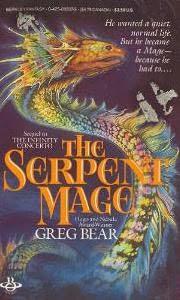

The Serpent Mage

Authors: Greg Bear

The Serpent Mage

Songs of Earth and Power Vol. 2

Greg Bear

Contents

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-One

Chapter Thirty-Two

Chapter Thirty-Three

Chapter Thirty-Four

Chapter Thirty-Five

Chapter Thirty-Six

Chapter Thirty-Seven

Chapter Thirty-Eight

Chapter Thirty-Nine

Chapter Forty

Afterword

Copyright © Greg Bear 1984,1986 Afterword © Greg Bear

All Rights Reserved

To Betty Chater dear friend, teacher, and colleague and for Kristine, a kind of Beatrice

Chapter One

Are you ready?

The pale, translucent forms bent over Michael Perrin once again. Had he been awake, he would have recognized three of them, but he was in a deep and dreamless sleep. Sleep was a habit he had reacquired since his return. It took him away, however briefly, from thoughts of what had happened in the Realm.

He is pretending to be normal

, one form said without words to her sister, hovering nearby.

Let him rest. His time will come soon enough.

Does he feel it?

He must.

Has he told anybody yet?

Not his parents. Not his closest friends.

He has so few close friends…

Michael rolled over onto his back, pulling sheet and blankets aside to reveal his broad, well-muscled shoulders. One of the forms reached down to squeeze an arm with long fingers.

Stop that.

He keeps himself fit.

The fourth figure, shaped like a bird, said nothing. It stood by the door, lost in thought. The others retreated from the bed.

The fourth finally spoke.

No one in the Council knows of this

.

It was a surprise even to us

, the tallest of the three said.

Michael's eyelids flickered, then opened. He caught a glimpse of white vapor spread like wings, but it could easily have been the fog of sleep. With a start, he held up his left wrist to look at his new watch. It was eight-thirty. He had slept in. There would barely be time for his exercises.

He descended the stairs in a beige sweatsuit, a gift from his parents on his last birthday. There had been no candles on his cake, at his request. He did not know how old he was.

His mother, Ruth, was reading the newspaper in the kitchen. "French toast in fifteen minutes," she warned, smiling at him. "Your father's in the shop."

Michael returned the smile and picked up a long oak stick from beside the kitchen pantry, carrying it through the door into the back yard.

The morning was grayed by a thin fog that would burn off in just a few hours. Near the upswung door of the converted garage, his father, John, was hand-sanding a maple table top on two paint-spattered sawhorses. He looked up at Michael and forearmed mock-sweat from his brow.

"My son, the jock," Ruth said from the back steps.

"I seem to remember him still carrying stacks of books around," John said. "Don't be too hard on him."

"Breakfast lingers for no man," she said. "Fifteen minutes."

John wiped the smooth pale surface with his fingers and applied himself to a rough spot. Michael stood in the middle of the yard and began exercising with the stick, running in place with it held out before him, hefting it back over his head and bending over to touch first one end, then the other to the grass on both sides. He had barely worked up a sweat when Ruth appeared in the doorway again.

"Time," she said.

She regarded her son delicately over a cup of coffee as he ate his French toast and strips of bacon. He was less enthusiastic about bacon — or any kind of meat — than he had been before…

But she did not bring up this observation. The subject of Michael's missing five years was virtually tabu around the house. John had asked once, and Michael had shown signs of volunteering… And Ruth's reaction, a stiff kind of panic, voice high-pitched, had shut both of them up immediately. She had made it quite clear she did not want to talk about it.

Just as clearly, there were things she wanted to tell and could not. John had been through this before; Michael had not. The stalemate bothered him.

"Delicious," he said as he carried his plate to the sink. He kissed Ruth on the cheek and ran up the stairs to change into his work clothes.

Michael had not yet assumed the position of caretaker at the Waltiri house. The time was not right.

After two weeks of job hunting, he had been hired as a waiter in a Nicaraguan restaurant on Pico. For the past three months, he had taken the bus to work each weekday and Saturday morning.

At ten-thirty, Michael met the owners, Bert and Olive Cantor, at the front of the restaurant. Bert pulled out a thick ring of keys and opened the single wood-framed glass door. Olive smiled warmly at Michael, and Bert stared fixedly at nothing in particular until he was given a huge mug of coffee. Shortly after the mug was empty, Bert began issuing polite orders in the form of requests, and the day officially started. Jesus, the Nicaraguan chef, who had arrived before six o'clock, entering through the rear, donned his apron and cap and instructed two Mexican assistants on final preparations for the day's specials. Juanita, the eldest waitress, a stout Colombian, bustled about making sure all the set-ups were properly done and the salad bar in order.

Bert and Olive treated him like a lost son or at least a well-regarded cousin. They treated all their employees as if they came from various branches of the family. Bert had called the restaurant his "United Nations retirement home" after hiring Michael. "We have a red-headed Irishman, or a lookalike anyway, and half a dozen different types of Latinos, and two crazy Jews in charge."

Michael served on the lunch and early dinner shifts, and he studied the people he served. The restaurant attracted a broad cross-section of Los Angelenos, from Nicaraguans hungry for a taste of home to students from UCLA. Lunchtime brought in white-collar types from miles around.

This morning, Bert's mug of coffee did not settle him firmly into the day. He seemed vaguely distraught, and Olive was unusually subdued. Finally, a half-hour before opening, Bert took Michael into the back storeroom behind the kitchen, among the huge cans of peppers and condiments and the packages of dried herbs, and pulled out two chairs from a small table where Olive usually sat to do the books.

Bert was sixty-five, almost bald, with the remaining white hair meticulously styled in a wispy swirl. He could be relied upon to always wear a blue blazer and brown pants with a golf shirt beneath the blazer, and on his right hand he sported a high school class ring with a jutting garnet.

He waved this hand in small circles as he sat and shook his head. "Now don't worry about whether you're in trouble or not. You're a good worker," he said, "and you wait tables like an old pro, and you're graceful and you could even work in a snazzy place."

"This

is

a snazzy place," Michael replied.

"Yes, yes." Bert looked dubious. "We're a family. You're part of the family. I'm saying this because you're going to work here as long as you want, and we all like you… but you don't belong." He stared intently at Michael. "And I don't mean because you should be in a university. Where are you coming from?"

"I was born here," Michael answered, knowing that was also not what Bert meant.

"So? Why did you come

here

, to this restaurant?"

"I don't know what you're getting at."

"The way you look at customers. Friendly, but… Spooky. Distant. Like you're coming from someplace a hell of a long ways from here. They don't notice. I do. So does Juanita. She thinks you're a

brujo

, pardon my Spanish."

Michael had learned enough Spanish as a California boy to puzzle out the

brujo

was the masculine for

bruja

, witch. "That's silly," he said, staring off at the cans on their gray metal shelves.

"I agree with her. Maybe even, pardon me, a

dybbuk

. Juanita washes dishes, and I taste the food and maybe yell once a week, but that's both our opinions. Both ends of the rainbow think alike."

"What does Olive think?" Michael asked softly. Olive reminded him of a slightly plumper Golda Waltiri.

"Olive would like to have half a dozen sons, and the Lord, bless him, did not agree. She adores you. She does not think ill of you even when she sees the way you 'learn' our customers, the way you

see

them."

"I'm sorry I'm upsetting you," Michael said.

"Not at all. People come back. People, who knows why, enjoy being paid attention to the way you do it. You're not in it for the advantage. But you still don't belong here."

The room was small, and Bert was wearing his look of intense concern, raised brows corrugating his high forehead. "Olive says you have a poet's air about you. She should know. She dated a lot of poets when she was young." He cast a quick, long-suffering look at the ceiling. "So why are you waiting tables?"

"I need to learn some things."

"What can you learn in a trendy little dive on Pico?"

"About people."

"People are everywhere."

"I'm not used to being… normal," Michael said. "I mean, being with people who are just… people. Good, plain people. I don't know much about them."

Bert pushed out his lips and nodded. "Juanita says that for somebody to become a

brujo

, something has to happen to them. Did something happen to you?" He raised his eyebrows, practically demanding candor. Michael felt oddly willing to comply.

"Yes," he said.

Having struck pay dirt, Bert leaned back and seemed temporarily at a loss for what to ask next. "Are your folks okay?"

"They're fine," Michael said abstractedly.

"Do they know?"

"I haven't told them."

"Why not? They love you."

"Yes. I love them." The dread was fading. Michael did not know why, but he was going to open up to Bert Cantor. "I've tried telling them. It's almost come out once or twice. But Mom gets upset even before I begin. And then, it just stops, and that's it."

"How old are you?"

"I don't know," Michael said. "I could be seventeen, and I could be twenty-two."

"That's odd," Bert said.

"Yes," Michael agreed.

The story spun itself out from there, across several days, each day at eleven Bert drawing up the chairs and sitting across from Michael with his corrugated forehead, listening until the lunchtime crowd arrived and Michael began waiting tables.

On the fourth day, the story essentially told, Bert leaned back in his chair and closed his eyes, nodding. "That," he said, "is a good story. Like Singer or Aleichem. A good story. This part about Jehovah being a Fairy, that's tough on me. But it's a good one. And I'm not asking to insult you — but, it's all true?"

Michael nodded.

"Everything's different from what the newspapers and history books say?"

"

Lots

of things are different from what they say, yes."

"I'm asking myself if I believe you. Maybe I do. Sometimes my opinions are funny that way. You're sure it's better here than going to college?"

He nodded again.

"Smart boy. My son James, from a previous marriage, he's gone to college, the professors there don't know

frijoles

about people. Books they know."

"I love books. I've been reading every day, going to the library after I read all the books my folks own. I need to know more about that, too."

"Nothing wrong with books," Bert agreed. "But at least you're trying to put things in perspective."

"I hope I do."

"Well," Bert said, with a long pause after. "What are you going to do about yourself?"

Michael shook his head.

"I feel for you, with a story like that," Bert said. Then he stood. "Time to wait tables."

The winter passed through

Los

Angeles more like an extended autumn, crossing imperceptibly into a wet and clean-aired spring such as the city had not seen in years, a sparkling, green-leafed, sun-in-water-drop spring.

The pearls appeared in Michael's palms six months after his return from the Realm, in the first weeks of that spring. They nestled at the end of his lifeline, insubstantial, glowing in the dark like two fireflies. In two days' time, they faded and disappeared.

The pearls confirmed what he had suspected for some weeks. Events were coming to fruition.

So ended the pretending, his time of normality and anonymity, the last time he could truly call his own.

Rain fell for several hours after dinner, pattering on the roof above Michael's room and chirruping down the gutters. Moonlit beads of moisture glittered on the leaves of the apricot and avocado trees in the rear yard. Rounded lines of clouds, their bottoms turned orange-brown by the city lights, moved without haste over the Hollywood hills.

Michael had come upstairs to read, but he put down his book — Evans-Wentz's

The Fairy-Faith in Celtic Countries

— and went to stand before the open window, feeling the moist air lap against his face.

The night birds were singing again, their trills sharp and liquid by turns. The trees seemed alive with song. He hadn't heard them singing this late in months; perhaps the rain had disturbed them.

Michael closed the window, returning to his bed and leaning back on the pillow. He slept naked, disliking the restriction of pajamas while he lay in bed, while his mind acted like an antenna, extending itself and receiving, whether he willed it or not…

Tomorrow, Michael would leave the home of his parents to live in the house of Arno and Golda Waltiri and assume control of the estate. He had planned the move since telling Bert and Olive he was quitting, but the time had never seemed exactly right.

Now it was right. Even discounting the pearls, unmistakable signs were presenting themselves stacked one upon the other. He was having unusual dreams.

He turned off the light. Downstairs, a Mozart piano piece — he didn't know which one — played on his father's stereo. He felt drowsy, and yet some portion of his mind was alert, even eager. Moonlight filled his room suddenly as the shadow of a cloud passed. Even with his eyes closed to slits, he could clearly make out the framed print of Bonestell's painting of Saturn seen from one of its closer moons.

For the merest instant, on the cusp between sleep and waking, he saw a figure crossing the print's moon landscape. The print was not in focus, but the figure was sharp and clear. A young — very young — Arno Waltiri, smiling and beckoning…