The Savage Tales of Solomon Kane (45 page)

Read The Savage Tales of Solomon Kane Online

Authors: Robert E. Howard,Gary Gianni

Then it was that the Bogondi, seeing they could not hope to win through the hills, sought to fight their way out again the way they had come. But a great horde of cannibals met them in the grasslands and in a great battle that lasted nearly all day, hurled them back, broken and defeated. And Goru said while the battle raged, the skies were thronged with hideous shapes, circling above and laughing their fearful mirth to see men die wholesale.

So the survivors of those two battles, licking their wounds, bowed to the inevitable with the fatalistic philosophy of the black man. Some fifteen hundred men, women and children remained, and they built their huts, tilled the soil and lived stolidly in the shadow of the nightmare.

In those days there were many of the bird-people, and they might have wiped out the Bogondi utterly, had they wished. No one warrior could cope with an akaana, for he was stronger than a human, he struck as a hawk strikes, and if he missed, his wings carried him out of reach of a counter-blow. Here Kane interrupted to ask why the blacks did not make war on the demons with arrows. But Goru answered that it took a quick and accurate archer to strike an akaana in midair at all and so tough were their hides that unless the arrow struck squarely it would not penetrate. Kane knew that the blacks were very indifferent bowmen and that they pointed their shafts with chipped stone, bone or hammered iron almost as soft as copper; he thought of Poitiers and Agincourt and wished grimly for a file of stout English archers – or a rank of musketeers.

But Goru said the akaanas did not seem to wish to destroy the Bogondi utterly. Their chief food consisted of the little pigs which then swarmed the plateau, and young goats. Sometimes they went out on the savannas for antelope, but they distrusted the open country and feared the lions. Nor did they haunt the jungles beyond, for the trees grew too close for the spread of their wings. They kept to the hills and the plateau – and what lay beyond those hills none in Bogonda knew.

The akaanas allowed the black folk to inhabit the plateau much as men allow wild animals to thrive, or stock lakes with fish – for their own pleasure. The bat-people, said Goru, had a strange and grisly sense of humor which was tickled by the sufferings of a howling human. Those grim hills had echoed to cries that turned men's hearts to ice.

But for many years, Goru said, once the Bogondi learned not to resist their masters, the akaanas were content to snatch up a baby from time to time, or devour a young girl strayed from the village or a youth whom night caught outside the walls. The bat-folk distrusted the village; they circled high above it but did not venture within. There the Bogondi were safe until late years.

Goru said that the akaanas were fast dying out; once there had been hope that the remnants of his race would outlast them – in which event, he said fatalistically, the cannibals would undoubtedly come up from the jungle and put the survivors in the cooking-pots. Now he doubted if there were more than a hundred and fifty akaanas altogether. Kane asked him why did not the warriors then sally forth on a great hunt and destroy the devils utterly, and Goru smiled a bitter smile and repeated his remarks about the prowess of the bat-people in battle. Moreover, said he, the whole tribe of Bogonda numbered only about four hundred souls now, and the bat-people were their only protection against the cannibals to the west.

Goru said the tribe had thinned more in the past thirty years than in all the years previous. As the numbers of the akaanas dwindled, their hellish savagery increased. They seized more and more of the Bogondi to torture and devour in their grim black caves high up in the hills, and Goru spoke of sudden raids on hunting-parties and toilers in the plantain fields and of the nights made ghastly by horrible screams and gibberings from the dark hills, and blood-freezing laughter that was half human; of dismembered limbs and gory grinning heads flung from the skies to fall in the shuddering village, and of grisly feasts among the stars.

Then came drouth, Goru said, and a great famine. Many of the springs dried up and the crops of rice and yams and plantains failed. The gnus, deer and buffaloes which had formed the main part of Bogonda's meat diet withdrew to the jungle in quest of water, and the lions, their hunger overcoming their fear of man, ranged into the uplands. Many of the tribe died and the rest were driven by hunger to eat the pigs which were the natural prey of the bat-people. This angered the akaanas and thinned the pigs. Famine, Bogondi and the lions destroyed all the goats and half the pigs.

At last the famine was past, but the damage was done. Of all the great droves which once swarmed the plateau, only a remnant was left and these were wary and hard to catch. The Bogondi had eaten the pigs, so the akaanas ate the Bogondi. Life became a hell for the black people, and the lower village, numbering now only some hundred and fifty souls, rose in revolt. Driven to frenzy by repeated outrages, they turned on their masters. An akaana lighting in the very streets to steal a child was set on and shot to death with arrows. And the people of Lower Bogonda drew into their huts and waited for their doom.

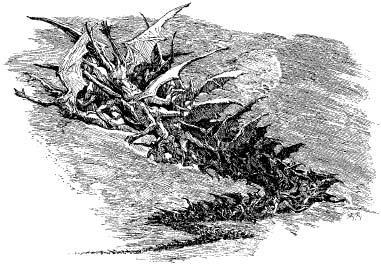

And in the night, said Goru, it came. The akaanas had overcome their distrust of the huts. The full flock of them swarmed down from the hills, and Upper Bogonda awoke to hear the fearful cataclysm of screams and blasphemies that marked the end of the other village. All night Goru's people had lain sweating in terror, not daring to move, harkening to the howling and gibbering that rent the night; at last these sounds ceased, Goru said, wiping the cold sweat from his brow, but sounds of grisly and obscene feasting still haunted the night with demon's mockery.

In the early dawn Goru's people saw the hell-flock winging back to their hills, like demons flying back to hell through the dawn, and they flew slowly and heavily, like gorged vultures. Later the people dared to steal down to the accursed village, and what they found there sent them shrieking away; and to that day, Goru said, no man passed within three bowshots of that silent horror. And Kane nodded in understanding, his cold eyes more somber than ever.

For many days after that, Goru said, the people waited in quaking fear, and finally in desperation of fear, which breeds unspeakable cruelty, the tribe cast lots and the loser was bound to a stake between the two villages, in hopes the akaanas would recognize this as a token of submission so that the people of Bogonda might escape the fate of their kinsmen. This custom, said Goru, had been borrowed from the cannibals who in old times worshipped the akaanas and offered a human sacrifice at each moon. But chance had shown them that the akaana could be killed, so they ceased to worship him – at least that was Goru's deduction, and he explained at much length that no mortal thing is worthy of real adoration, however evil or powerful it may be.

His own ancestors had made occasional sacrifices to placate the winged devils, but until lately it had not been a regular custom. Now it was necessary; the akaanas expected it, and each moon they chose from their waning numbers a strong young man or a girl whom they bound to the stake. Kane watched Goru's face closely as he spoke of his sorrow for this unspeakable necessity, and the Englishman realized the priest was sincere. Kane shuddered at the thought of a tribe of human beings thus passing slowly but surely into the maws of a race of monsters.

Kane spoke of the wretch he had seen, and Goru nodded, pain in his soft eyes. For a day and a night he had been hanging there, while the akaanas glutted their vile torture-lust on his quivering, agonized flesh. Thus far the sacrifices had kept doom from the village. The remaining pigs furnished sustenance for the dwindling akaanas, together with an occasional baby snatched up, and they were content to have their nameless sport with the single victim each moon.

A thought came to Kane.

“The cannibals never come up into the plateau?”

Goru shook his head; safe in their jungle, they never raided past the savannas.

“But they hunted me to the very foot of the hills.”

Again Goru shook his head. There was only one cannibal; they had found his footprints. Evidently a single warrior, bolder than the rest, had allowed his passion for the chase to overcome his fear of the grisly plateau and had paid the penalty. Kane's teeth came together with a vicious snap which ordinarily took the place of profanity with him. He was stung by the thought of fleeing so long from a single enemy. No wonder that enemy had followed so cautiously, waiting until dark to attack. But, asked Kane, why had the akaana seized the black man instead of himself – and why had he not been attacked by the bat-man who alighted in his tree that night?

The cannibal was bleeding, Goru answered; the scent called the bat-fiend to attack, for they scented raw blood as far as vultures. And they were very wary. They had never seen a man like Kane, who showed no fear. Surely they had decided to spy on him, take him off guard before they struck.

Who were these creatures? Kane asked. Goru shrugged his shoulders. They were there when his ancestors came, who had never heard of them before they saw them. There was no intercourse with the cannibals, so they could learn nothing from them. The akaanas lived in caves, naked like beasts; they knew nothing of fire and ate only fresh raw meat. But they had a language of a sort and acknowledged a king among them. Many died in the great famine when the stronger ate the weaker. They were vanishing swiftly; of late years no females or young had been observed among them. When these males died at last, there would be no more akaanas; but Bogonda, observed Goru, was doomed already, unless – he looked strangely and wistfully at Kane. But the Puritan was deep in thought.

Among the swarm of native legends he had heard on his wanderings, one now stood out. Long, long ago, an old, old ju-ju man had told him, winged devils came flying out of the north and passed over his country, vanishing in the maze of the jungle-haunted south. And the ju-ju man related an old, old legend concerning these creatures – that once they had abode in myriad numbers far on a great lake of bitter water many moons to the north, and ages and ages ago a chieftain and his warriors fought them with bows and arrows and slew many, driving the rest into the south. The name of the chief was N'Yasunna and he owned a great war canoe with many oars driving it swiftly through the bitter water.