The Saltmarsh Murders (26 page)

Read The Saltmarsh Murders Online

Authors: Gladys Mitchell

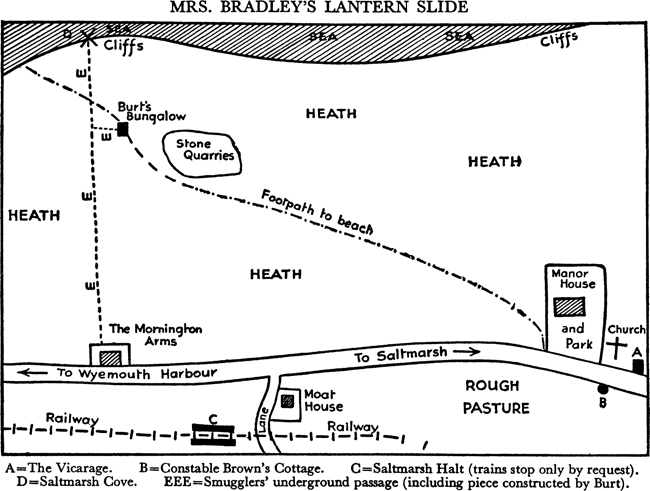

“To-night I am going to show you the mistakes made by persons who had a hand in committing the Salt-marsh murders. At the end of my lecture I think that everybody in this hall will know the author of the deaths by violence of Margaret (Meg) Tosstick, of this village, and Cora McCanley, of the Bungalow, Saltmarsh Quarries. In front of you on the screen there is a rough plan of the scene of operations. I will explain what is meant by the various markings on that plan.

“To your extreme right, as you look at the screen, you will see a square. That represents Saltmarsh vicarage. Moving your gaze from right to left, you will perceive a cross which represents the church, and then a rectangle, which represents the residence of Sir William Kingston-Fox. I think you call it the Manor House. To the left of the plan there is another square, rather larger than the first. This is the Mornington Arms Hotel. The main road through the village of Saltmarsh is represented by a broad ribbon-like marking running below all the above-named buildings. On the other side of this road and almost opposite the church, you will see a much smaller square than either of the others. This represents the cottage of Constable Brown. Up a short and narrow side turning, a mere lane, further to the left and on the same side of the main road as Constable Brown's cottage, there is a rectangle which marks the site of the Moat House, the residence of Mr. and Mrs. Gatty.

Â

“At the top of the plan you will see a wavering line which represents the sea coast. The small cross there marks the cave known as Saltmarsh Cove. It is an old smugglers' hole, as most of you know, and an underground passage was constructed in about the year 1704 to connect the Cove with the Mornington Arms, which was then called the Pagg and Nancy, after a famous smuggler and his sweetheart. This passage to the Pagg and Nancy, which was made to meet the problem of getting contraband liquor to the inn in the old smuggling days, is represented by a closely-dotted line and the dotted line which leads from the Cove, past the Bungalow, where Miss McCanley lived, to the edge of

Sir William Kingston-Fox's estate, represents the footpath which leads past the stone quarries. An arrow, pointing along the coast to your right, would show direction of the current called Deadman's Drift.

“I shall not have very much occasion to refer to the plan during the course of my lecture, but I am going to leave it up in front of you, so that you may the more easily follow the movements of the persons about whom I have to tell you.”

There was a slight pause. Somebody shuffled his feet; a chair creaked as somebody changed her position; somebody cleared his throat. They were nervous, not fidgety, noises. The whole atmosphere reminded me of a fearful row at school once when the head pi-jawed us before he expelled a chap. There was the same tenseness, the same feeling of wondering how much the old man knew about one's own sins ⦠Mrs. Bradley braced her belt about her, so to speak, and having fired off the sighting shots, as it were, got down to business.

“I warn you,” she said, “that you will find my next remark very unpalatable. But I am going to ask you to receive it patiently and accept it as the truth. It seems to me that the whole Mystery of Saltmarsh, as the newspapers have called it, rests upon the fact that this unpalatable truth which I am going to utter was not recognised, even by the police, for an important clueâwhich means a key, you knowâto the dreadful things which have happened here since the beginning of August. Briefly, your comrade, and my young friend, Robert Candy, may have been the agent who strangled Margaret Tosstick on the evening of August Bank Holiday, August 3rd.”

There was an uncomfortable rustling, but nobody said a word. She continued:

“I am calling my lecture, âMistakes the Murderer Made.' I am not referring to Robert Candy, but to the murderer of Cora McCanley and the murderer of Meg Tosstick.”

I heard Burt whisper a terrible oath, but Mrs. Bradley's voice was hypnotic, and, shifting his great shoulders uneasily against the back of his chair, which was next to mine, he settled down again into immobility.

“The first mistake the murderer made,” said Mrs. Bradley, “was in arranging for Robert Candy to kill Meg Tosstick eleven days after her baby was born. His second mistake was that the baby was never seen, apparently, except by Mrs. Lowry, who had acted as midwife at the birth of the child; therefore several wild rumours, which circulated about the village very freely and were believed by certain very credulous and rather foolish people, could not be disproved, except by Mrs. Lowry, and she seems to have been sworn to secrecy.”

I thought of Mrs. Coutts and the underlying causes of the siege of the vicarage. I thought, too, of the girl's ruin being laid at the door of Sir William Kingston-Fox. I could feel people trying to pierce the blackness in which Mrs. Lowry sat, invisible.

“The murderer's third mistake,” said Mrs. Bradley, “was to kill his second victim on the day after the first murder. His fourth lay in refusing to allow Cora McCanley to go to London and do something at the London terminus silly enough or flighty enough, or

daring enough to make certain that she would be noticed. As soon as it was found impossible to ascertain whether Cora McCanley had ever arrived at the London terminus to which she took a ticket on that particular Tuesday, it became a matter for consideration whether she had ever actually left Saltmarsh. Then the police discovered that she had never joined the theatrical company which was her supposed objective. Thus it became increasingly conjecturable whether she had ever left Saltmarsh. From that, the question arose, âWhere was she, if she were still in Saltmarsh?'

“That question was answered by the discovery of her body in Meg Tosstick's grave. It was mere chance that that melodramatic action of changing the bodies did not count as another of the murderer's mistakes. Suppose that the body of Meg Tosstick had been found before we came to the conclusion that the name of the buried girl did not correspond with the name on the tombstone! The police would then have exhumed the body and discovered that it was not Meg's but Miss McCanley's, and that it also had met death by strangling. I have made various tests, and I discover that flotsam thrown into the water opposite Saltmarsh Cove and thereabouts is washed up two or three days later on to the spit of land known as Dead Man's Reach, some two miles down the coast westwards; that is, to the right of that rough plan. By the most extraordinary coincidence, the tides, the wind and the awful weather must have combined to take the body out to sea. It has not yet been found; or, if found, it has not yet been identified. The murderer may have worked this out.

He is a clever person. But I think he was taking a big risk. His argument probably ran something like this:

“âCora McCanley has disappeared from Salt-marsh. Some interfering busybody has put the police on her track. So if I throw her body into the sea and it gets washed up and identified, where am I? On the other hand, if Meg Tosstick's body gets washed up, the chances are that as no description of Meg has been circulated, the body won't be identified, particularly as it will have been in the sea for a day or two.'

“So he risked it, and it came off; and, but for the most fortuitous set of circumstances”â(thus Mrs. Bradley on her own marvellous bits of reasoning and deduction!)â“it would have continued to come off, at any rate for several months. By that time, any possible connection of the murderer with the crime would have vanished.

“Now, those fortuitous circumstances were as follows:

“You remember, perhaps, that I stated the murderer's first mistake had been to cause Robert Candy, for whom, please, I feel quite as much sympathy as you do, to kill his sweetheart eleven days after her baby was born. Now, that kind of crime for that kind of reason is almost unheard-of. There was no earthly reason, so far as one could see, why Bob Candy, having familiarised his mind with the fact that his sweetheart had betrayed him, and having shown neither scorn nor resentment when he heard that the child was born, should suddenly, without apparent warning, seize an opportunity to strangle the girl he had loved. It was so unreasonable an action that one felt an amazing

amount of curiosity about it. One weighed the known facts, wondering all the time whether the police had not arrested the wrong man. But the more one looked at the facts, the more apparent it became that Bob was probably the technically-guilty person.”

This time there was an interruption. From the second rowâI know where it was, because it came from immediately behind meâMrs. Gatty's unmistakable voice said menacingly:

“That will do, Croc. That will do. The pig shall lie down with the young she-bear; she was no longer Lady Clare; and all the beasts of the field shall be blind for the space of two moons. I, Moto-Kari, the wise owl, have spoken it. Go away, you boys!”

She was prodded into silence by old Gatty, I suppose. Anyway, she shut up, after that, and Mrs. Bradley was able to continue her remarks. In five minutes, or less, the audience was as much absorbed in what she was saying as though there had been no interruption. Mrs. Gatty went to sleep, I believe. I could hear her deep, rather noisy breathing, behind me, and once old Gatty grunted as though her head on his shoulder was becoming too heavy to be blithely and carelessly supported.

“It was obvious from the first,” Mrs. Bradley continued, “that poor Meg Tosstick was being terrorised, presumably by the father of her child. Now, the biggest mistake that the murderer of Cora McCanley (and the

responsible

murderer of Meg) made, was this. He changed his habit of mind. When a man or woman changes a mental habit, one of two things has happened. Either there is an ulterior motive for that change, or else that

person's spiritual outlook has completely altered. The change to which I am referring was a change from meanness to generosityâperhaps the most unusual change which ever takes place in the nature of man. It is, indeed, such an unusual change that we psychologists always regard it with what I consider to be a very legitimate and comprehensible amount of doubt and suspicion when it is brought to our notice.

“Now, I brought to the investigation of these Salt-marsh crimes an open and unprejudiced mind. I did not know any of you, when I first came to stay here, with the exception of Sir William Kingston-Fox and his daughter. The fact that I knew nothing about you was more of a disadvantage than an advantage, because it meant that almost all the information about you which it was possible for me to acquire had to be acquired from other people, many of whom showed considerable prejudice and bias in what they told me. A good deal of the most valuable information now in my possession was given to me without the donors being aware of the importance of their remarks. It might be of interest to some of you to be given a few examples of the kind of thing I mean. Let us take, for instance, the matter of that secret passage which connected the Cove with the Mornington Arms. You may, or may not know, that the end of the passage which terminates in the cellars of the Mornington Arms is now blocked up. Mr. Lowry informs us that it was blocked up when he succeeded his father at the Mornington Arms, and that he remembers, very vaguely, its being blocked up when he was a tiny boy. Now when I tell you that I know for a fact that Cora McCanley was

murdered in her own home, and that Mr. Burt, for a joke, once spent several months tunnelling a transverse to that tunnel so that he could reach the Cove underground from his bungalow if he wished to do so, you will see that it was of importance to Mr. Lowry to prove that the exit at his end was blocked. But did Mr. Lowry prove it? No. The supposition that that exit was, and had, for years and years been blocked up, came out quite casually when I was talking with one of Sir William Kingston-Fox's servants some time ago, and this supposition was proved to be a fact only quite recently, after police investigations.

“To take another instance:âthere was the affair of Mr. Burt and the vicar. You remember that the vicar was attacked by two men with blackened faces whom he supposed were poachers. It was entirely fortuitously that it came to my notice that Mr. Burt kept a negro manservant, and so I traced Mr. Burt's little joke to its perpetrator. So far as the murder of Meg Tosstick was concerned, that incident was of primary importance, because it then suggested to me that Robert Candy was goaded into murdering Margaret Tosstick by hearing that she had been seduced by Burt's negro servant and had borne a half-breed baby.”

There was a sudden violent interruption. Foster Washington Yorke stood up, I should say, and his chair fell back on to the person behind, who shrieked.

“Dat's a lie! Dat's a lie!” shouted the negro, apparently, by the sound, trying to fight his way to the front of the hall. Several people tried to collar him, of course. At least, judging from the row that was going on, they did. Suddenly in the midst of the tumult the

door nearest to me opened, and some biggish person slid out without a sound. I felt a terrific draught from the open door, but I could not identify the slinking figure. Mrs. Bradley had a megaphone with her, I should think, because the village hall was suddenly filled with her voice, amplified and booming. It said, in a tone of absolute confidence and authority: