the appearance of a strong Bavarian contingent of infantrymen. Further, he had not been told enough about the defences of the bridge or bridges which connected Vienna and its garrison with the field-army over the river. He recognised that the next bridge upstream, at Krems, might well prove of high military importance if Vienna were completely invested by the Turks, and Pressburg lost. But how strong, how large, was it? What was the character of the country

(‘qui monies, quae planities, quae flumina, qui passus’)

west of Vienna and south of the Danube?