The Shadow Dragons (11 page)

Read The Shadow Dragons Online

Authors: James A. Owen

Traveling so directly north, the only islands they passed that were familiar to them were Prydain and a small group of islands called the Capa Blanca. Prydain was one of the greater islands, second only to the capital island of Paralon, but the Caretakers had never actually traveled to the Capa Blanca islands before.

“I understood from the Histories Bert wrote that they were originally settled by shipwrecked sailors from Spain,” Charles remarked, feeling a chill now that the sun was setting. “The sailors built several very lovely towns and had quite a nice culture developing until some British doctor showed up and taught the animals there how to talk. After that it was all downhill. The animals wanted better working conditions and higher wages. You know how it goes.”

“Spanish, eh?” said Quixote. “Perhaps we could stop in on our way home. It’s been too long since I heard my native tongue.”

“Doesn’t Verne speak Spanish?” asked Jack.

“Dreadfully,” said Quixote. “I made him promise to never again make the attempt.”

The last island they passed, the easternmost and most northerly island in the

Geographica,

was a midsize round island called Gondour.

“They’re quite the democracy, according to Mark Twain’s notes,” said John, “although I never did care for his spelling of the name. Always have to catch myself when I mispronounce it ‘dour’ instead of ‘door.’”

“Aren’t they assisting Artus with his new republic?” asked Jack.

“I think so. The one oddity is that they are a republic ruled over by an impeachable caliph. I’d imagine it makes for some very lively debates.”

After Gondour, there was going to be very little to see for a long while, so the companions made themselves as comfortable as they could in the

Scarlet Dragon,

and took turns sleeping. Jack and Quixote volunteered for the first watch and took up positions at the fore of the boat.

“Jack, may I ask you something?” said Quixote.

“Certainly.”

“Have you ever known failure?”

Jack turned to the knight in surprise. “Of course I have. Everyone does, at one time or another.”

The knight chewed on his lip as he pondered Jack’s reply. “I thought I had failed, once,” he said at length, “but I am wondering if that event was not part of my own destiny, Prophecy or no.”

“How do you mean?”

“I think I know why I am here, with you,” said Quixote. “I think I understand, at least in part, my role. I am owed a debt—and my claiming it may be a key to all that we are experiencing.”

“Who owes you the debt?” asked Jack.

“The Lady,” Quixote replied. “The Lady of the Lake.”

He turned away and said no more, and Jack was reluctant to press him. The rest of the night passed without incident.

In the morning John again instructed Charles to sprawl himself against the masthead so that they could better read the map.

“This is not very dignified, you know,” Charles pouted. “Can’t you just sketch out a copy in the

Geographica,

so I can keep my shirt on?”

“Sorry, old boy,” said John. “Some of the islands have already changed position.”

It was true—the locations of several of the Nameless Isles had moved during the night. John made some corrections and adjusted the tiller on the

Scarlet Dragon

to communicate the changes to the boat.

“If all goes as I hope it shall,” John said, “we ought to be there by nightfall.”

The course the map took them on led them safely distant from the kingdom of the Trolls, farther to the west—which was for the best, as none of the companions had ever liked Arawn, the former prince who was now king of the Trolls. He had been a rabble-rouser during their first encounter with the Winter King, and later allied with him against them. Arawn had been as ungracious in defeat as Artus had been gracious in his victory, and so the Northlands had been a place to avoid ever since—if they could help it.

The islands of the Christmas Saint, past the Troll Kingdom, were the absolute northernmost chronicled in the

Geographica.

All three companions had read the annotations thoroughly, and very early on in their role as Caretakers had conspired to find reasons to correspond with and eventually visit the principal resident. John had even gone so far as to persuade him to write letters to his children, which was one of the great delights of fatherhood. To know beyond a doubt that Father Christmas existed was spectacular enough; to be considered worthy of corresponding with him was a childhood dream made manifest.

Beyond the isles of Father Christmas, there was nothing. Nothing in the

Geographica,

and nothing as far as the companions could see. None of the previous Caretakers had ever made the effort to sail so far—they had simply assumed that what had been documented was all there was to see. Of them all, only John’s mentor, Professor Sigurdsson, had ever taken an active liking to the actual adventuring, the discovery of new lands. He had ventured deep into the Southlands on a fabled voyage, and more than once into the deep west—although John had no clue what he could have been searching for, or what else could be discovered that way, since Terminus and the endless waterfall marked the true End of the World as he knew it.

Charles, when he was not putting on his shirt and taking it off again so the others could check their position, spent his time talking about multiple dimensions with Archimedes, who had proven to be a worthy adversary in a debate.

Quixote preferred to talk to Rose when he could, asking her about the more mundane aspects of boarding school in Reading, with an occasional digression to tales of Odysseus on Avalon.

Jack, for his part, spent the better part of an hour scanning the horizon with a spyglass provided to him by Quixote, until he finally realized that there was no actual glass in the spyglass.

“I never really needed it.” Quixote shrugged. “It doesn’t help if you’re lost, and if you aren’t lost, why do you need to see a place you’ll soon arrive at anyway?”

Eventually, as the Cartographer had promised, a smudge of land appeared off in the distance, then grew larger at an alarming speed. The Nameless Isles were far closer than they had appeared to be, and had the appearance of a mirage. It took effort to focus on them—a moment of drifting attention found the islands sliding from one’s field of vision.

At close range the illusion dropped, and the islands came into sharp relief. There were thirteen all told: a massive island to the south and east of the others, which served as a shield of stone; a small cluster of islands to the west; two larger, half-moon islands to the east and north; and directly ahead of them, a broad, dunecolored island that sloped up from a short beach to a flat expanse of sand, black crystals, and short, blocky trees.

All of the smaller islands had been built up with columns and arches that were all but prehistoric. From their appearance, their construction, and their apparent great age, John surmised that they may have been built in the earliest years of prehistory— contemporary with the first cities, such as Ur and Untapishim. The structures on these outer isles formed a kind of massive arena enclosing the three inner islands. There was no mistaking the purpose: They were defensive, or at least protective, in nature.

On the center island was the unmistakable shape of a house in the distance—and from all appearances it was immense. Directly ahead was a dock, a small boathouse, and a sight that made the companions cheer in joy and relief.

The

White Dragon,

the airship piloted by their mentor Bert, was moored to the north side of the dock, where it floated calmly in the shallows.

“I suddenly feel much better about the prospects of this trip,” Charles admitted. “Nothing against you fellows, but Bert always seems to know the score.”

“I’m with you there,” said John. He guided the

Scarlet Dragon

alongside the larger ship and leaped to the dock to tie a mooring line.

A large orange cat was sitting just past the dock, idly cleaning itself while keeping a watchful eye on the new arrivals to the island.

“I expect you must be the Caretakers,” the cat said at length. “Come ashore. You’re expected.”

“Are you the welcoming committee?” Charles asked as he jumped to the dock and looped the mooring ties to a pylon. “If so, I’m pleased to meet you.”

“I am what I am,” the cat said, “and if that pleases you, so be it.”

“What does that mean?” asked Jack.

“It means,” the cat replied, tipping its head toward Rose, “that I am like her. Here, and not here, all at once.”

“A riddle?” said John.

“An enigma,” said Rose.

“A conundrum,” said the cat, which tilted its head, then began to disappear.

“My word,” said Charles. “The cat! It’s vanishing!”

“No,” said the cat, which by now was nothing more than a head, floating in the air. “I’m simply going to a place you aren’t looking.”

“That makes perfect sense,” said Rose.

“It’s very confusing,” said Jack.

“Thank you very much,” said the broad smile that was once a whole cat. “You may call me Grimalkin. Welcome to Tamerlane House.”

The House of Tamerlane

The Magician

and the Detective pulled the door out of the ship’s hold and dragged it across the field to where the construction was taking place. There were carpenters and bricklayers and all manner of roustabouts scattered across the worksite who were carrying materials and banging on things and generally trying to look busy. But everything always stopped when they delivered a door.

Just so,

the Magician thought.

The rabble should stop and take notice when I’m onstage.

It might not be a formal performance as such, but he and the Detective were performing the job that could only be trusted to the betters of these rabble.

“Are you two idiots going to take all day dragging that door over here?” said a brusque voice.

At the top of the rise, holding the project blueprints, stood a solid man whose eyes glittered with purpose and whose scarred cheeks testified to his will. Richard Burton was not one to suffer fools or layabouts—not for long, anyway.

“Bring it up here,” Burton instructed them, pointing to a frame that had been erected on a patch of clover. “Carefully, now. The Chancellor will not be pleased if we lose another one. Nor will I.”

A few months earlier they had been bringing another door up the rise when some of the workers dropped a wheelbarrow load of bricks from the scaffolding high above. The bricks had struck the door with enough force to shatter it, and splinters were all that was left. Burton had examined them with an Infinite Loupe—a modified set of eyeglasses that could be used to see through time— and proclaimed it to have been linked to the ninth century.

“And to Persia, unless I miss my guess,” Burton had said. “That could have been useful—but it isn’t a time or place that is wholly unknown to me, so we’ll let it go, for now.”

Of course, Burton’s idea of “letting it go” meant beheading the workers who had spilled the bricks, but since it was also useful in motivating the rest of the workers to be more careful, he didn’t see it as a complete waste of effort and resources.

The Detective and the Magician stood the door in place and fitted it to the frame, then stepped back.

Burton wiped his hands on his leather apron and stepped up to the door. Cautiously he reached for the handle and slowly pulled the door open, careful not to step over the threshold.

A bright light emanated from within, giving Burton’s harsh features a demonic cast. Baroque-period music could be heard from somewhere deep in whatever place the door had opened to. “Excellent,” he said as he closed the door. “The Chancellor will be very pleased. A few more, and we’ll be able to give the order to move forward. A few more doors . . .

“. . . and we’ll be able to conquer all of creation.”

The central island of the Nameless Isles was practically barren of vegetation, save for a number of massive stumps of petrified wood, and the black obsidian crystals that were scattered among the dunes.

At the end of the dock, a path formed of obsidian pieces wound its way up the slope to the front door of the extraordinary dwelling Grimalkin had called Tamerlane House.

It was a Persian palace, both ancient and exotically new all at once. It was massive in an organic way, wings spreading out across the rise like the branches of an enormous tree. There was very little in their experience that it could be compared to, but John had heard stories of the fabled Winchester House in California, which had been built by an heiress to the Winchester rifle fortune to house the spirits of those who had been killed by the rifles. She built endless rooms, and stairways, and closets, and alcoves, and on and on and on. For decades the hammers never stopped. And for the first time, John was looking at a similar structure born of a similar obsession. He wondered with a mixture of curiosity and fear just what kind of spirits were meant to be housed in Tamerlane House.

In answer to his unspoken question, a familiar figure, looking only slightly more presentable than his usual charmingly bedraggled self, appeared at the top of the steps. It was Bert.

The three Caretakers rushed forward to shake hands and embrace their mentor, who appeared equally glad to see them. Rose hugged him tightly as he kissed the top of her head, and even Archimedes restrained himself to a polite greeting that was hardly sarcastic at all.

“You’re a tall drink of water,” Bert said, shielding his eyes from the sun as he looked up at Quixote, who bowed in greeting. “How did you get pulled into joining this motley crew?”

“He pretty much had to come,” explained Jack. “His room was about to fall into the Chamenos Liber.”

“His room . . . ?” Bert said. He blinked a few times, then moved closer to the old knight. “Are you Don Quixote?”

A deeper bow this time. “I

am

Don Quixote de la Mancha,” he said with a flourish, “and I am your humble servant.”

“Does he have to do that every time he meets someone?” Jack asked John.

“It certainly makes him memorable,” John replied. “Maybe you should try it with your next reading class.”

“Har har har,” said Jack.

“I know all about you,” Bert said to Quixote with a gleam in his eye, as his old familiar twinkle began to reappear. “Jules has told me many things—and while your presence is a surprise, it is not wholly unexpected.

“Come,” he went on, gesturing for them to follow as he turned to enter the house. “There is much to talk about, now that you’ve finally arrived.”

“We were expected?” exclaimed Jack.

Bert grinned wryly. “Of course. Ransom told us what happened seven years ago, so we’ve been waiting. Otherwise, you wouldn’t have gotten past Grimalkin.”

“The Cheshire?” said John. “He seemed pretty harmless to me.”

“He may look like a simple Cheshire cat,” said Bert, looking around cautiously to see if Grimalkin was listening, “but in reality, he’s one of those Elder Gods that fellow Lovecraft has been writing about.”

“You’re kidding, right?” said Charles. “It’s a joke.”

“Laugh if you like,” Bert called over his shoulder, “but if I were you, I wouldn’t take off his collar. For

any

reason.”

“As I was saying, we had an idea what had happened to you when Ransom reported in,” Bert said as he served the companions tea and Leprechaun crackers in an elaborate parlor, “so we hoped you’d make your way to the Nameless Isles, as Hank had suggested.”

“I must admit, Bert,” said John, trying not to sound as if he were chiding the older man, “as the Caretaker Principia, I was a bit put out to find there were islands I was unaware of—indeed, islands I was not

allowed

to know of.”

“I am sorry about that, John,” Bert replied. “Had it been up to me, I’d have said something to you much sooner. It’s been a matter of some debate, my position being that if you had been aware, you could have come here directly from Oxford, and not skipped over seven vital years.”

“Debate with whom?”

“The Prime Caretaker. But we will discuss that shortly.” Bert stood up. “For now, we should make some accommodations for Rose and the good sir knight.”

“You rang?” Grimalkin said, appearing on the back of a couch.

“Ah, Grimalkin,” said Bert. “Yes, please. If you would be so kind as to show the lady and her gentleman escort to their rooms?”

“Certainly,” said Grimalkin, eyeing Archimedes. “Do I get the bird to play with?”

“Define ’play,’” said Bert.

“Oh, never mind,” said the cat as his body faded out to nothingness. “Come this way.”

“He’ll take care of you,” said Bert. “Just follow his head.”

“I could use a rest, I think,” Quixote said. “Thank you, master Caretaker.”

As the two companions and the reluctant owl followed the bobbing cat’s head down a corridor, Bert turned back to the Caretakers. “Now we can talk as men do, about things of import and consequence.”

“Will she be safe here, Bert?” asked John.

“Safe as houses,” Bert replied, “or at least, as safe houses. She has nothing to fear here. Grimalkin will look after her, and no one may come here who wasn’t invited. That’s one of the reasons these islands have remained nameless, and why no map of them exists in the

Geographica.

This place is our own version of Haven, to withdraw to when we must, or when circumstances are most dire.”

“Well, we’ve certainly got a map now,” Charles said, scratching at his side. “Does it keep moving even when we’ve arrived here?”

“The Cartographer cornered you for the duty, eh, Charles?” said Bert with a grin. “It’s easier when you’re traveling with friends. My first trip here was solo, and I had to use a mirror.”

Suddenly a flock of birds barreled down the hallway, each carrying silverware and china place settings. As in the Great Whatsit on Paralon, the servants of the house were large black birds, who were dressed nattily in vests and waistcoats.

“Crows?” Jack asked as the last of the birds flew out of the hallway.

“Ravens,” Bert corrected him. “A full unkindness.”

“I’ll take an unkindness of ravens over a murder of crows any day,” said Charles.

“Your jokes are still both literate and unfunny,” said Bert, hugging Charles around the shoulders. “It’s so good to see you again, lad!”

Bert led the three friends through room after room, but other than the ravens, the house appeared empty.

“Is there anyone here?” Jack asked, peering up at a stairwell that ended, inexplicably, at the high ceiling. “The place seems to be abandoned.”

“The master of the house is indeed here in residence,” said Bert, “but he seldom chooses to appear. You may meet him after the Gatherum.”

“The what?” asked John.

“Better I simply show you than try to explain,” Bert said with deliberate mystery and a touch of glee. “Here—I want to show you the Pygmalion Gallery,” he continued, waving them down another long corridor. “In fact, I’ve wanted to bring you here for a very long time.”

“What prevented you?” asked John.

“Those evil stepsisters, Necessity and Planning,” Bert replied as they approached a set of tall polished doors. “One always gets too little attention, and the other too much—and they never seem to balance out.”

The doors were covered with cherubs, and angels, and all manner of ornate and byzantine carvings. In the center, where the doors met, were three locks. Bert removed a large iron ring with two heavy skeleton keys from his pocket. He unlocked the first lock, then the next.

“Three locks,” Charles said, “but only two keys?”

“The third key is imaginary,” explained Bert. “It’s a safety feature.” He made the motions of choosing a key and inserting it into the third lock, and the companions were all surprised to hear a loud click.

“It’s always the most difficult,” said Bert. “You have to turn it just so.”

The gas lamps came up as they entered an anteroom. Beyond was a spacious gallery, with velvet-lined walls, lush oriental carpets, and high ceilings that irised to a circular skylight. The walls were covered with paintings—portraits, John noted, that were almost life-size and large enough to step through.

“An astute observation, young John,” Bert said. “Do you recognize any of the portraits?”

“Any of them?” said Charles excitedly. “I recognize them all!”

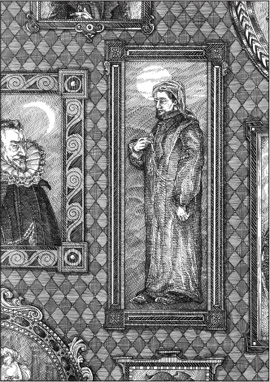

In the center of the north wall was a full-figured portrait of Geoffrey Chaucer, and slightly smaller portraits of Sir Thomas Malory and Goethe hung to the right and left of it. On the south wall, directly across from Malory’s portrait, was an equally large painting of Miguel de Cervantes, flanked by portraits of Franz Schubert and Jonathan Swift. Next to Swift, the companions each noted with barely concealed surprise, was a portrait of Rudyard Kipling, appearing exactly as he had at the Flying Dragon.

Kepler was there, as were William Shakespeare and Nathaniel Hawthorne. Jack was almost as good as Charles at identifying the portraits, but John was having a harder time of it.

“I recognize Twain, and Dickens,” he said to Bert, “but I’m really at a loss for several of the others.”

“Surely you know Daniel Defoe”—Bert indicated an exceptional portrait set in a rather ordinary frame— “and of course Alexandre Dumas

père.

“This is where the most important debates about the Archipelago of Dreams take place,” he went on somberly, his voice hushed as the four men walked deeper into the gallery proper. “Within this room is the greatest collection of knowledge and wisdom to be found in any world.”

“I thought that was the Great Whatsit, on Paralon,” said Charles.

“That is a great repository of learning, yes,” said Bert, “but you cannot have a discussion with a book, or debate with a parchment.”

“And we’re supposed to fare better talking to paintings?” Jack said as he leaned close to examine a portrait of Washington Irving.

“That may depend more on your own skills,” Bert replied mysteriously, “than on the conversational skills of any particular painting.

“Gentlemen,” he announced with a flourish, “I’d like you to meet your predecessors, those who have gone before you in the most important job in creation: Behold the Caretakers Emeritis of the

Imaginarium Geographica”