The Siege of Vienna: The Last Great Trial Between Cross & Crescent (11 page)

Read The Siege of Vienna: The Last Great Trial Between Cross & Crescent Online

Authors: John Stoye

Tags: #History, #Middle East, #Turkey & Ottoman Empire

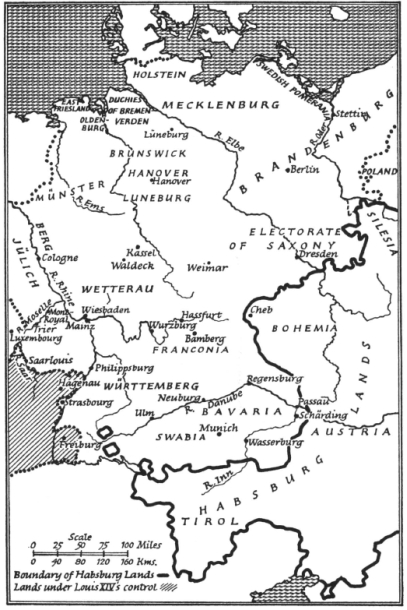

Germany in in 1679

The terms of the treaties of Nymegen were a triumph for Louis XIV. He took from Leopold Freiburg and the district of Breisgau east of the Rhine, while handing back to the Empire the demolished fortress of Philippsburg, some fifty miles farther north. All his claims on Alsace remained intact, he kept his hold on Lorraine and Franche Comté. Immediately afterwards he detached Frederick William of Brandenburg from the great alliance which had opposed him, and he retained old friends, Saxony and Bavaria. The ecclesiastical Electors of Trier, Mainz and Cologne, with the Elector Palatine, continued to take their cue from him. Nor was Louis helped only by the nervous calculations of these Rhineland princes. In broad stretches east of the river the population naturally desired to get rid of all the troops quartered on them during the war. Leopold had to withdraw regiments from Württemberg and Franconia.

1

When the Bishop of Münster offered to recruit for the Emperor, the Estates of the Wetterau and other districts north of the river Main formed a Union

*

to defend themselves, because the Bishop threatened to maintain on their territory the forces which he raised.

2

The dislike of smaller and unarmed states for the ‘armed’ principalities of the Empire was indeed one important

consequence of the recent war.

3

It made more difficult the task of setting on a sound basis the organisation of military forces strong enough to check the French monarchy.

It was soon clear that the German courts would have to reckon with an increase in Louis’ power over and above the gains scheduled in the peace treaties. First of all, his troops were slow to leave areas on the left bank of the Rhine where they had been stationed in the last stages of the war.

4

Then his tribunals at Metz, Besançon and Breisach began to issue judgments giving to the appellant (the King of France) whatever he claimed as his rights and sovereignties in the Empire. They automatically accepted his interpretation of the Westphalian and Nymegen treaties, and of all documents relevant to the old connection between fiefholders now subject to Louis and their feudal dependencies in the Empire. The latter were ‘reunited’ to France. The consolidation of French authority in the upper Moselle valley, and between the south bank of the Moselle and the west bank of the Rhine, swiftly entered a new and decisive phase in 1679 and 1680. Important new citadels were built at Saarlouis, Mont-Royal far down the Moselle, and at Fort Louis on the Rhine, facing Hagenau.

5

With the French already occupying Freiburg, across the river, no one could know where this advance by erosion would stop. When Strasbourg was occupied by force of arms, in September 1681, an Imperial City which the claim by ‘reunion’ could not remotely cover, the event simply confirmed much rumour and prophecy in the previous two years.

Louis XIV also threatened, less tangibly, Leopold’s constitutional authority in the Empire. Leopold at last had an heir, Joseph, who was born in 1678; but Louis’ secret agreements with some of the German Electors included a clause binding them to vote for him, or for a candidate named by him, in a future election to the title of King of the Romans—and the King of the Romans automatically succeeded the reigning Emperor. It was argued at the time, it has been argued since, that the French ministers never seriously intended to use such promises as more than a useful bargaining point.

6

But rumour about this aspect of their diplomacy was a reasonable cause for alarm at Vienna, and all Louis’ manoeuvres farther afield in Poland, Hungary, Transylvania or at Istanbul could be interpreted as means to a greater end: the Imperial crown itself.

There was equal uncertainty about the future of the Spanish empire. Franche Comté had fallen to France in 1678, apparently for ever. Austrian statesmen began to worry about Milan. In Flanders, the terms of peace by no means settled the territorial question. They left the King of Spain ‘free’ to choose between ‘alternative’ sacrifices of various towns and strips of countryside, the details of which were to be agreed after further negotiation: an easy and calculated opening for Louis, in the next round of discussions, to make further demands. Leopold, who never lost sight of his reversionary claims in this part of the world, could not disregard these difficulties in Flanders. If he did, momentarily distracted by the crises elsewhere, the Spanish

interest at his court was quick to correct him. It was supported by the Dutch envoy, and by all those statesmen who had learnt from bitter experience during the past decade how closely the affairs of the old ‘Burgundian Circle’ were still linked to the Empire. In any case reliance on Spanish subsidies, with little justification, still featured with curious prominence in diplomacy at this period. Their importance was overestimated whenever alliances against France were discussed, at Vienna or elsewhere.

The Habsburg court therefore felt bound to try and recover from a defeat which threatened even more serious consequences. The decision to join the Dutch a few years earlier had been a very difficult one, causing the downfall of the most important politician in Vienna, Zdenko Lobkowitz, who opposed it. Those who first determined on resistance to France, like Hocher, Schwarzenberg, Königsegg, still surrounded Leopold. If they retreated in 1678 and 1679, neither they nor Leopold were prepared to surrender. But this resolute bias against Louis XIV involved them in problems of the utmost complexity.

One decision, not to disband all the troops in Habsburg pay, was at least simple enough in theory. They were brought back into the hereditary lands, and with them came the men originally raised by the Dukes of Lorraine during their own struggle against the French.

7

Some of the best regiments to survive partial disbandment were stationed in south Germany, and kept watch over Louis’ advanced position at Freiburg. Even so, it remained difficult to pay and quarter them indefinitely; and the area farther north was still unguarded. Another decision, to try to reknit the alliance with the Dutch, also looked straightforward but the Dutch government was hardly in a mood to respond.

8

Encouraged by the French ambassador at The Hague, the peace party in Holland checked its opponents William of Orange and Waldeck. The Habsburg envoy here made no headway between January 1680, and the autumn of 1681.

The worst complications were in the Empire itself, dependent on the intricacy of the Imperial constitution, and the labyrinth of interests connecting princely families, cities and governments. The statesmen in Vienna had to pay close attention to a very large number of these separate courts: to the Electors of Brandenburg, Saxony and Bavaria at Berlin, Dresden and Munich; to the four Rhenish Electors, and to the more important princes of lesser rank like the three Brunswick rulers of Hanover, Celle and Wolfenbüttel, or to the ambitious Bishop of Würzburg and Bamberg, who all disposed of significant bodies of troops. They had to instruct the Emperor’s representatives at the Regensburg Diet itself, where envoys from the Estates of the whole Empire—in spite of many absentees—sat in permanent session, and the formal decisions of this great body politic were taken. They had to keep an eye on such centres as Ulm and Wiesbaden and Wasserburg, as well as on the more prominent capitals already mentioned, wherever members of different Circles, the

Reichskreise

, were accustomed to confer. A few of these loose historic

groupings of states within the Empire, at least in Franconia and Swabia, had functioned with increasing vitality since 1648;

9

they were concerned first of all with such things as currency, police and Imperial taxation, but could not evade the problems of defence and the quartering of troops, which were bound up with taxation. Nor could the Emperor’s statesmen safely neglect the larger Imperial Cities, like Frankfurt and Hamburg, which normally looked to him for support. And everywhere the Hofburg’s envoys criss-crossed with other envoys from the German states, or from Holland and Sweden and Denmark. Everywhere they encountered Louis XIV’s allies and emissaries, who were competently directed, on the watch to emphasise that Habsburg influence had always in the past threatened the liberties of the ‘Empire of the German Nation’.

A long series of efforts to do business with Frederick William of Brandenburg ended in failure; and unfortunately he controlled the largest single force in Germany. From February 1680 until August 1682, except for one short interval, John Philip Lamberg, son of the

Hofmeister

Lamberg, struggled unavailingly in Berlin. Rébenac, the French ambassador, held the field and a sequence of agreements (in 1679, 1681, 1682, and again in 1683), linked Brandenburg firmly enough to France.

10

Frederick William’s attitude towards the great question of the day was never really in doubt. What Vienna opposed, he favoured. He argued that a public acceptance by the Emperor and the Empire of recent French gains in western Germany was the one practical policy at a time of dangerous uncertainty everywhere. He helped to frustrate Leopold, when the Hofburg wanted to make the Regensburg Diet protest officially against the occupation of Strasbourg.

11

He believed that his own treaty with Louis, in January 1682, barred further French inroads into the Empire. He sent Krockow to Vienna in August 1682, and Schwerin in the early part of 1683, to argue the case. He, and they, laid great stress on the problems of the Magyars and Turks in Hungary: in 1682 his envoy said that one reason for making peace in the Empire was the military weakness and incompetence of the Turks by contrast with the far greater weight and efficiency of Louis XIV’s army. In 1683, the second envoy preferred to plead that a firm peace in the Empire was indispensable if the Turks were to be resisted with any success. If the Emperor and the Empire accepted the French demands to date, Frederick William was willing to co-operate in reorganising the defence of Germany, and to negotiate a separate treaty with Leopold. On both occasions Hocher and his colleagues firmly rejected the argument.

12

Another envoy, from another of the great families of Habsburg noblemen, had been doing his best in a different quarter. Ferdinand Lobkowitz first visited Munich officially in November 1679.

13

It was one of the most important centres of French influence in Germany. Throughout the previous war the lamentable effects of the Elector Ferdinand Maria’s friendship with France, and of his hostile neutrality in the course of the campaigns, were plain for every Habsburg soldier or politician to see. Bavarian territory blocked the

routes from Austria and Bohemia to south-western Germany, making it much easier for the French to operate in the upper Rhineland. It deprived the allies of resources from the whole Bavarian Circle. Early in 1679 Nostitz-Reineck, the Bohemian chancellor, first attempted to improve relations between the two courts;

14

but the death of Ferdinand Maria a few months later offered a better chance of reviving a sense of common interests which had been repudiated for so long at Munich, and Lobkowitz was instructed accordingly. The Regent Max Philip was sympathetic on a number of minor points, but he could not alter the alignments of Bavarian diplomacy in any decisive way. Soon Max Emmanuel, thrusting and youthful, got rid of his uncle the Regent; it was regarded as a blow to the Austrian interest. The new Elector had no intention of shackling himself to the political traditions handed down from Ferdinand Maria’s time, but was too shrewd and also too uninterested deliberately to reverse them. For the moment he refused to take anything very seriously except the pleasures of his court, and he let the old policy ride. He agreed to the marriage of his sister Christina to the Dauphin, which took place in 1680, and always responded guardedly to the patient Lobkowitz. The Francophile Bavarian chancellor, Caspar Schmidt, remained in office and the French ambassador at Munich held his ground.

The Habsburg ministers fared little better in Dresden. In September 1679 John George II approved a treaty with Louis XIV, which appeared to meet every French demand in return for a generous subsidy. His principal advisers, the Wolframsdorfs, uncle and nephew, were the Saxon counterparts to Schmidt at Munich, but the Crown Prince had already come far closer to joining the interests at court opposed to his father’s government and to French influence than Max Emmanuel ever did before 1683.

15

It was therefore possible for Leopold’s vigorous envoy, the Abbot of Banz, to stir up protests against John George’s latest agreement with France. Yet the Austrian initiative soon faded. The Dresden court preferred momentarily to contemplate an alliance between the more important German states, designed to steer a middle course between the systems of Vienna and Paris, rather than a firmer attachment to the Habsburg interest.

16

No radical changes were likely as long as the old Elector lived. He died in September 1680. Undoubtedly the accession of John George III was a boon to Leopold, but some time passed before he was willing or able to make his weight felt in the Empire.