The Seamstress

A Novel

To the women

—living and dead—

of my family,

all of them

ladies and

guerreiras

And to James,

who always believed

…rising toward a saint

still honored in these parts,

the paper chambers flush and fill with light

that comes and goes, like hearts…

receding, dwindling, solemnly

and steadily forsaking us,

or, in the downdraft from a peak,

suddenly turning dangerous…

—Elizabeth Bishop, “The Armadillo”

E

mília awoke alone. She lay in the massive antique that had once been her mother-in-law’s bridal bed and was now her own. It was the color of burnt sugar with clusters of cashew fruits carved into its giant head-and footboard. The meaty, bell-shaped fruits that emerged from the jacarandá wood looked so smooth and real that, on her first few evenings in this bed, Emília had imagined them ripening overnight—their wooden skins turning pink and yellow, their solid meat becoming soft and fragrant by morning. By the end of her first year in the Coelho house, Emília had given up such childish imaginings.

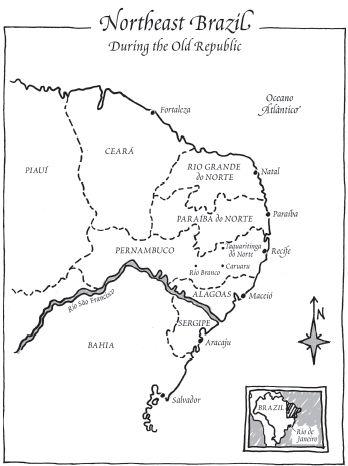

Outside, it was dark. The street was quiet. The Coelho family’s white house was the largest of all of the newly built estates on Rua Real da Torre, a recently paved road that stretched from the old Capunga Bridge and out into unclaimed swampland. Emília always woke before sunrise, before peddlers invaded Recife’s streets with their creaking carts and their voices that rose to her window like the calls of strange birds. In her old home in the countryside, she’d been accustomed to waking up to roosters, to her aunt Sofia’s whispered prayers, and most of all, to her sister Luzia’s breath, even and hot against her shoulder. As a girl, Emília had disliked sharing a bed with her sister. Luzia was too tall; she kicked open the mosquito net with her long legs. She stole the covers. Their aunt Sofia couldn’t afford to buy them separate beds and insisted it was good to have a sleeping companion—it would teach the girls to occupy little space, to move gently, to sleep silently, preparing them to be good wives.

In the first days of her marriage, Emília had kept to her side of the bed, afraid to move. Degas complained that her skin was too warm, her breathing too loud, her feet too cold. After a week, he’d moved across the hall, back to the snug sheets and narrow mattress of his childhood bed. Emília quickly learned to sleep alone, to sprawl, to take up space. Only one male shared her room and he slept in the corner, in a crib that was quickly becoming too small to hold his growing body. At three years of age, Expedito’s hands and feet nearly touched the crib’s wooden bars. One day, Emília hoped, he would have a real bed in his own room, but not here. Not while they lived in the Coelhos’ house.

The sun rose and the sky lightened. Emília heard shouting in the streets. Six years before, on her first morning in the Coelho house, Emília had trembled and held the bedsheet to her chest until she realized the voices outside the gates were not intruders. They were not calling her name, but the names of fruits and vegetables, baskets and brooms. Each Carnaval, the peddlers’ voices were replaced by the thunderous beating of maracatu drums and the drunken shouts of revelers. Five years earlier, during the first week of October, the peddlers had disappeared completely. Throughout Brazil there were gunshots and calls for a new president. By the next year, things had calmed. The government had changed hands. The peddlers returned.

Emília now found comfort in their voices. The men and women sang the names of their wares: “Oranges! Brooms! Alpercata sandals! Belts! Brushes! Needles!” Their voices were strong and cheerful, a relief from the whispers Emília had endured all week. A long, black ribbon hung from the bell attached to the Coelhos’ iron gate. The ribbon warned neighbors, the milkman, the ice wagon, and all delivery boys dropping off flowers and black-bordered condolence cards that this was a house in mourning. The family inside was nurturing its grief, and should not be disturbed by loud noises or unnecessary visits. Those who rang the bell did so tentatively. Some clapped to announce their presence, afraid to touch the black ribbon. The peddlers ignored it. They shouted over the fence, their voices carrying past the massive metal gate, through the Coelho house’s drawn curtains, and into its dark hallways. “Soap! String! Flour! Thread!” The peddlers didn’t concern themselves with death; even grieving people needed the things the peddlers sold, the small necessities of life.

Emília rose from bed.

She slipped a dress over her head but didn’t zip it; the noise might wake Expedito. He lay diagonally across his crib, safely beneath mosquito netting. His forehead shone with sweat. His mouth was set in a tight line. Even in sleep he was a serious child. He’d been that way as an infant, when Emília had discovered him. He’d been skinny and covered in dust. “A foundling,” the maids called him. “A child of the backlands.” He was born there during the infamous drought of 1932. It was impossible that he would remember his real mother, or those first hard months of his life, but sometimes, when Expedito stared at Emília with his dark, deep-set eyes, he had the stern and knowing look of an old man. Since the funeral he’d often looked at Emília in this way, as if reminding her that they should not linger in the Coelho house. They should travel back to the countryside, for his sake as well as hers. They should deliver a warning. They should fulfill their promise.

Emília felt a pinch in her chest. All week she’d felt as if there was a rope within her, stretched from her feet to her head and knotted at her heart. The longer she remained in the Coelho house, the more the knot tightened.

She left the room and zipped up her dress. The fabric gave off a sharp, metallic smell. It had been soaked in a vat of black dye and then dipped in vinegar, to set the new color. The dress had been light blue. It was cut in a modern style with soft, fluttering sleeves and a slim skirt. Emília had been a trendsetter. Now all of her solid-colored dresses were dyed black and her patterned ones packed away until her year of mourning was officially over. Emília had hidden three dresses and three bolero jackets in a suitcase under her bed. The jackets were heavy; each had a thick wad of bills sewn into its satin lining. Emília had also packed a tiny valise with Expedito’s clothing, shoes, and toys. When they escaped from the Coelho house, she’d have to carry the bags herself. Knowing this, she’d packed only necessities. Before her marriage, Emília had placed too much stock in luxuries. She’d believed that fine possessions had the power to transform; that owning a stylish dress, a gas stove, a tiled kitchen, or an automobile would erase her origins. Such possessions, Emília had thought, would make people look past the calluses on her hands or her rough country manners, and see a lady. After her marriage and her arrival in Recife, Emília discovered this wasn’t true.

Halfway downstairs, she smelled funeral wreaths. The round floral arrangements cluttered the foyer and front hallway. Some were as small as plates, others so large they sat on wooden easels. All were tightly packed with white and purple flowers—gardenias, violets, lilies, roses—and had dark ribbons pinned across their empty centers. Scrawled across the ribbons, painted in gold ink, were the senders’ names and consoling phrases: “Our Deepest Sympathies,” “Our Prayers Are with You.” The older wreaths were limp, their gardenias yellowed, their lilies shriveled. They gave off a tangy, putrid smell. The air was thick with it.

Emília held the staircase banister. Four weeks ago her husband, Degas, had sat with her on those marble steps. He’d tried to warn her, but she hadn’t listened; Degas had tricked her too many times before. Since his death, Emília spent her days and nights wondering if Degas’ warning hadn’t been a trick at all, but a final attempt at redemption.

Emília walked into the front hall. There was a new wreath, its lilies rigid and thick, their stamens heavy with orange pollen. Emília pitied those lilies. They had no roots, no soil, no way of sustaining themselves, and yet they bloomed. They acted as if they were still fecund and strong when really they were already dead—they just didn’t know it. Emília felt the knot in her chest tighten. Her instincts said Degas had been right, his warning a valid one. And she was like those condolence wreaths, giving him the recognition he so desperately wanted in life but only received in death.

The funeral wreath was a rite unique to Recife. In the countryside it was often too dry to grow flowers. People who died during the rainy months were both blessed and cursed: their bodies decayed faster, and mourners had to pinch their noses during wakes, but there were dahlias, rooster’s crest, and Beneditas bunched into thick bouquets and placed inside the deceased’s funeral hammock before it was carried to town. Emília had attended many funerals. Among them was her mother’s, which she could barely remember. Her father’s funeral occurred later, when Emília was fourteen and Luzia twelve. They lived with their aunt Sofia after that, and though Emília loved her aunt, she couldn’t wait to run away, to live in the capital. As a girl, Emília had always believed that she would leave Sofia and Luzia. Instead, they’d left her.

Emília slipped a black-bordered card from the newest wreath. It was addressed to her father-in-law, Dr. Duarte Coelho.

“Grief cannot be measured,” the card said. “Neither can our esteem for you. Come back to work soon! From: Your colleagues at the Criminology Institute.” The wreaths and cards weren’t meant for Degas. The gifts that arrived at the Coelho house were sent to curry favor with the living. Most of the floral arrangements were from politicians, or from Green Party compatriots, or from underlings in Dr. Duarte’s Criminology Institute. A few of the wreaths were from society women hoping to be in Emília’s good graces. The women had been customers in Emília’s dress shop. They hoped her mourning wouldn’t stifle her dressmaking hobby. Respectable women didn’t have careers, so Emília’s thriving dress shop was considered a diversion, like crochet or charity work. Emília and her sister had been seamstresses. In the countryside, their profession was highly regarded, but in Recife this tier of respectability didn’t exist—a seamstress was the same as a maid or a washerwoman. And to the Coelhos’ dismay, their son had taken up with one. According to the Coelhos, Emília had two saving graces: she was pretty and she had no family. There wouldn’t be parents or siblings clapping at the front gate and asking for handouts. Dr. Duarte and his wife, Dona Dulce, knew Emília had a sister but believed that she—like Emília’s parents and her aunt Sofia—had died. Emília didn’t contradict this belief. As seamstresses, both she and Luzia knew how to cut, how to mend, and how to conceal.

“A great seamstress must be brave.” This was what Aunt Sofia used to say. For a long time, Emília disagreed. She believed that bravery involved risk. With sewing, everything was measured, traced, tried on, and revised. The only risk was error.

A good seamstress took exact measurements and then, using a sharp pencil, transferred those measurements onto paper. She traced the paper pattern onto cheap muslin, cut out the pieces, and sewed them into a sample garment that her client tried on and which she—the seamstress—pinned and remeasured to correct the flaws in her pattern. The muslin always looked bland and unappealing. At this point, the seamstress had to be enthusiastic, envisioning the garment in a beautiful fabric and convincing the client of her vision. From the pins and markings on the muslin, she revised the paper pattern and traced it onto good fabric: silk, fine-woven linen, or sturdy cotton. Next, she cut. Finally, she sewed those pieces together, ironing after each step in order to have crisp lines and straight seams. There was no bravery in this. There was only patience and meticulousness.

Luzia never made muslins or patterns. She traced her measurements directly onto the final fabric and cut. In Emília’s eyes this wasn’t bravery either—it was skill. Luzia was good at measuring people. She knew exactly where to wind a tape around arms and waists in order to get the most accurate dimensions. But her skill wasn’t dependent on accuracy; Luzia saw beyond numbers. She knew that numbers could lie. Aunt Sofia had taught them that the human body had no straight lines. The measuring tape could miscalculate the curve of a slumped back, the arc of a shoulder, the dip of a waist, the bend of an elbow. Luzia and Emília were taught to be wary of measuring tapes. “Don’t trust a strange tape!” their aunt Sofia often yelled at them. “Trust your own eyes!” So Emília and Luzia learned to see where a garment had to be taken in, let out, lengthened or shortened before they’d even unrolled their measuring tapes. Sewing was a language, their aunt said. It was the language of shapes. A good seamstress could envision a garment encircling a body and see the same garment laid flat on a cutting table, broken into its individual pieces. One rarely resembled the other. When laid flat, the pieces of a garment were odd shapes broken into two halves. Every piece had its opposite, its mirror image.

Unlike Luzia, Emília preferred making paper patterns. She wasn’t as confident at measurement and felt nervous each time she took up her scissors and sliced the final cloth. Cutting was unforgiving. If the pieces of a garment were cut incorrectly, it meant hours of work at the sewing machine. Often these hours were futile—there were some mistakes sewing could never fix.

Emília replaced the condolence card. She walked past the funeral wreaths. At the end of the entrance hall was an easel without flowers propped upon it. Instead, there was a portrait. The Coelhos had commissioned an oil painting for their son’s wake. The Capibaribe River was deep and its currents strong, but police had managed to find Degas’ body. It had been too bloated to have an open casket during the wake, so Dr. Duarte had a portrait of his son made instead. In the portrait, Emília’s husband was smiling, thin, and confident—all of the things he’d never been in life. The only aspect the painter had gotten right was Degas’ hands. They had tapered fingers and buffed, immaculate nails. Degas had been stout, with a thick neck and wide fleshy arms, but his hands were slender, almost womanly. Emília wished she’d noticed this the minute she’d met him.

Police deemed Degas’ death an accident. The officers were loyal to Dr. Duarte because he’d founded the state’s first Criminology Institute. Recife, however, was a city that prized scandal. Accidents were dull, blame interesting. During the wake, Emília had heard mourners whispering. They tried to root out the responsible parties: the car, the rainstorm, the slick bridge, the rough waters of the river, or Degas himself, alone at the wheel of his Chrysler Imperial. Dona Dulce—Emília’s mother-in-law—insisted on the police’s version of events. She knew that her son had lied, saying he was going to his office to pick up papers related to an upcoming business trip, the first such trip Degas had ever taken. He never went to his office. Instead he drove aimlessly around the city. Dona Dulce did not blame Emília for Degas’ death; she blamed her daughter-in-law for the aimlessness that had caused it. A proper wife—a well-bred city girl—would have cured Degas’ weaknesses and given him a child. Dr. Duarte was more sympathetic toward Emília. Her father-in-law had arranged Degas’ so-called business trip. Without Dona Dulce’s knowledge, Dr. Duarte had reserved a spot for their son at the prestigious Pinel Sanitorium in São Paulo. Dr. Duarte had believed that the clinic’s electric baths would accomplish what marriage and self-discipline had not.