The Scourge of God

Read The Scourge of God Online

Authors: William Dietrich

To my mother, and in memory of my father.

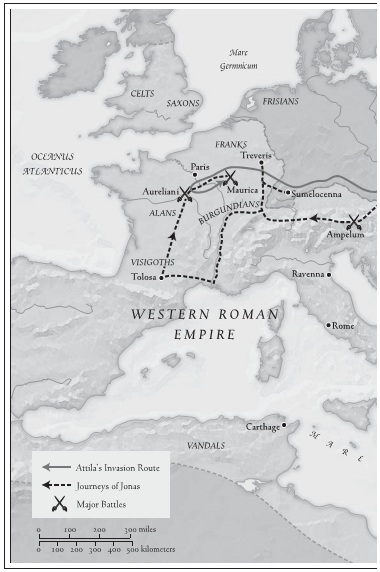

They gave me a children’s book recounting the Battle of Chalons and sparked a lifelong curiosity.

Contents

Part One The Embassy to Attila

VIII The Hospitality of the Huns

Part Three The Battle of Nations

Other Books by William Dietrich

ROMANS AND FRIENDS

Jonas Alabanda: A young Roman envoy and scribe

Ilana: A captive Roman maiden

Zerco: A dwarfjester who befriends Jonas

Julia: Zerco’s wife

Aetius: A Roman general

Valentinian III: Emperor of the Western Roman Empire

Galla Placidia: Valentinian’s mother

Honoria: Valentinian’s sister

Hyacinth: Honoria’s eunuch

Theodosius II: Emperor of the Eastern Roman Empire

Chrysaphius: His eunuch minister

Maximinus: Ambassador to Attila

Bigilas: A translator and conspirator

Rusticius: A translator

Anianus: Bishop and (when it suits him) hermit

THE HUNS

Attila: King of the Huns

Skilla: A Hun warrior who loves Ilana

Edeco: Uncle of Skilla and warlord of Attila

Suecca: Edeco’s wife

Eudoxius: A Greek doctor who is an envoy of Attila

Hereka: Attila’s first wife

Ellac, Danziq, and Ernak: Attila’s sons

Onegesh: A Roman-born lieutenant of Attila

THE GERMANS

Guernna: A captive like Ilana

Theodoric: King of the Visigoths

Berta: Theodoric’s daughter

Gaiseric: King of the Vandals

Sangibanus: King of the Alans

Anthus: King of the Franks

|

T

hree hundred and seventy-six years after the birth of Our Savior, the world was still one. Our Roman Empire endured as it had endured for a thousand years, extending from the cold moors of Britannia to the blistering sands of Arabia, and from the headwaters of the Euphrates River to the Atlantic surf of North Africa. Rome’s boundaries had been tested countless times by Celt and German, Persian and Scythian. Yet with blood and iron, guile and gold, all invaders had been turned back. It had always been so, and in 376 it seemed it must always be so.

How I wish I had lived in such security!

But I, Jonas Alabanda—historian, diplomat, and reluctant soldier—can only imagine the old Empire’s venerable stability the way a sailor’s audience imagines a faraway and misty shore. My fate has been to exist in harder times, meeting the great and living more desperately because of it. This book is my story and those I had the fortune and misfortune to observe, but its roots are older. In that year 376, more than half a century before I was born, came the first rumor of the storm that forever changed everything.

In that year, historians recount, came the first rumor of the Huns.

Understand that I am by origin an Easterner, fluent in Greek, conversant with philosophy, and used to the dazzling sun. My home is Constantinople, the city that Constantine the Great founded on the Bosporus in order to ease the administration of our Empire by creating a second capital. At that junction of Europe and Asia, where the Black Sea and Mediterranean join, rose Nova Roma, the strategic site of ancient Byzantium. This division gave Rome two emperors, two Senates, and two cultures: the Latin West and Greek East. But Rome’s armies still marched in support of both halves and the Empire’s laws were coordinated and unified. The Mediterranean remained a Roman lake; and Roman architecture, coinage, forums, fortresses, and churches could be found from the Nile to the Thames. Christianity eclipsed all other religions, and Latin all other tongues. The world had never before known such a long period of relative peace, stability, and unity.

It never would again.

The Danube is Europe’s greatest river, rising at the foot of the Alps and running eastward nearly eighteen hundred miles before emptying into the Black Sea. In 376 its length marked much of the Empire’s northern border. That summer, Roman garrisons at posts along the river began to hear reports of war, upheaval, and migration among the barbarian nations. Some new terror unlike any the world had ever seen was putting entire peoples to flight, stories went, each tribe colliding with the one to its west. Fugitives described an ugly, swarthy, stinking people who wore animal skins until they rotted off their backs, who were immune to hunger and thirst but drank the blood of their horses, and who ate raw meat tenderized beneath their saddles. These new invaders arrived as silently as the wind, killed with powerful bows from an unprecedented distance, massacred with swords any who still resisted, and then galloped away before cohesive retaliation could form. They disdained proper shelter, burning all they encountered and living much of the time under the sky. Their cities consisted of felt tents, their highways the trackless steppes. They rolled across the grasslands in sturdy wagons heaped with booty and trailed by slaves, and their tongue was harsh and guttural.

They called themselves the Huns.

Surely this news was exaggerated, our sentries assured each other. Surely fact had become confused by rumor. Rome had long experience with barbarians and knew that, while individually courageous, such warriors were poor tacticians and worse strategists. Fearsome as enemies, they were valuable as allies. Had not the terrible Germans become, over the centuries, a bulwark of the Roman army in the West? Had not the wild Celts been civilized? Couriers reported to Rome and Constantinople that something unusual seemed to be happening in the lands beyond the Danube, but its danger was still unclear.

Then rumor turned into a flood of refugees.

A quarter million people from a Germanic nation known as the Goths appeared on the north bank of the river, seeking asylum from the marauding Huns. With no way to stop such a migration short of war, my ancestors reluctantly gave the Goths permission to cross to the southern shore. Perhaps these newcomers, like so many tribes before them, could be safely settled and become “federates” of the Empire like the unruly but calculating Franks: an allied bulwark against the mysterious steppe people.

It was an unrealistic hope, born of expediency. The Goths were proud and unconquered. We civilized peoples seemed pampered, vacillating, and weak. Romans and Goths soon quarreled. Refugees were sold dog meat and stole cattle in return. They became plunderers and then outright invaders. So on August 9,

a.d.

378, the Eastern Roman Emperor Valens fought the Goths outside the city of Hadri-anopolis, just one hundred and fifty miles from Constantinople itself. The numbers were evenly matched and we Romans were confident of victory. But our cavalry fled; our infantry panicked; and, surrounded by Gothic horsemen, our soldiers were packed so tightly together that they could not raise arms and shields to fight effectively. Valens and his army were destroyed in the worst Roman military disaster since Hannibal had annihilated the Romans at Cannae, almost six centuries before.

An ominous precedent had been set: The Roman army could be beaten by barbarians. In fact, the Romans could be beaten by barbarians who were fleeing even

more

fearsome barbarians.

Worse was soon to come.

The Goths began a pillaging migration across the Empire that would not stop for decades. Meanwhile, the Huns ravaged the Danube River valley; and, far to the east, they pillaged Armenia, Cappadocia, and Syria. Whole barbarian nations were uprooted, and some of these migrating tribes stacked up on the Rhine. When that river froze solid on the last day of 406, Vandals, Alans, Suevi, and Burgundians swarmed across to fall on Gaul. The barbarians swept south, burning, killing, looting, and raping in an orgy of violence that produced the horrid and fascinating tales my generation was weaned on. A Roman woman was discovered to have cooked and eaten her four children, one by one, explaining to authorities that she hoped each sacrifice would save the others. Her neighbors stoned her to death.

The invaders crossed the Pyrenees to Hispania, and then Gibraltar to Africa. Saint Augustine died while his North African home city of Hippo was under siege. Britannia was cut off, lost to the Empire. The Goths, still seeking a homeland, swept into Italy and in 410 shocked the world by sacking Rome itself. Although they withdrew after just three days of pillage, the sacred city’s sense of inviolability had been shattered.