The Secret Life of Salvador Dali (32 page)

Read The Secret Life of Salvador Dali Online

Authors: Salvador Dali

“I did wonderfully well,” I said calmly. And then I added, “But the drawing is even smaller than the first one I made!”

This remark came like a bomb-shell. So did the result of my examination. I was admitted as a student to the School of Fine Arts of Madrid, with this mention, “In spite of the fact that it does not have the dimensions prescribed by the regulations, the drawing is so perfect that it is considered approved by the examining committee.”

My father and sister went back to Figueras, and I remained alone, settled in a very comfortable room in the Students’ Residence, an exclusive place to which it required a certain influence to be admitted, and where the sons of the best Spanish families lived. I launched upon my studies at the Academy with the greatest determination. My life reduced itself strictly to my studies. No longer did I loiter in the streets, or go to the cinema. I stirred only to go from the Students’ Residence to the Academy and back again. Avoiding the groups who foregathered in the Residence I would go straight to my room where I locked myself in and continued my studies. Sunday mornings I went to the Prado and made cubist sketch-plans of the composition of various paintings. The trip from the Academy to the Students’ Residence I always made by streetcar. Thus I spent about one peseta per day, and I stuck to this schedule for several months on end. My relatives, informed of my way of

living by the Director and by the poet Marquina, under whose guardianship I had been left, became worried over my ascetic conduct, which everyone considered monstrous. My father wrote me on several occasions that at my age it was necessary to have some recreation, to take trips, go to the theatre, take walks about town with friends. Nothing availed. From the Academy to my room, from my room to the Academy, and I never exceeded the budget of one peseta per day. My inner life needed nothing else; rather, anything more would have embarrassed me by the intrusion of an unendurable element of displeasure.

In my room I was beginning to paint my first cubist paintings, which were directly and intentionally influenced by Juan Gris. They were almost monochromes. As a reaction against my previous colorist and impressionist periods, the only colors in my palette were white, black, sienna and olive green.

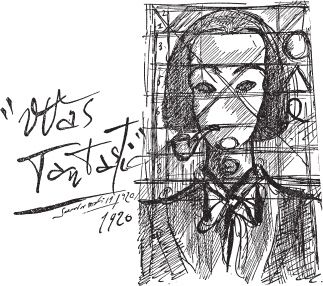

I bought a large black felt hat, and a pipe which I did not smoke and never lighted, but which I kept constantly hanging from the corner of my mouth. I loathed long trousers, and decided to wear short pants with stockings, and sometimes puttees. On rainy days I wore a waterproof cape which I had brought from Figueras, but which was so long that it almost reached the ground. With this waterproof cape I wore the large black hat, from which my hair stuck out like a mane on each side. I realize today that those who knew me at that time do not at all exaggerate when they say that my appearance “was fantastic.” It truly was. Each time I went out or returned to my room, curious groups would form to watch me pass. And I would go my way with head held high, full of pride.

In spite of my generous initial enthusiasm, I was quickly disappointed in the professorial staff of the School of Fine Arts. I immediately understood that those old professors covered with honors and decorations could

teach me nothing. This was not due to their academicism or to their philistine spirit but on the contrary to their progressive spirit, hospitable to every novelty. I was expecting to find limits, rigor, science. I was offered liberty, laziness, approximations! These old professors had recently glimpsed French impressionism through national examples that were chock-full of

tipicismo

(local color)—Sorolla was their god. Thus all was lost.

I was already in full reaction against cubism. They, in order to reach cubism, would have had to live several lives! I would ask anxious, desperate questions of my professor of painting: how to mix my oil and with what, how to obtain a continuous and compact matter, what method to follow to obtain a given effect. My professor would look at me, stupefied by my questions, and answer me with evasive phrases, empty of all meaning.

“My friend,” he would say, “everyone must find his own manner; there are no laws in painting. Interpret—interpret everything, and paint exactly what you see, and above all put your soul into it; it’s temperament, temperament that counts!”

“Temperament,” I thought to myself, sadly, “I could spare you some, my dear professor; but how, in what proportion, should I mix my oil with varnish?”

“Courage, courage,” the professor would repeat. “No details—go to the core of the thing—simplify, simplify—no rules, no constraints. In my class each pupil must work according to his own temperament!”

Professor of painting—professor! Fool that you were. How much time, how many revolutions, how many wars would be needed to bring people back to the supreme reactionary truth that “rigor” is the prime condition of every hierarchy, and that constraint is the very mold of form. Professor of painting—professor! Fool that you were! Always in life my position has been objectively paradoxical—I, who at this time was the only painter in Madrid to understand and execute cubist paintings, was asking the professors for rigor, knowledge, and the most exact science of draughtsmanship, of perspective, of color.

The students considered me a reactionary, an enemy of progress and of liberty. They called themselves revolutionaries and innovators, because all of a sudden they were allowed to paint as they pleased, and because they had just eliminated black from their palettes, calling it dirt, and replacing it with purple! Their most recent discovery was this: everything is made iridescent by light—no black; shadows are purple. But this revolution of impressionism was one which I had thoroughly gone through at the age of twelve, and even at that time I had not committed the elementary error of suppressing black from my palette. A single glance at a small Renoir which I had seen in Barcelona would have been ample for me to understand all this in a second. They would mark time in their dirty, ill digested rainbows for years and years. My God, how stupid people can be!

Everyone made fun of an old professor who was the only one to understand his calling thoroughly, and the only one, besides, possessing a true professional science and conscience. I myself have of ten regretted not having been sufficiently attentive to his counsels. He was very famous in Spain, and his name was José Moreno Carbonero. Certain paintings of his, with scenes drawn from

Don Quixote, I

still enjoy today, even more than before. Don José Moreno Carbonero would come to class wearing a frock coat, a black pearl in his necktie, and would correct our works with white gloves on so as not to dirty his hands. He had only to make two or three rapid strokes with a piece of charcoal to bring a drawing miraculously back on its feet, into composition; he had a pair of sensationally penetrating, photographic little eyes, like Meissonier’s, that are so rare. All the students would wait for him to leave in order to erase his corrections and do the thing over again in their own manner, which was naturally that of “temperament,” of laziness and of pretentiousness without object or glory—mediocre pretentiousness, incapable of stooping to the level of common sense, and equally incapable of rising to the summits of delirious pride. Students of the School of Fine Arts! Fools that you were!

One day I brought to school a little monograph on Georges Braque. No one had ever seen any cubist paintings, and not a single one of my classmates envisaged the possibility of taking that kind of painting seriously. The professor of anatomy, who was much more given to the discipline of scientific methods, heard mention of the book in question, and asked me for it. He confessed that he had never seen paintings of this kind, but he said that one must respect everything one does not understand. Since this has been published in a book, it means that there is something to it. The following morning he had read the preface, and had understood it pretty well; he quoted to me several types of nonfigurative and eminently geometrical representations in the past I told him that this was not exactly the idea, for in cubism there was a very manifest element of representation. The professor spoke to the other professors and all of them began to look upon me as a supernatural being. This kind of attention threatened to reawaken my old childhood exhibitionism, and since they could teach me nothing I was tempted to demonstrate to them in flesh and blood what “personality” is. But in spite of such temptations my conduct continued to be exemplary: never absent from class, always respectful, always working ten times faster and ten times harder at every subject than the best in the class.

But the professors could not bring themselves to look upon me as a “born artist.” “He is very serious,” they said, “he is clever, successful in whatever he sets out to do. But he is cold as ice, his work lacks emotion, he has no personality, he is too cerebral. An intellectual perhaps, but art must come from the heart!” Wait, wait, I always thought deep down within myself, you will soon see what personality is!

The first spark of my personality manifested itself on the day when

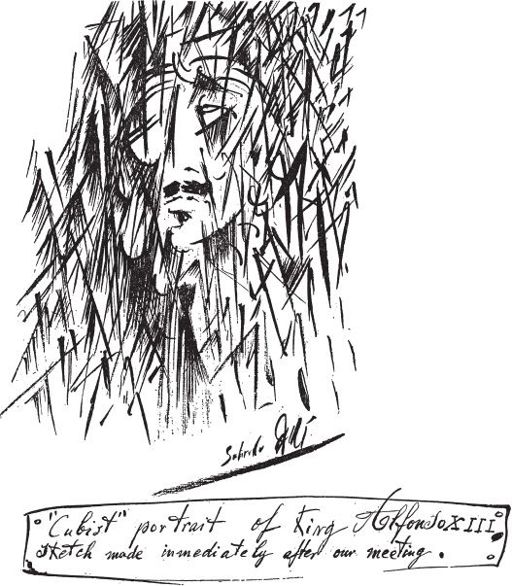

King Alfonso XIII came to pay an official visit to the Royal Academy of Fine Art. Already then the popularity of our monarch was in decline, and the news of his coming visit divided my fellow-students into two camps. Many spoke of not appearing on that day, but the faculty, to forestall any sabotage of the splendor of the occasion, had bluntly announced severe penalties for any failure to be present on that day. One week beforehand there began a thoroughgoing house-cleaning of the Academy, which was transformed from a frightfully run-down state to one that was almost normal. A carefully planned organization was set up to change the aspect of the Royal Academy, and several clever ruses were tried out. In the course of the King’s visit to the different classes the students were to run from one room to the next by some inner stairways and take their places before the King arrived, keeping their backs

to the door, so that he would have the impression that there were many more students than there really were. At that time the school had a very small attendance, and the large rooms always had a deserted look. The authorities also changed the nude models in the life classes—young but very poor creatures, and not much to look at, who were paid starvation wages—for very lovely girls who, I am sure, habitually exercised much more voluptuous professions. They varnished the old paintings, they hung curtains, and decorated the place with many trimmings and green plants.

When everything had been made ready for the comedy that was to be played, the official escort arrived with the King. Instinctively—and were it only to contradict public opinion—I found the figure of our King extremely appealing. His face, which was commonly called degenerate, appeared to me on the contrary to have an authentic aristocratic balance which, with his truculently bred nobility, eclipsed the mediocrity of all his following. He had such a perfect and measured ease in all his movements that one might have taken him for one of Velásquez’s noble figures just come to life.

I felt that he had instantly noticed me among my fellow-students. Because of my hair, my sideburns, and my unique appearance this was not hard to imagine; but something more decisive had just flashed through our two souls. I was considered a representative student and, with some ten of my school-mates who had also been chosen, I was accompanying the King from one class to another. Each time I entered a new class and recognized the backs of the students whom we had just left and who were now busily working I was devoured by a mortal shame at the thought that the King might discover the comedy that was being played for his benefit. I saw these students laugh while they were still buttoning up their jackets, into which they had hurriedly changed while the Director of the School detained the King for a moment to have him admire an old picture and thereby gain a little time. Several times I was tempted to cry out and denounce the deception that was being practiced on him, but I managed to control my impulse. Nevertheless my agitation kept growing as we visited one room after another, and knowing myself as I did, I kept constantly repeating to myself, “Look out, Dali, look out! Something phenomenal is about to happen!”