The Sea Glass Sisters (8 page)

Read The Sea Glass Sisters Online

Authors: Lisa Wingate

The ferry landing is teeming with people. Red Cross trucks, National Guard caravans, and groups of aid workers in identifying vests or T-shirts exit the ferry in droves. Meanwhile, visitors who underanticipated the effects of the storm and residents who have decided to relocate to the mainland until things get better line up to shuffle their way onto the outgoing boat. Ferry attendants encourage everyone to be patient. The emergency transports are operating on a regular schedule, despite issues with shoaling and debris left behind by the storm. The commute across the water, two and a half hours under normal circumstances, will be slower than usual.

Arduous is what it will be. We have no idea of Aunt Sandy’s condition. By now she has, hopefully, arrived at the hospital by helicopter and is in the hands of cardiac doctors and nurses. The Shell Shop friends have left their digging out in order to accompany us to the landing, as have members of Aunt Sandy’s church and Bible study group. We’ve gathered in a circle, joined hands, and prayed.

We hug and say our good-byes, and the ferry worker who was kind enough to move Mom and me to the front of the line escorts us on. There’s no room for the rest of the Sisterhood of the Shell Shop to go. This ferry is full, and the wait right now is several hours.

“Let us know as soon as you hear anything!” Teresa yells.

We promise that we will, and then the crowd of weary, tired people closes in around us. I suddenly realize how much we all look alike in this condition. How completely desperation can equalize people.

It’ll probably be a couple hours before we’re close enough to the mainland to pick up a working cell tower and find out more about the medevac flight and Aunt Sandy’s condition. We’re fortunate that everything fell into place for her to be taken off the island so quickly, but even with the fast response, there’s danger of a bad outcome. We know that. With a thready pulse and rising and falling from consciousness, she needed a top-notch cardiac team, sooner rather than later.

A man gives up his spot near the cabin wall, and Mom sits down, but I can’t. I stand at the deck railing, hang over it, trying to let the sea breeze take away the feeling that I might throw up. Not far away, the pelicans swirl over the debris-littered surf, enjoying the buffet of floating treats offered courtesy of the storm. They seem to promise that all will eventually return to normal. The storm churns up food. The birds feast. Something good comes of even the worst events.

Is it possible?

I wonder.

I watch the water slide by, and I do that thing I’ve mostly left out of my life these past few years, in favor of covering all the other bases. I pray and pray and pray . . .

I lose track of time. Maybe I doze off, standing there. I’m not sure. The adrenaline seeps out of my body, bit by bit, and I’m boneless and weary.

A guy I’ve never seen before hands me a protein bar and a bottle of water. “Here,” he says, smiling at me. He can’t be over twenty years old. Not that much further along in life than my own kids. A laid-back beach bum type. “They were handing them out from a Walmart truck. I figured if I took it, I’d come across someone who needed it. That’s how it rolls, right?”

I nod and thank him and take the gift.

I figured if I took it, I’d come across someone who needed it.

The wisdom of that strikes me in a new way.

I think of those weekends of advanced emergency training given to me by the county over the years. Of the relatives and friends who watched my children so I could go. The Red Cross volunteer who taught the classes. My long-ago high school health teacher who tested all the students to see who could react in a disaster. That teacher encouraged me to pursue something in the medical field, maybe think about becoming a doctor. When Robert and I made an immature decision on prom night and ended up coping with pregnancy, marriage, and the financial implications, that teacher helped me get into the 911 dispatcher training program with the county. Big dreams became smaller dreams, and life went on.

Sinking down against the railing, I rest my head and think of Aunt Sandy’s advice to me about starting off on a new adventure in the second half of life. It comes back now, that long-ago dream of becoming a doctor. The idea resurfaces, dull and moss-covered, like something that’s been trapped underwater for years. I pull it out, wipe it off, look at it from several angles, and think . . .

maybe

. . .

Could it be time now? Is this the time to reinvent?

Is survival sometimes about death and rebirth? Egg to caterpillar to chrysalis to butterfly? Is this, this ending of our family as I know it, not the death season but the birth of the butterfly season?

If a woman who’s never owned a shop or lived by the sea can become Sandy of Sandy’s Seashell Shop, what can I do?

If . . .

when

Aunt Sandy makes it through this scare, I won’t try to persuade her to give up the Seashell Shop and move home, where the family can monitor and supervise and babysit her. A butterfly should live as long as it can in its natural habitat. This place of sand and water, of seasons and storms and challenges, has become who she is.

The thoughts seep through me, percolate like water through coffee grounds, producing something new, thick with tantalizing aroma. What would Robert say if I suggested all this? What would the kids think?

You’re not the only ones heading off to school. Mom’s got plans. . . .

I close my eyes and let the thought drift like a raft just floating wherever the current will take it. I doze and wake and feel the water swaying beneath me.

I’m surprised when I finally climb to my feet and we’re within sight of land. I remember my phone and pull it out, but then I turn and catch a glimpse of Mom standing on her bench. She’s already on her cell, waving at me, trying to give me the high sign.

I let out the breath I have been holding. The news must be good.

My phone chimes as the texts from the past few days rush in. There’s Jessica in a cheerleading photo, smiling alongside the friend she’d been fighting with.

Miss you, Mom!

the message says underneath. Micah reports that he’s pulled a B on his first calculus test. Robert must have made him send the text—Micah would never do that on his own. There’s a note from Robert, offering the rundown of activities around home.

Knew you’d be wondering,

it says.

Another from Uncle Butch, several days old. He’s worried about his sisters after the storm. He wants someone to send him more information. How dare the cell service not do his bidding. This is ridiculous. He just wants to know that everyone’s all right, for heaven’s sake.

Beneath that, Carol has sent an update, written during the graveyard shift as my mother, Aunt Sandy, and I huddled together through the heart of the storm.

TOD 6 hr b4 call-in. 10W mom and boyfriend. Wanted u 2 know.

I close my eyes, take in a breath of salt and sand and driftwood drying in the sun. Tears squeeze out and trail along my skin, the breeze cooling the heat of sorrow. Little Emily was gone from this world six hours before her mother called 911. A bedtime battle, perhaps—that terrible hour of the evening when unstable homes erupt and unspeakable things happen. A plot by the mother and her boyfriend to stage a kidnapping to cover it up. Little girls should be safe in this world, in their own homes, but the fact is that sometimes they’re not. By now that felony warrant for the mother and the live-in boyfriend has been executed. The baby still strapped in Trista’s car that night is somewhere safe. Even though I ache with this news, there is that much to be thankful for.

Emily is safe now as well. I know it. She isn’t cold or alone or hungry. She is not lost in the woods, running wildly as in my dreams. Seeking rescue.

She is home.

All around her, there is nothing but love.

A hand touches my shoulder, and I jump, then realize that Mom has pushed her way through the crowd to me. The lines have loosened around her eyes, and her brows have relaxed a little. “She made it there in good shape. They were able to clear the blockages with an emergency angioplasty and stents. They may do bypass surgery later, after she’s had time to get better, but she’s stable now and in recovery.”

My mother stretches out her arms, and we fold together and cry and rock and breathe. I don’t close my eyes but instead watch the sun specks through a watery rim of emotion. But for the floating debris, Pamlico Sound is beautiful today. A pod of dolphins plays in the distance. They seem jovial and untroubled, as if they’re saying,

What storm? It’s over. Let it go. Let’s celebrate life.

Mom finally releases me, then gives me a serious look. “I’m not going home after Sandy’s surgery. I’m staying, and I don’t know for how long. I already called and talked to George about it. Sandy needs someone to make her take care of herself the way she should, at least while she heals up.” But there’s something in her voice that tells me this relocation may be more than temporary.

I feel a sting of separation. As much as our rough edges may rub blisters on each other from time to time, my mother and I have never been more than a few miles apart since the Piggly Wiggly years. Now she will be halfway across the country.

I bite back a sudden wave of insecurity and the bleak but selfish thought that she will miss all the kids’ senior-year milestones.

“I think you should.” I have to force myself to say it.

“But I’ll be home for all the kids’ things. As many as I can catch.” She reads my mind the way mothers and daughters do. “I have frequent-flier miles.”

“The school will miss having you for all those volunteer hours.” I’m searching for something innocuous that won’t stir up more emotion. I know this is the right thing for my mother, and I don’t want to mess it up.

She flips a hand in the air, swatting a man behind her, then turning to apologize before answering me. “Phooey on that school system. They should have appreciated me while they had me.”

Her answer leaves me dumbfounded. This is the first time I’ve heard her actually let it go, not rehash all the reasons it was wrong for the district superintendent to make staffing decisions based on age and gender rather than years of experience.

Another milestone. Maybe we are both stretching our wings. Maybe this is a butterfly season for both of us.

Perhaps this rebirth from one thing to another happens repeatedly in a lifetime. Maybe life is a series of little deaths and rebirths, of passages and rites of passage, of God teaching you to stop clinging to one thing so you can reach for another.

A death grip doesn’t reach very well.

I think of that tiny woman in her big white house in Fairhope. Aunt Sandy’s friend, Iola Anne Poole—ninety-one years old, yet still surviving on these shifting bars of sand.

What she said makes sense now, as I stand shoulder-to-shoulder with my mother and watch the dolphins play in the sunlit water.

The storms come and it’s water and wind as far as the eye can see for a bit. But winds calm and the waters drain. We find our feet again, and the ground under us sprouts a new crop of seed. That is always the way of it.

I don’t suppose this storm will be any different.

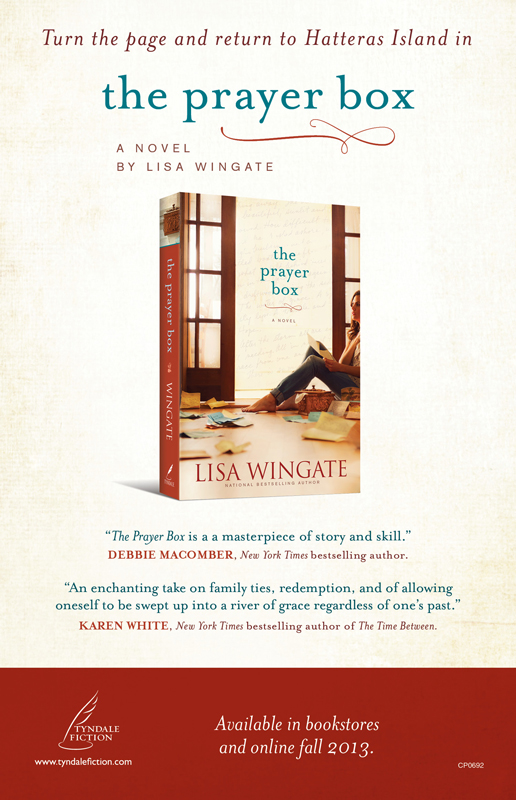

Lisa Wingate is a former journalist, speaker, and the author of twenty novels, including the national bestseller

Tending Roses

, now in its eighteenth printing. She is a seven-time ACFW Carol Award nominee, a Christy Award nominee, and a two-time Carol Award winner. Her novel

Blue Moon Bay

was a Booklist Top Ten of 2012 pick. Recently the group Americans for More Civility, a kindness watchdog organization, selected Lisa along with Bill Ford, Camille Cosby, and six others as recipients of the National Civies Award, which celebrates public figures who work to promote greater kindness and civility in American life. When not dreaming up stories, Lisa spends time on the road as a motivational speaker. Via Internet, she shares with readers as far away as India, where

Tending Roses

has been used to promote women’s literacy, and as close to home as Tulsa, Oklahoma, where the county library system has used

Tending Roses

to help volunteers teach adults to read.

Lisa lives on a ranch in Texas, where she spoils the livestock, raises boys, and teaches Sunday school to high school seniors. She was inspired to become a writer by a first-grade teacher who said she expected to see Lisa’s name in a magazine one day. Lisa also entertained childhood dreams of being an Olympic gymnast and winning the National Finals Rodeo but was stalled by the inability to do a backflip on the balance beam and parents who wouldn’t finance a rodeo career. She was lucky enough to marry into a big family of cowboys and Southern storytellers who would inspire any lover of tall tales and interesting yet profound characters. She is a full-time writer and pens inspirational fiction for both the general and Christian markets. Of all the things she loves about her job, she loves connecting with people, both real and imaginary, the most. More information about Lisa’s novels can be found at

www.lisawingate.com

.