The Shelter Cycle (11 page)

Authors: Peter Rock

Someone would come, would unlock the door, and Colville would have to wait, prepare himself, figure out how to get inside when that happened. Meanwhile, he'd trust that he had enough food to last until he could get to the provisions inside.

“Stay close, Kilo.”

Colville didn't approach the large metal door; he could see the locks all over it from where he stood, fifty feet away. Instead he walked the perimeter of the shelter, up along the berm. Two low turrets rose above the surface, ten-foot antennas like whips above them. Thin rectangular windows, the only way to see out when one was inside, glinted beneath the snow above them.

Walking slowly, carefully, he uncovered one round escape hatch, then the next. Two feet across, round and made of concrete, each hatch was an inset circle with a hairline gap around it, impossible to pry open. He kept on, around the perimeter, the cold wind blowing snow in every direction.

As he approached the third hatch, at the shelter's corner, he could see that the snow had already been brushed away from it. Closer, he realized that the lid was not closed, that somethingâa slim metal raspâwas wedged in the gap. He took his hand from its mitten, fit his fingertips inside, and lifted the cover on its hinge, open.

A damp smell rose from the darkness. The concrete cylinder stretched down, steel rungs along its inside. Colville leaned close, listening, the warmer air rushing past him, up from below. He lowered his pack into the opening, past the counterweight and the latch, then dropped it, listening as it rattled away, as it echoed with a solid

whump

when it hit bottom. Next he called Kilo, picked the dog up in one arm; he swung one leg inside the cylinder, then the other. One-handed, he descended, slipping into the darkness.

They emerged at the bottom into a rounded hallway. Only a few emergency lights shone, pale in the ceiling. Colville knew exactly where he was.

“Easy,” he whispered. He stepped carefully from the ladder, unable to see his feet, almost tripping over his pack as he shuffled down the hallway, past the doors of other families' quarters. He stopped at his own, pushed it open.

Taking the headlamp from his pocket, he clicked it on, off: the bunks, the faded purple seat belts across them, the bookcases, the shelves of clothes. Illuminated for an instant, gone, glowing on his retinas.

The room itself was a corrugated pipe on its side, round; there was storage underneath the bottom bed. Kneeling in the darkness, he slid the flooring aside, kicked whatever was stored there to one end, took off his hat, his jacket, and dropped them inside. It had been days since he had been so warmâthis far underground the atmosphere was like a cave's, the temperature somewhere near sixty degrees. Heat came from the geothermal energy below as well, or at least people had always said so.

He swiveled around to sit on the mattress. First he took two protein bars from his pack; then he drank from the insulated container, poured some water into the bowl-like top for Kilo. The only sound beyond the dog's drinking was the distant rush of wind; he remembered his mother saying it would be like living inside a seashell, his father answering that they'd no longer hear it, after a week or so, especially with the noise of all the other people living so close.

Sitting like this on the bunk, Colville could hardly believe he was inside; then again, he felt like he was home, that he could be nowhere else. He tightened the strap around his head, switched his headlamp back on. Its round beam slid along the floor, across the black shape of the dog, up onto the wall.

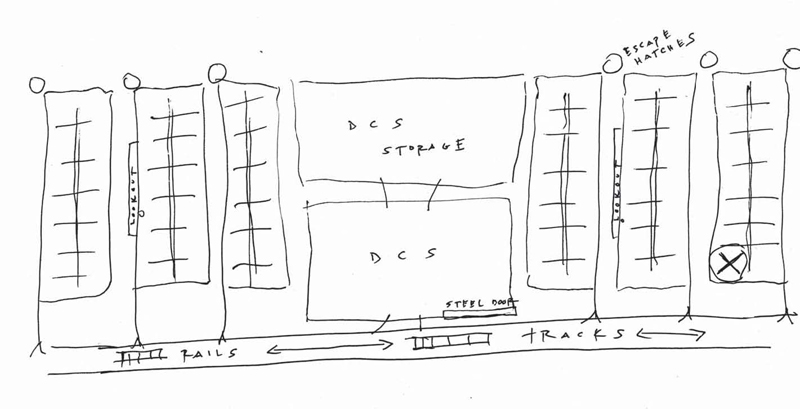

A wide sheet of white paper hung from rusted tacks: his father's diagram of the shelter. Colville started his rough copy not with the outer walls, but by drawing an

X

where he stood and then drawing the walls right around him, the section of shelter where he stood. This section, one of six, was for familiesâdifferent numbers of bunks, single and double, every conceivable space used for storage, nothing wasted. The pod where he stood would have held one hundred and twenty people; with the other five, around seven hundred, total, and in the Deep Core Storage enough food for seven years for everyone.

Â

Â

As he sketched the lines, Colville thought of all the work, the hugeness of it all. His father had spoken of the long sections of the shelter barely fitting through the narrow canyon, being brought up on trucks, piece by piece. He remembered men reading army surplus catalogs in the lunchroom; piles of packages arrived from Eddie Bauer and L.L. Bean; big wooden boxes were delivered on trucks, all the equipment that was still here, underground, around him now. His father had wired the whole shelter, and his mother had worked so hardâshe'd helped gather and organize, dehydrated and packaged the food, even when the Messenger said she should rest.

Colville carefully folded the paper when his sketch was done and put it in his pocket. He was hot, nearly sweating; he peeled off his coveralls, dropped them into the hollow space beneath the bunks. Next he slid his frame pack in and fit the piece of plywood back over it all.

His headlamp's beam shone out the doorway into the hall, onto his family's storage shelves there, all his father's books. He stepped closer.

How to Stay Alive in the Woods;

How to Live with Low-Level Radiation: A Nutritional Guide;

Sun Tzu's

Art of War;

the Boy Scouts'

Fieldbook;

Life After Doomsday;

Project: Readiness.

He reached out, but he didn't touch them.

Where There Is No Dentist; The Tracker;

Tom Brown's Guide to Wilderness Survival; The Twelfth Planet; Out-of-Place Artifacts: What Early Visitors Left Behind.

“Okay,” he said, scratching Kilo's head. “Time to look around.”

The doors to the tunnel, he'd always loved them; they looked like the doors on a submarine: rounded, with a bar that locked down from either side, a black rubber gasket around the edge that was now dry and cracked. He bent down to get through, kicked the metal rails on the tunnel's floor.

The carts were heavy, probably for mining, and could hold a lot, could be pushed in long lines as they had been before that night in 1990, piled high with sleeping bags and books and people's personal belongings, everything they'd need. He'd ridden the carts as a boy, flat on his back and kicking the corrugated top of the tunnel to scoot himself along the whole length of the shelter.

“Here, Kilo,” he said, and hoisted the dog up, kept him from leaping off. The cart's metal wheels squeaked as they passed the door to another podâone for unmarried people, if he remembered correctlyâand kept on deeper into the darkness.

At the next door he stopped pushing the cart and lifted Kilo out, then followed him into a small antechamber. Dim fluorescent lights hummed, flickered above. A table with a plywood top, hammers on it; an electric drill; a chain saw with the chain loose, tangled on itself. On the wall, a clipboard hung from a nail. Colville didn't touch it; he just leaned close. Names, dates, times, check marks. Mostly it was James, sometimes it was Stephen. Someone always came on Tuesday, usually in the afternoon. Today was Thursday, or it was Friday; he would have to keep better track.

Kilo sniffed over to the steel door, whined, returned. He could smell the world outside.

“Come on, boy.”

Deeper, past the tool roomâits walls of picks and shovels, hammers, bolt cutters, pliers and wrenchesâand around the generators and the stationary bicycles. Now Colville stood in the DCS, the first of its two chambers. No one ever called it the Deep Core Storage, really; the initials were enough. A few dim safety lights glowed in the ceiling, fifty feet above, and pallets of stores were stacked almost all the way to the very top. The beam of his headlamp reflected off the clear plastic shrink wrap, lit the tags.

Dried Fruit, Rice, Seaweed, Flour.

He walked down the aisle between the towers. His footsteps echoed; he'd heard there was a secret hollow space beneath this floor, filled with thousands of coins, gold and silver, machine guns and ammunition.

Suddenly, a loud snap, off to his left, a high-pitched cry, and then Kilo came shooting down an aisle into Colville's legs.

“Mousetraps. I said to stay close.”

They went deeper, through the gap where the chamber narrowed and opened up into the second vast space. Here the mildew was stronger; the air was thicker; the vibrations clustered, almost hummed. His headlamp shone into darkness, lit only suspended dust. Objects arose as if surfacing from deep and murky water: carts of folding chairs stacked ten feet high, the shadowy shapes of the backup generators in the electrical room, then the boxes and boxes with dates written in black marker: 11/20/82, 4/6/84, 7/4/85.

At the far end of the chamber, the round beam of his lamp circled a light switch. He knew it was a riskâno doubt someone watched the electric bills, the kilowatt hours, and any change would draw attentionâbut for one instant he switched it on, to see it all at once and not in pieces. The image flashed in his mind even after he switched the light off: here was the meeting room; the large plastic pieces of the altar; boxes stacked high, surrounded by mousetraps, a few with the dried corpses of mice in them. The smell all around him was mice, mixed with old paper. The boxes were full of dictations, and the danger was that the mice would eat all the important words, the warnings and promises of the Ascended Masters that had passed through the Messenger into the air, before being set down on paper.

The darkness closed down again, all the time collapsing, the air heavy around him. Was it nighttime? He needed to rest, to sleep. Carefully, he led Kilo back through the DCS, into the tunnel, and returned to the pod that housed his family's quarters.

Once there, he uncovered the storage space in the floor and sorted through his things. He left the sleeping bag behind, stuffed everything else into his pack, then lifted another section of the floor. The space here was full of shoes; he pushed them all to one end, then laid his pack down, slid the cover over.

There was enough room in the floor for both of themâmore than in the tent last night, and it was also warmer. Colville lay flat, the dog curled in the space between his legs. He slid the plywood over the top of them, leaving the narrowest gap to breathe through.

In that darkness he could almost hear the decrees echoing up and down the passageways; he could almost see his mother, so pregnant, decreeing with the other women, all cutting the air with their two-foot swordsârending the bad energy, slicing it loose from the air around them. His father had been coming and going, wire cutters in one hand, a voltmeter in the other. Colville had just sat on the top bunk that night, watching and listening, buckling and unbuckling the seat belt that was there in case of earthquakes or a close missile strike.

He lay still. The way he felt, it was as if right now were twenty years ago. Decrees ran through his mind, memories of being in the top bunk, his parents beneath him, waiting in the darkness, right here in this room.

And then, now, he heard a different sound. Not only the shelter's quiet roar; a howling, higher-pitched. His forehead butted the plywood as he tensed, tried to hear, to figure it. Finally he slid the cover away. He carried his boots and his headlamp as he crept past the books on their shelves, down the hallway, toward the hatch.

The sound rose higher as he approached. Not voices, not footsteps. It gusted, it almost whistled. He'd left the hatch open; the wind had picked up and now howled across the opening, like a person blowing across the mouth of a bottle.

In his stocking feet, he climbed the metal rungs, up the narrow cylinder. The air turned colder as he ascended. He stuck his head out, above the surface, and his skin stung, the hairs in his nostrils brittle. Squinting across the glowing white expanse, he could see no movement, no one approaching, no person or animal.

He stood half in the hatch, his head and torso exposed to the bitter cold. The energy hummed around him, the landscape all alive. He laughed aloud, took a deep breath. Heavy snowflakes drifted down out of the dark sky. No stars, no moon. The snow already filled his footprints from earlier today, and Kilo's paw prints. Colville looked behind him, to each side. Descending, he took hold of the rope just above the counterweight and lifted. The hatch slapped shut gently above his head. The wind's howling was gone at once, and silence thickened around him.

T

HERE WERE EIGHT

carts, all together, and Colville pushed seven of them to one end of the tunnel, out of the way. He found an oil can in the tool room and lubricated the metal wheels of the eighth cart until it ran smoothly, with a low metallic hiss. Lying on his back, holding Kilo pressed against him, he kicked along the ceiling of the tunnel and the cart shot through the darkness. He covered the hundred yards in less than thirty seconds. To slow down, he let the toes of his boots drag along the corrugated metal above.

He wandered, he searched. His headlamp's beam shone like a bright rope that pulled him deeper into the darkness, toward new discoveries. Turning corners, he still expected to meet the boys he'd known, or their parents, to hear decrees or see the men with the radiation gauges, measuring everyone who came in from outside. He wore a pair of his father's tennis shoes, their laces replaced with wire. The down vest, tooâhe could remember his father wearing it; when he pulled it out of the cubby, the black electrical tape that had been used to patch it fell off, slippery now on both sides. As he walked, he nervously held one hand over the rip, as if the little white feathers might alert someone to his presence.