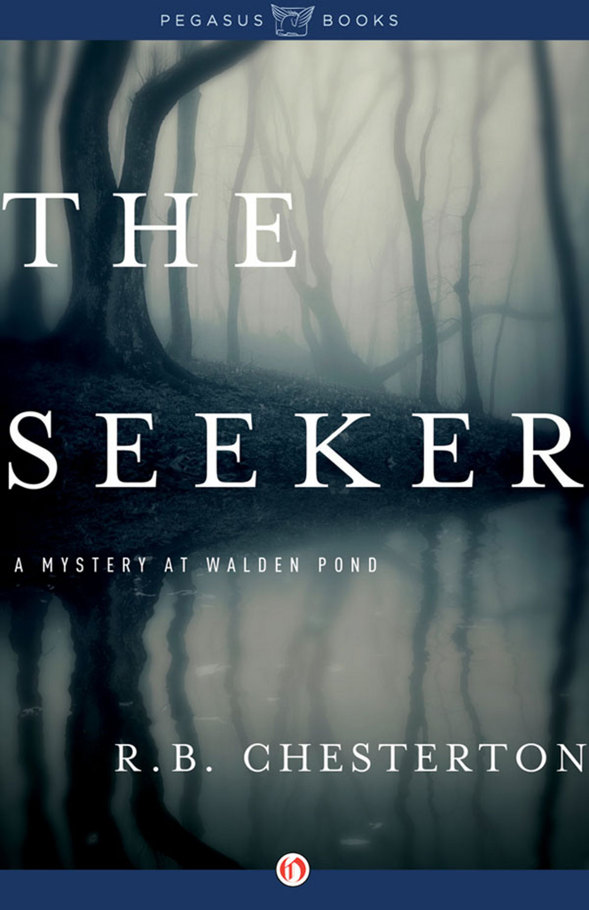

The Seeker A Novel (R. B. Chesterton)

Read The Seeker A Novel (R. B. Chesterton) Online

Authors: R. B. Chesterton

Tags: #Fiction, #Thrillers, #General

The Seeker

R. B. Chesterton

For my sister Susan Haines, HH, and all the readers who love a good scare.

And for Kristine, who gave me the key to unlock this story.

Contents

“Let nothing come between you and the light.”

Henry David Thoreau,

Letters to a Spiritual Seeker

Prologue

My grandmother was born with a port wine stain on the left side of her face. The exact shape of Narragansett Bay, the birthmark ran down from her eye to touch the corner of her mouth. In moments of anger, it pulsed with a purplish cast but otherwise was a dark red. Siobhan Cahill was her name. Though she never married, she gave birth to a son, my father, Caleb.

To know who a person is, you must know his history, Granny Siobhan told me. Our family’s history has a nasty habit of repeating itself.

Shortly after the turn of the 18th century, my ancestor Jonah Cahill abandoned the old, superstitious ways of his tribe of Irish travelers and bought land on the western coast of the Emerald Isle. He was a pious man with a strong personal attachment to his god. He established a grand farm in Galway, Ireland and in the span of ten years built an empire of cultivated fields that stretched across the rolling hills as far as the eye could see. Jonah meant to grow things, from potatoes to children. And he did. He produced seven stout boys, two beautiful girls, and neat productive fields bordered by stone walls.

For two decades the sun shone on Jonah and nature blessed each thing he turned his hand to. The Great Frost put an end to his ambitions. In December 1739, Ireland and most of Europe froze. The bitter cold iced potatoes in the ground, eliminating the major food source and destroying seeds for the next year’s crops. Coal shipments from Wales, the primary means of warmth, jammed the frozen rivers. Desperate, the Irish stripped the land of burnable trees and shrubs. With no fuel to keep warm and no food to eat, Jonah’s family began the process of slow starvation.

They endured for two years, managing to keep oatmeal on the table, but the farm was a ruin. The crops were destroyed, the animals dead. With no relief in sight, Jonah took his sons and emigrated to the New World in 1742.

Though many of the

Kathlene

’s passengers and half the crew died on the tempestuous, brutal voyage, Jonah Cahill, named for a minor prophet of the Old Testament, was as solid as an oak. He and the boys made the passage alive. They landed in Boston Harbor and moved inland to soil that had never seen a plow. His intention was to make enough money in the New World to buy passage for his wife and two daughters.

Jonah worked against the clock, knowing that with each passing week Margaret and the girls struggled to survive. He and his sons sold turnips, firewood, wild berries, honey, and poteen they brewed in small pots behind their makeshift shed of a home, each penny hoarded. Jonah was tormented by dreams of the frigid cabin in Ireland. Thrashing and sweating each night, he saw Margaret weakening with the harsh task of survival, the girls with no man to help them, searching for firewood and enough oatmeal or scraps to keep body and soul together.

Jonah bargained with god. He tithed and continued deeds of charity. And the Cahill males worked without rest until the money for passage was secured. Two winters passed with no word from Ireland. He left the boys to mind the family ventures and went to collect the rest of his family.

He found the Galway farm demolished, the house and fences burned for fuel. His wife and daughters gone.

He learned from neighbors that starvation had taken them only two months after he left. His work—and his bargains with god—had all been in vain. Margaret buried both daughters. She’d died in the field attempting to dig frozen potatoes from the icy ground. No one had thought to mark their graves, and because there was no money to buy a blessing from the church or proper burial, they’d been left in unsanctified ground.

For two weeks Jonah dug up the fields, searching for the bodies. He never found them. Before he left Ireland, he cursed the God he’d served so diligently and pledged his future to a darker entity.

Granny Siobhan said this was the beginning of the black luck and blacker deeds that grew to define the Cahills.

Jonah returned to Massachusetts, sold the farm, and moved his sons to Rhode Island. They cast their lot with the sea—the land had betrayed them, and Jonah Cahill swore that he’d rely no more on sod for survival. Turned out the Cahills had a knack for sailing. And butchery. Jonah and his boys vented their fury on the whales that populated the northern Atlantic Ocean. They came to be known as the most brutal slayers of the sperm whale, taking high numbers a year for the fat and ambergris, which was rendered into lamp oil and perfume.

The Cahill reputation for savagery spread to their competitors. Rumors of scuttling and burning ships drifted back to shore even as the ships and sailors did not. At least twice Jonah was arrested, but there was no proof against him. He grew meaner and more dangerous. One by one, the boys found wives, but peculiar maladies struck the family. And it only made Jonah more defiant.

For better than a century, the Cahills took their living from the sea, but changing times demanded a new approach.

With civil war looming, the Cahills left Rhode Island and settled in the Kentucky mountains “before the law could pull tight the noose around their necks,” as Granny told it. In 1860, they took their pirating and scuttling practice into the employ of the Confederacy and turned their skills on the Yankees and anyone else who crossed their paths. The bloody saga continued with a new focus.

After the end of the Civil War, the family discovered that while they had no talent for growing corn, they could distill it into some of the finest whiskey in Kentucky. From moonshine the Cahills progressed to the family’s current cash crop, OxyContin. Hillbilly heroin.

The curse came down hard on this current generation. It was seen mainly in accidents but also in mental instability, violent acts, and, in my case, a penchant for dark imaginings, vivid daydreams, fantasies of an only child. Granny Siobhan saw promise in me and was determined that I wouldn’t fall prey to my family’s heritage. She knew that only distance and education could knock such nonsense out of me and save me from the Cahill Curse. To that end, she helped me apply to Amberton Boarding School in Massachusetts. I wrote an essay on

Moby Dick

, blending Melville’s cruel tale with the legends of my own family. It won me a full scholarship.

At fourteen, I left Kentucky on a Greyhound bus. With Granny’s help and an education, I would defy DNA. I would lead a happy, normal life. I, Aine Cahill, would be the exception to the Cahill Curse.

1

The clean scent of the woods pressed me to momentary stillness and I stopped on top of the ridge, inhaling like a woman long imprisoned and finally freed. All around me fallen leaves of red, gold, and orange scuffed my ankles. A few dark evergreens in the distance provided a shaded contrast. Nearby, but hidden from view, was Walden Pond.

How I loved this place. The Massachusetts woods surrounding the gem-like pond had been populated by the great thinkers and writers of the Transcendentalist movement. Ralph Waldo Emerson, Bronson Alcott, and Henry David Thoreau had been my constant companions through graduate school, and now, with more than half of the work for a Ph.D. behind me, I’d come to write my doctoral dissertation in the quiet solitude of Thoreau’s beloved Walden.

The intimacy of the one-room cabin he’d built and lived in for two years, two months, and two days played a vital role in my research and graduate work at Brandeis University. Now I hiked the very ground that had inspired him.

In my imagination, I’d navigated the nearly two miles around the deep blue pond in spring, summer, and fall. Now, while winter bore down and I wrote my doctoral dissertation, I could walk here for real, experiencing the same magic that had held Thoreau. I understood the link between land and writer, the sense of place, the way the seasons dictate thought and development. Thoreau was bound to this land, and by living in his footsteps I too had rooted myself at Walden Pond.

My face was cold as I followed the ridge for half a mile, feet crackling through the leaves. Below me Walden Pond winked blue in a bold shaft of sunlight that brightened the landscape for a fleeting moment, then was consumed by clouds. Late October. A time to celebrate homecoming, and that was exactly what I intended to do. Though I was far from my self-destructive family I felt as if I’d come home. I was all alone, but not lonely.

The upcoming holiday season stretched before me with endless possibilities. Time to read, to research, to write. These activities had become my comfort and close relationships.

“Miss?”

The voice startled me. My feet tangled in the leaves of a dead branch. Before I stumbled, a strong hand grasped my arm.

“Are you lost?”

Before answering, I assessed the man who held my arm. He was tall and lean, dressed in a thick jacket, a hat, gloves, and a holster complete with a weapon. His eyes held easy curiosity. “Who are you?” I sounded rude and suspicious, and I was both. He’d taken me by surprise, and it unsettled me.

He released my arm. “Joe Sinclair. I’m the ranger. Didn’t mean to startle you.” If he had a badge or identification, he didn’t offer to show it.

“The park isn’t closed.” I had a right to wander the woods. I’d come too far, sacrificed too much, to be banned from the place where Thoreau’s essence lingered.

“No, ma’am. The park is open. It’s just we don’t get many visitors this time of year. I wanted to be sure you weren’t stranded or lost.”

“I came because of the isolation.”

“The Thoreau influence.”

“Why, yes.” He’d caught me by surprise yet again. “I’m studying his work.”

“That would explain a lot.”

I couldn’t tell if he was making fun of me or not. “How so?”

“Not many campers or hikers when the cold settles in. I didn’t see a vehicle in the lot, either.” His tone implied a question, though his words did not.