The Secret History of Extraterrestrials: Advanced Technology and the Coming New Race (15 page)

Read The Secret History of Extraterrestrials: Advanced Technology and the Coming New Race Online

Authors: Len Kasten

Tags: #UFOs/Paranormal

12

Sci-Fi Film

A Path to Self-Discovery

Was it synchronicity that brought me to Los Angeles that Wednesday before Memorial Day in 1977? Searching for a movie to see that evening, my friends and I settled on the premiere that night of a new sci-fi film called

Star Wars

at Grauman’s Chinese Theater in Hollywood. A long-time sci-fi fan, I didn’t expect much of this movie since no decent science-fiction fare had appeared on the screen since

2001: A Space Odyssey

nine years earlier in 1968. But it turned out to be a memorable experience. It was the first (and last) time in my life that I ever witnessed an entire movie audience stand up and cheer as the credits rolled. The rest, as they say, is history.

Little did I realize then that I was a witness to that history. An amateur sociologist by instinct, I have puzzled over that spontaneous eruption of audience appreciation and delight many times over the years. Now, thirty years later, I finally think I understand it. But let’s start at the beginning.

VISUAL TRICKS AND FANTASTIC VOYAGES

It all started with an accident. In Paris in early 1897, a stage magician turned moviemaker named Georges Méliès was filming a street scene in front of the Paris Opera when the camera jammed, as they frequently did in the early days. Naturally, the continuity of the film was briefly interrupted. As recounted by Carlos Clarens in his classic book

An Illustrated History of Horror and Science-Fiction Films,

“When he reviewed the developed film later on, Méliès was astounded to see a bus changed into a hearse. Film had stopped while time had not. This wonderfully macabre metamorphosis was the genesis of all film trickery. The Fantastic Film had been born.”

Movie poster from 1977 for

Star Wars

Méliès quickly realized the possibilities and began to develop techniques that allowed him to give free rein to his imagination. He promised to bring to his audiences “visual tricks, and fantastic voyages.” To accomplish this, he built the first movie studio in the world in the Paris suburb of Montreuil. It had glass walls and ceilings and was equipped with all sorts of stage contrivances to facilitate trick photography. Says Clarens, “To Méliès the camera became a machine to register the world of dreams and the supernatural, the mirror to enter Wonderland.” He became known as the King of Fantasmagoria, the Jules Verne of the Cinema, and the Magician of the Screen.

After breaking new cinematic ground with such imaginative productions as

The Battleship Maine, The Man with Four Heads, She,

and

Cinderella,

all under thirty minutes long, Méliès created his grandest production, widely considered to be his masterpiece. In 1902, at the very dawning of the twentieth century, Méliès became the father of science-fiction movies with his film

A Trip to the Moon.

Based on Jules Verne’s

From the Earth to the Moon

and H. G. Wells’s

First Men in the Moon

and also thirty minutes in length, the movie followed a scientific expedition to the moon and back. Clarens says, “It is, then, the movies’ first venture into science-fiction and interplanetary travel . . . As the rocket is fired from the giant cannon atop the Paris roofs, the film cuts to the spaceship (in miniature) traveling against a painted backdrop of the sky, then cuts to the moon from viewpoint of the cosmonauts, getting larger and larger, and finally there is a cut or fast dissolve to the moon’s face wincing in pain as the bulletlike ship enters the eye.”

From its very inception, the science-fiction genre enthralled audiences. The film was an instant success. Bootleg copies were made from the three prints Méliès sent to his American agents and were shown all over the United States. While the books of Verne and Wells had also been very successful, the film brought a wider audience into the sci-fi fold because it was visual and could appeal to those who were not fond of literature and were not capable of appreciating literary nuance. Like fast food for the imagination, science-fiction film opened the world of the future to the masses. Most importantly, the writings of both men, but especially Verne, portrayed the man of the future as a conqueror of space and the ocean depths, expanding his dominion through science to previously forbidding places.

The Time Machine

by Wells extended human reach through time into the future. This was a hopeful and inspiring message for humanity and had a powerful spiritual appeal to fin de siècle audiences.

After this hopeful beginning, sci-fi film got lost in the shuffle as the world became embroiled in war and economic depression. By the end of World War II, there was very little to suggest that the human race could ever aspire to the glorious dreams of Verne, Wells, and Méliès. In fact, with the advent of the atomic bomb, it appeared that scientific advancement had simply given us more efficient means of slaughtering each other. Then, as we entered the second half of the century, everything changed. Spacecraft from other stars appeared in our skies and crashed in our deserts, and spacemen had encounters and conversations with humans. By their presence, the aliens proved that space travel was possible and that perhaps science could save us after all. And so the dream was revived, and a new and powerful impetus was given to science-fiction literature and film.

GORT! KLAATU BARADA NIKTO

The resurrection of sci-fi film in the 1950s was startling in terms of both quantity and diversity. Films belonging to this genre, however loosely, numbered in the hundreds over the course of the decade, and most of them were profitable. It started off appropriately and auspiciously. The first important entry out of the gate was

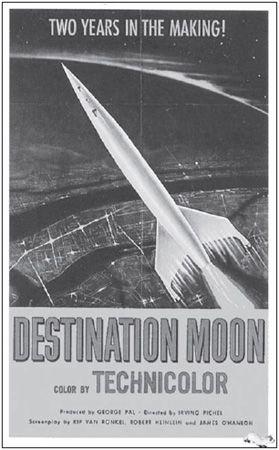

Destination Moon,

produced in 1950 by George Pal and based on the youth novel

Rocketship Galileo

by Robert Heinlein, who also wrote the original screenplay.

Taking up where Méliès had left off fifty years previously, this film depicted a moon journey as scientifically realistic as possible. Director Irving Pichel consulted with physicists and astronomers, including German rocket expert Hermann Oberth, and employed famed astronomy painter Chesley Bonestell for set design. It took one hundred men two months to build the realistic moonscape set, which brought it the 1950 Oscar for special effects. This movie turned out to be remarkably predictive of the actual moon landing in 1969.

Destination Moon

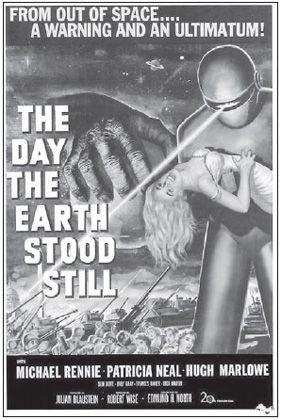

was followed, in 1951, by a movie that is now widely considered to be the best American sci-fi movie of the fifties,

The Day the Earth Stood Still.

What made this film so unusual was the fact that it succeeded on several levels. The dramatic story line and love story were intriguing and gripping, but it also got away with committing what is considered the unpardonable sin in Hollywood—exhorting the audience with a message. An alien called Klaatu comes to earth in a flying saucer as an envoy from the “planetary federation” to warn us about the use of nuclear weapons and gives a long speech about our fate if we ignore the warning. On a third level, it is a Christian allegory, since Klaatu is killed by the military but then is resurrected by his robot, Gort, and at the end ascends Christlike to the skies in his spaceship. It was directed by Robert Wise, who later directed

The Andromeda Strain

and

Star Trek: The Motion Picture.

Movie poster from 1950 for

Destination Moon

Some other noteworthy films from 1951 based on interplanetary drama were

Flight to Mars, Rocketship X-M, Flying Disc Man from Mars,

and

The Man from Planet X.

CAT WOMEN OF THE MOON

Up to this point, filmmakers traded in likely scientific advancement that would lead to space travel. Although fantastic, it was all believable because faith in science had been restored, and it all seemed possible, even before Sputnik. This was pure science fiction, and the science-fiction writers wrote for and applauded these films. The aliens were all humanlike and civilized. Then, things took a “horrible” turn. Succumbing to the popular appetite for horror films, Hollywood decided to populate the universe with monsters. The turning point was the Howard Hawks production

The Thing,

released in late 1951, in which the threatening alien feels “no pleasure, no pain . . . no emotion.” It just wants to survive and procreate.

Movie poster from 1951 for

The Day the Earth Stood Still

The Thing

started the whole monster cycle of sci-fi movies, largely dominated by directors such as Roger Corman. The respected science-fiction writers of the fifties were appalled at this turn of events. They were especially enraged by the way scientists now became “mad scientists,” a throwback to Dr. Frankenstein in the thirties.

The Thing

was a well-made film and was financially successful. This success further emboldened the “monster sci-fi” moviemakers. Some notable films in this subgenre were

The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms,

which was the first project of Ray Harryhausen, who went on to legendary animation fame,

Invaders from Mars, Robot Monster,

and

Cat Women of the Moon

(all in 1953),

Them

in 1954,

This Island Earth

in 1955, and the still-famous

Invasion of the Body Snatchers

in 1956.

By 1959, a very clear dichotomy between two different types of scifi films had become evident. On the one hand, there were the films that honestly sought to capture the drama and excitement engendered by the possibilities of space exploration, time travel, and interaction with extraterrestrials. These mainstream science-fiction films tried to adhere to likely future scientific developments and the implications thereof. The two men most identified with this pseudodocumentary style were producer George Pal and director Robert Wise. After

Destination Moon,

Pal went on to make

When Worlds Collide

in 1952,

War of the Worlds

and

Conquest of Space,

both in 1954, and the H. G. Wells classic,

The Time Machine,

in 1960. All these films had the stamp of a visionary. Hollywood producer Paul Davids, who knew Pal well, says in a biographical essay about the legendary director, still available in his archived column “Flying Saucers Over Hollywood” on the website

www.alienzoo.com

, “George Pal began to understand that humankind’s ultimate destiny could only be fulfilled by people freeing themselves from planet Earth and venturing into space, to the planets.” On the other hand, the monster movies were patently absurd, simply substituting space monsters for the more earthbound variety. These movies worked very well, and they made money. They attracted the audiences who might otherwise choose some other type of horror movie, and so they really belonged more properly in the horror genre.

The fact that so many of the spacecraft in the sci-fi films in the 1950s were saucerlike clearly establishes the link between the profusion of movies in this genre and the reports of UFO sightings coming in from all over the world during that decade. Since it is now well known that the military clamped a tight lid of secrecy on all UFO-related reports in the fifties, it is not much of a stretch to assume that they sought to use Hollywood to further their aims of deception, obfuscation, and disinformation. Author Bruce Rux, in his book

Hollywood Vs. the Aliens: The Motion Picture Industry’s Participation in UFO Disinformation,

makes an excellent case for the likelihood that the intelligence agencies influenced Hollywood producers to make the aliens so monstrous and ridiculous that the public would cease to take the phenomena seriously. This ploy worked so well that even today you are likely to get a snicker if you bring up the subject of UFOs or extraterrestrials in any politically correct environment.