The Science of Language (31 page)

Read The Science of Language Online

Authors: Noam Chomsky

Appendix VII: Hierarchy, structure, domination, c-command, etc.

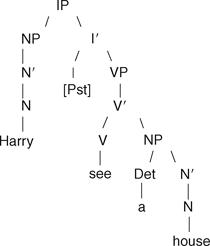

The sentences of natural languages all display hierarchical structure. Structure is often represented in a tree; a tree for a simple sentence such as

Harry saw a house

drawn in a way that reflects a fairly recent version of generative syntax might

look like this:

Harry saw a house

drawn in a way that reflects a fairly recent version of generative syntax might

look like this:

The labels on the diagram are explained below.

I briefly address two questions: (i) where do linguistic hierarchical structures ‘come from,’ and (ii) what is their significance for understanding the way that language ‘works’?

On the first question, it is important to recognize that it is difficult to avoid

hierarchy. The successor function for generating the natural numbers introduces it, and in fact any finite state grammar introduces hierarchy: each additional element added in generating a string of words or other elements yields a larger set of which the prior-generated set is a subset. If one adds the operation of associativity, one can make the hierarchy disappear and end up with a string, but that requires an additional operation – and justification for introducing it. I do not mention a finite state grammar because it introduces the right hierarchy for natural languages. Chomsky demonstrated long ago

that it did not (

1957

; see also Chomsky & Miller

1963

). The issue is not how some kind of hierarchy is introduced, but rather how the ‘right’ kind is – the kind of hierarchy found in natural languages. The ‘right’ kinds of grammar yield this.

hierarchy. The successor function for generating the natural numbers introduces it, and in fact any finite state grammar introduces hierarchy: each additional element added in generating a string of words or other elements yields a larger set of which the prior-generated set is a subset. If one adds the operation of associativity, one can make the hierarchy disappear and end up with a string, but that requires an additional operation – and justification for introducing it. I do not mention a finite state grammar because it introduces the right hierarchy for natural languages. Chomsky demonstrated long ago

that it did not (

1957

; see also Chomsky & Miller

1963

). The issue is not how some kind of hierarchy is introduced, but rather how the ‘right’ kind is – the kind of hierarchy found in natural languages. The ‘right’ kinds of grammar yield this.

Answers to this question have changed over the last sixty years or so, demonstrating progress in developing the study of language into a natural science. To illustrate, consider two stages on the way to the

minimalist program approach to explaining structure, the earliest (1950s on) ‘

phrase structure grammar’ one and the later (beginning about 1970) X-bar theory approach. Historically speaking, these are not distinct stages; it is better to think in terms of evolving views. However, for purposes of explication, I compress and idealize. During the first stage, linguistic structure in the derivation of a sentence was attributed primarily to phrase structure rewrite rules that included some like this:

minimalist program approach to explaining structure, the earliest (1950s on) ‘

phrase structure grammar’ one and the later (beginning about 1970) X-bar theory approach. Historically speaking, these are not distinct stages; it is better to think in terms of evolving views. However, for purposes of explication, I compress and idealize. During the first stage, linguistic structure in the derivation of a sentence was attributed primarily to phrase structure rewrite rules that included some like this:

S → NP + VP (‘Sentences’ [more carefully, abstract descriptions of structures and LIs] consist of Noun Phrases followed by Verb Phrases.)

VP → V + NP

V → V + AUX

V → {leave, choose, want, drink, fall. . .}

. . . and so on, in very considerable detail, tailored to specific natural languages. These rules, it was thought, and a few “obligatory” transformations, yielded

Deep Structures. The Deep Structures then could be subject to “optional” transformations that would (for instance) move elements around and perhaps add or subtract some in order to (for instance) change a declarative structure into a passive one. Basically, though, transformations depended on the basic structure established by the phrase structure grammar. So to the question, where does structure come from, the answer is: the phrase structure component of a grammar, modified where appropriate and needed by a transformational component. Notice that this kind of answer is not very different from answering the question of where the structures of molecules come from by saying “this is the way atoms combine” with no further explanation of why atoms do so in the ways they do. In effect, phrase structure grammars are descriptive, not explanatory in any illuminating sense. Segmenting linguistic derivations into a phrase structure component and a transformational one simplifies things a bit, and phrase structure grammars greatly reduce the number of rules that a child is conceived of as required to learn to acquire a language. However, that is a long way from offering a workable answer to how the child manages to acquire a language in the way the poverty of

stimulus observations indicate. So phrase structure grammars do not do much more than begin to speak to the issue of acquisition: because structure differs from language to language (a prime example is the verbal auxiliary system), rewrite rules are far from

universally applicable, making it difficult to understand how specific grammars could be acquired under poverty of stimulus conditions. They also leave wide open the question of how language came to have the hierarchical structure it does. They offer no way to trace language's structure to biology and/or other sciences, and do not speak at all to the question of why only humans seem to have the structure available to them – structure that is, furthermore, usable in cognition in general, including thought and speculation. Indeed, because so many variants are required for different languages, they make it even more difficult to imagine how they could have a biological basis.

Deep Structures. The Deep Structures then could be subject to “optional” transformations that would (for instance) move elements around and perhaps add or subtract some in order to (for instance) change a declarative structure into a passive one. Basically, though, transformations depended on the basic structure established by the phrase structure grammar. So to the question, where does structure come from, the answer is: the phrase structure component of a grammar, modified where appropriate and needed by a transformational component. Notice that this kind of answer is not very different from answering the question of where the structures of molecules come from by saying “this is the way atoms combine” with no further explanation of why atoms do so in the ways they do. In effect, phrase structure grammars are descriptive, not explanatory in any illuminating sense. Segmenting linguistic derivations into a phrase structure component and a transformational one simplifies things a bit, and phrase structure grammars greatly reduce the number of rules that a child is conceived of as required to learn to acquire a language. However, that is a long way from offering a workable answer to how the child manages to acquire a language in the way the poverty of

stimulus observations indicate. So phrase structure grammars do not do much more than begin to speak to the issue of acquisition: because structure differs from language to language (a prime example is the verbal auxiliary system), rewrite rules are far from

universally applicable, making it difficult to understand how specific grammars could be acquired under poverty of stimulus conditions. They also leave wide open the question of how language came to have the hierarchical structure it does. They offer no way to trace language's structure to biology and/or other sciences, and do not speak at all to the question of why only humans seem to have the structure available to them – structure that is, furthermore, usable in cognition in general, including thought and speculation. Indeed, because so many variants are required for different languages, they make it even more difficult to imagine how they could have a biological basis.

The second, X-bar approach made some progress. There are a couple of ways of looking at X-bar theory. One is this: instead of appearing as in phrase structure grammars to try to build structure top-down, move instead from lexical items up. Assume that lexical items come already placed in a small set of possible categories, where each item in each

category has a set of features that in effect say what the relevant lexical item can do in a derivation/computation. Thus, as a lexical item ‘projects’ up through the structure, it carries its features with it, and these determine how they can combine, where, and how they will be read. The categories are N (for noun), V (verb), A (adjective/adverb) and – with some dispute concerning its fundamental character – P (post/preposition). The projected structures are reasonably close to being common to all languages. The structures that are built consist of three ‘bar levels’ – so-called because the original way of representing the level of the structure took an N, say, and represented the first or “zero” level of structure as the lexical item itself (N), the next level as an ‘N’ with a single bar written on top, and the third an ‘N’ with two bars. A more convenient notation looks like this: N

0

, N

1

, N

2

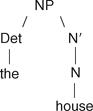

or this: N, N′, N″. The number of primes corresponds to the number of ‘levels” to be found in a hierarchical structure that looks like this, for a noun:

category has a set of features that in effect say what the relevant lexical item can do in a derivation/computation. Thus, as a lexical item ‘projects’ up through the structure, it carries its features with it, and these determine how they can combine, where, and how they will be read. The categories are N (for noun), V (verb), A (adjective/adverb) and – with some dispute concerning its fundamental character – P (post/preposition). The projected structures are reasonably close to being common to all languages. The structures that are built consist of three ‘bar levels’ – so-called because the original way of representing the level of the structure took an N, say, and represented the first or “zero” level of structure as the lexical item itself (N), the next level as an ‘N’ with a single bar written on top, and the third an ‘N’ with two bars. A more convenient notation looks like this: N

0

, N

1

, N

2

or this: N, N′, N″. The number of primes corresponds to the number of ‘levels” to be found in a hierarchical structure that looks like this, for a noun:

Phrases of other types can stem from the N′ position; when they are found there, they are “adjuncts.” A hierarchical drawing for

the green house

with the adjective (A)

green

as an adjunct would place a branch of the tree stemming from the diagram's N′ down to the left (for English) to an AP, which would then go to an A′ and in turn to an A, and finally to

green

.

‘Det’ is short for “determiner”; determiners for noun phrases include

the

and

a

(in English). The position occupied by ‘Det’ in the diagram is the “specifier” position. X′s have specifiers; a specifier for a sentence (now an “inflectional phrase” to capture the idea that “inflections” such as tense need to be added to verbs to get sentences as we normally think of them) would normally be an NP.

the green house

with the adjective (A)

green

as an adjunct would place a branch of the tree stemming from the diagram's N′ down to the left (for English) to an AP, which would then go to an A′ and in turn to an A, and finally to

green

.

‘Det’ is short for “determiner”; determiners for noun phrases include

the

and

a

(in English). The position occupied by ‘Det’ in the diagram is the “specifier” position. X′s have specifiers; a specifier for a sentence (now an “inflectional phrase” to capture the idea that “inflections” such as tense need to be added to verbs to get sentences as we normally think of them) would normally be an NP.

Another way to look at X-bar structure is to conceive of it as required to conform to a set of three schemata. The schemata are:

1.Specifier schema: XP → (YP) – X′

2.Adjunct schema: X′ → (YP) – X′

3.Complement schema: X′ → X – (YP)

X = any of N, V, A, P

P = phrase

(. . .) = optional

− = order either way

Details concerning X-bar theory and structure are available in many places; my aim is to speak to what its introduction accomplished. X-bar theory, however one conceives of it,

simplifies the structure that phrase structure grammar once was used to describe a great deal. The schemata or projection principles capture all the possible phrasal structures of all languages, thereby making a case as linguistic universals; and joined to the early stages of the

principles and parameters framework as it was after 1980, X-bar could accommodate at least the headedness parameter. To the extent that it reduced multiple rule systems into a relatively simple set of schemata or projection principles, it aided – at least to a degree – the task of speaking to the

acquisition issue and the matter of accommodating the theory of language to biology (the genome). It still left a lot unexplained: why this form, why three ‘bar levels,’ and where did this structure come from? However, it did speak to the matter of simplicity, and also to another important issue that Chomsky emphasizes in comments on an earlier draft of this appendix. In phrase structure grammar, even more was left unexplained. Phrase structure grammar simply stipulates abstract structures as NP, VP, S and stipulates too the rules in which they figure. Because of this, it offered no principled reason for the rule V → V NP rather than V → CP N. X-bar theory eliminated the wrong options and the stipulated formal technology in a more principled way than did phrase structure grammar. Again, that represents

progress.

simplifies the structure that phrase structure grammar once was used to describe a great deal. The schemata or projection principles capture all the possible phrasal structures of all languages, thereby making a case as linguistic universals; and joined to the early stages of the

principles and parameters framework as it was after 1980, X-bar could accommodate at least the headedness parameter. To the extent that it reduced multiple rule systems into a relatively simple set of schemata or projection principles, it aided – at least to a degree – the task of speaking to the

acquisition issue and the matter of accommodating the theory of language to biology (the genome). It still left a lot unexplained: why this form, why three ‘bar levels,’ and where did this structure come from? However, it did speak to the matter of simplicity, and also to another important issue that Chomsky emphasizes in comments on an earlier draft of this appendix. In phrase structure grammar, even more was left unexplained. Phrase structure grammar simply stipulates abstract structures as NP, VP, S and stipulates too the rules in which they figure. Because of this, it offered no principled reason for the rule V → V NP rather than V → CP N. X-bar theory eliminated the wrong options and the stipulated formal technology in a more principled way than did phrase structure grammar. Again, that represents

progress.

Minimalism is a program for advanced research in linguistics. It is not a theory. It is a program that aims to answer questions such as the ones left unanswered by earlier attempts at dealing with linguistic structure. It

became possible because linguists around the beginning of the 1990s could – because of a lot of evidence in its favor – rely on the

principles and parameters framework, and particularly on parameters. They could afford, then, to set aside the explanatory issue that dominated research until that time, that of

speaking to Plato's Problem. They could – as the discussion of the main text emphasizes in several ways – go “beyond explanation” (as the title of one of Chomsky's papers reads), meaning by that not by any means that they could consider the task of explanation complete, but that they could speak to other, deeper explanatory issues, such as those raised by evolution and the fact that language is unique to human beings, and by ‘Where does structure comes from?’, ‘Why this structure?’, and ‘What does the structure accomplish?’ For obvious reasons, Merge – its nature, its introduction to the

human species, and what it can do – and third factor

considerations came as a result to be placed at the forefront of research. Since the main text and other appendices speak to what this new focus provided (the structure introduced by Merge and the variants in structure offered, possibly, by third factor considerations alone), I do not repeat it here. I just emphasize that even coming to the point where minimalism could come to be taken seriously as a scientific program of research represents great (but definitely not finished) progress on the way to making linguistics a naturalistic science. Only once it is possible to initiate it can one begin to see how the theory of language and of linguistic structure could be accommodated to other

sciences.

became possible because linguists around the beginning of the 1990s could – because of a lot of evidence in its favor – rely on the

principles and parameters framework, and particularly on parameters. They could afford, then, to set aside the explanatory issue that dominated research until that time, that of

speaking to Plato's Problem. They could – as the discussion of the main text emphasizes in several ways – go “beyond explanation” (as the title of one of Chomsky's papers reads), meaning by that not by any means that they could consider the task of explanation complete, but that they could speak to other, deeper explanatory issues, such as those raised by evolution and the fact that language is unique to human beings, and by ‘Where does structure comes from?’, ‘Why this structure?’, and ‘What does the structure accomplish?’ For obvious reasons, Merge – its nature, its introduction to the

human species, and what it can do – and third factor

considerations came as a result to be placed at the forefront of research. Since the main text and other appendices speak to what this new focus provided (the structure introduced by Merge and the variants in structure offered, possibly, by third factor considerations alone), I do not repeat it here. I just emphasize that even coming to the point where minimalism could come to be taken seriously as a scientific program of research represents great (but definitely not finished) progress on the way to making linguistics a naturalistic science. Only once it is possible to initiate it can one begin to see how the theory of language and of linguistic structure could be accommodated to other

sciences.

The second issue concerning structure is what it is for – what linguistic structure does. In what follows, keep in mind again that any grammar introduces structure and hierarchy; the crucial issue is what is the right structure and grammar (and getting principled answers to this question, ultimately by appeal to biology). In the same vein, one should keep in mind that what is commonly called “weak generative capacity” (the capacity of a grammar to yield a set of unstructured strings) is a

less

primitive operation than strong generation (yielding strings with structures – in the case of language, stated in terms of structural descriptions or structural specifications).

Weak generative capacity involves a second operation – perhaps associativity, as indicated above.

less

primitive operation than strong generation (yielding strings with structures – in the case of language, stated in terms of structural descriptions or structural specifications).

Weak generative capacity involves a second operation – perhaps associativity, as indicated above.

As for the (connected) issue of what structures

do

: there have been several answers, but also a degree of agreement. Structures constitute phrases, and phrases are domains that play central roles in determining what can move where, and what the various elements of a phrase ‘do’ – what kind of theta role a noun phrase might have, for example. I illustrate in a very small way by looking at the notion of c-command – how it is defined over hierarchical structures and some of the principles in which it is involved. For ‘c,’ read ‘constituent,’ hence “constituent command.”

do

: there have been several answers, but also a degree of agreement. Structures constitute phrases, and phrases are domains that play central roles in determining what can move where, and what the various elements of a phrase ‘do’ – what kind of theta role a noun phrase might have, for example. I illustrate in a very small way by looking at the notion of c-command – how it is defined over hierarchical structures and some of the principles in which it is involved. For ‘c,’ read ‘constituent,’ hence “constituent command.”

Other books

Area 51: The Sphinx-4 by Robert Doherty

KnightForce Deuces by Sydney Addae

Jaded Moon (Ransomed Jewels Book 2) by Laura Landon

Trace's Temptation (RARE Series, #3) by Dawn Sullivan

Devil and the Deep (The Ceruleans: Book 4) by Tayte, Megan

Georgia Peaches and Other Forbidden Fruit by Jaye Robin Brown

Swordsman of Lost Terra by Poul Anderson

Taking the Knife by Linsey, Tam

Death at the Devil's Tavern by Deryn Lake