The Sea Around Us (21 page)

Authors: Rachel Carson

The Antarctic Ocean, being merely a continuous band of water encircling the globe, is another exception to the typical current pattern. Its waters are driven constantly into the east and the northeast by winds from the west and southwest, and the currents are given speed by the quantities of fresh water pouring in from melting ice. It is not a closed circulation; water is given off, in surface currents and by deep paths, to the adjacent oceans, and in return other water is received from them.

It is in the Atlantic and Pacific that we see most clearly the interplay of cosmic forces producing the planetary currents.

Perhaps because of the long centuries over which the Atlantic has been crossed and recrossed by trade routes, its currents have been longest known to seafaring men and best studied by oceanographers. The strongly running Equatorial Currrents were familiar to generations of seamen in the days of sail. So determined was their set to westward that vessels intending to pass down into the South Atlantic could make no headway unless they had gained the necessary easting in the region of the southeast trades. Ponce de Leon's three ships, sailing south from Cape Canaveral to Tortugas in 1513, sometimes were unable to stem the Gulf Stream, and âalthough they had great wind, they could not proceed forward, but backward.' A few years later Spanish shipmasters learned to take advantage of the currents, sailing westward in the Equatorial Current, but returning home via the Gulf Stream as far as Cape Hatteras, whence they launched out into the open Atlantic.

The first chart of the Gulf Stream was prepared about 1769 under the direction of Benjamin Franklin while he was Deputy Postmaster General of the Colonies. The Board of Customs in Boston had complained that the mail packets coming from England took two weeks longer to make the westward crossing than did the Rhode Island merchant ships. Franklin, perplexed, took the problem to a Nantucket sea captain, Timothy Folger, who told him this might very well be true because the Rhode Island captains were well acquainted with the Gulf Stream and avoided it on the westward crossing, whereas the English captains were not. Folger and other Nantucket whalers were personally familiar with the Stream because, he explained,

in our pursuit of whales, which keep to the sides of it but are not met within it, we run along the side and frequently cross it to change our side, and in crossing it have sometimes met and spoke with those packets who were in the middle of it and stemming it. We have informed them that they were stemming a current that was against them to the value of three miles an hour and advised them to cross it, but they were too wise to be counselled by simple American fishermen.

*

Franklin, thinking âit was a pity no notice was taken of this current upon the charts,' asked Folger to mark it out for him. The course of the Gulf Stream was then engraved on an old chart of the Atlantic and sent by Franklin to Falmouth, England, for the captains of the packets, âwho slighted it, however.' It was later printed in France and after the Revolution was published in the

Transactions of the American Philosophical Society.

The thriftiness of the Philosophical Society editors led them to combine in one plate Franklin's chart and a wholly separate figure intended to illustrate a paper by John Gilpin on the âAnnual Migrations of the Herring.' Some later historians have erroneously assumed a connection between Franklin's conception of the Gulf Stream and the insert in the upper left corner

Were it not for the deflecting barrier of the Panamanian isthmus, the North Equatorial Current would cross into the Pacific, as indeed it must have done through the many geologic ages when the continents of North and South America were separated. After the Panama ridge was formed in the late Cretaceous period, the current was doubled back to the northeast to re-enter the Atlantic as the Gulf Stream. From the Yucatan Channel eastward through the Florida Straits the Stream attains impressive proportions. If thought of in the time-honored conception of a âriver' in the sea, its width from bank to bank is 95 miles. It is a mile deep from surface to river bed. It flows with a velocity of nearly three knots and its volume is that of several hundred Mississippis.

Even in these days of Diesel power, the coastwise shipping off southern Florida shows a wholesome respect for the Gulf Stream. Almost any day, if you are out in a small boat below Miami, you can see the big freighters and tankers moving south in a course that seems surprisingly close to the Keys. Landward is the almost unbroken wall of submerged reefs where the big niggerhead corals send their solid bulks up to within a fathom or two of the surface. To seaward is the Gulf Stream, and while the big boats could fight their way south against it, they would consume much time and fuel in doing so. Therefore they pick their way with care between the reefs and the Stream.

The energy of the Stream off southern Florida probably results from the fact that here it is actually flowing downhill. Strong easterly winds pile up so much surface water in the narrow Yucatan Channel and in the Gulf of Mexico that the sea level there is higher than in the open Atlantic. At Cedar Keys, on the Gulf coast of Florida, the level of the sea is 19 centimeters (about 7½ inches) higher than at St. Augustine. There is further unevenness of level within the current itself. The lighter water is deflected by the earth's rotation toward the right side of the current, so that within the Gulf Stream the sea surface actually slopes upward toward the right. Along the coast of Cuba, the ocean is about 18 inches higher than along the mainland, thus upsetting completely our notions that âsea level' is literal expression.

Northward, the Stream follows the contours of the continental slope to the offing of Cape Hatteras, whence it turns more to seaward, deserting the sunken edge of the land. But it has left its impress on the continent. The four beautifully sculptured capes of the southern Atlantic coastâCanaveral, Fear, Lookout, Hatterasâapparently have been molded by powerful eddies set up by the passage of the Stream. Each is a cusp projecting seaward; between each pair of capes the beach runs in a long curving arcâthe expression of the rhythmically swirling waters of the Gulf Stream eddies.

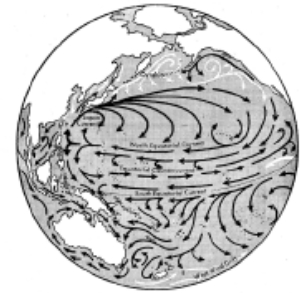

Course of the great, wind-driven current systems of the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. Cold currents appear in white; warm or intermediate ones in black.

Beyond Hatteras, the Stream leaves the shelf, turning north-eastward, as a narrow, meandering current, always sharply separated from the water on either side. Off the âtail' of the Grand Banks the line is most sharply drawn between the cold, bottle-green arctic water of the Labrador Current and the warm indigo blue of the Stream. In winter the temperature change across the current boundary is so abrupt that as a ship crosses into the Gulf Stream her bow may be momentarily in water 20° warmer than that at her stern, as though the âcold wall' were a solid barrier separating the two water masses. One of the densest fog banks in the world lies in this region over the cold water of the Labrador Currentâa thick, blanketing whiteness that is the atmospheric response to the Gulf Stream's invasion of the cold northern seas.

Where the Stream feels the rise of the ocean floor known as the âtail' of the Grand Banks, it bends eastward and begins to spread out into many complexly curving tongues. Probably the force of the arctic water, the water that has come down from Baffin Bay and Greenland, freighting its icebergs, helps push the Stream to the eastâthat, and the deflecting force of the earth's rotation, always turning the currents to the right. The Labrador Current itself (being a southward-moving current) is turned in toward the mainland. The next time you wonder why the water is so cold at certain coastal resorts of the eastern United States, remember that the water of the Labrador Current is between you and the Gulf Stream.

Passing across the Atlantic, the Stream becomes less a current than a drift of water, fanning out in three main directions: southward into the Sargasso; northward into the Norwegian Sea, where it forms eddies and deep vortices; eastward to warm the coast of Europe (some of it even to pass into the Mediterranean) and thence as the Canary Current to rejoin the Equatorial Current and close the circuit.

*

The Atlantic currents of the Southern Hemisphere are practically a mirror image of those of the Northern. The great spiral moves counterclockwiseâwest, south, east, north. Here the dominant current is in the eastern instead of the western part of the ocean. It is the Benguela Current, a river of cold water moving northward along the west coast of Africa. The South Equatorial Current, in mid-ocean a powerful stream (the

Challenger

scientists said it poured past St. Paul's Rocks like a millrace) loses a substantial part of its waters to the North Atlantic off the coast of South Americaâabout 6 million cubic meters a second. The remainder becomes the Brazil Current, which circles south and then turns east as the South Atlantic or Antarctic Current. The whole is a system of shallow water movements, involving throughout much of its course not more than the upper hundred fathoms.

The North Equatorial Current of the Pacific is the longest westerly running current on earth, with nothing to deflect it in its 9000-mile course from Panama to the Philippines. There, meeting the barrier of the islands, most of it swings northward as the Japan CurrentâAsia's counterpart of the Gulf Stream. A small part persists on its westward course, feeling its way amid the labyrinth of Asiatic islands; part turns upon itself and streams back along the equator as the Equatorial Countercurrent. The Japan Currentâcalled Kuroshio or Black Current because of the deep, indigo blue of its watersârolls northward along the continental shelf off eastern Asia, until it is driven away from the continent by a mass of icy waterâthe Oyashioâthat pours out of the Sea of Okhotsk and Bering Sea. The Japan Current and Oyashio meet in a region of fog and tempestuous winds, as, in the North Atlantic, the meeting of the Gulf Stream and the Labrador Current is marked with fog. Drifting toward America, the Japan Current forms the northern wall of the great North Pacific eddy. Its warm waters become chilled with infusions of cold polar water from Oyashio, the Aleutians, and Alaska. When it reaches the mainland of America it is a cool current, moving southward along the coast of California. There it is further cooled by updrafts of deep water and has much to do with the temperate summer climate of the American west coast. Off Lower California it rejoins the North Equatorial Current.

What with all the immensity of space in the South Pacific, we should expect to find here the most powerfully impressive of all ocean currents, but this does not seem to be true. The South Equatorial Current has its course so frequently interrupted by islands, which are forever deflecting streams of its water into the central basin, that by the time it approaches Asia it is, during most seasons, a comparatively feeble current, lost in a confused and ill-defined pattern around the East Indies and Australia.

*

The West Wind Drift or Antarctic Currentâthe poleward arc of the spiralâis born of the strongest winds in the world, roaring across stretches of ocean almost unbroken by land. The details of this, as of most of the currents of the South Pacific, are but imperfectly known. Only one has been thoroughly studiedâthe Humboldtâand this has so direct an effect on human affairs that it overshadows all others.

The Humboldt Current, sometimes called the Peru, flows northward along the west coast of South America, carrying waters almost as cold as the Antarctic from which it comes. But its chill is actually that of the deep ocean, for the current is reinforced by almost continuous upwelling from lower oceanic layers. It is because of the Humboldt that penguins live almost under the equator, on the Galapagos Islands. In these cold waters, rich in minerals, there is an abundance of sea life perhaps unparalleled anywhere else in the world. The direct harvesters of this sea life are not men, but millions of sea birds. From the sun-baked accumulations of guano that whiten the coastal cliffs and islands, the South Americans obtain, at second hand, the wealth of the Humboldt Current.