The Sahara (3 page)

Authors: Eamonn Gearon

Tags: #Travel, #Sahara, #Desert, #North Africa, #Colonialism, #Art, #Culture, #Literature, #History, #Tunisia, #Berber, #Tuareg

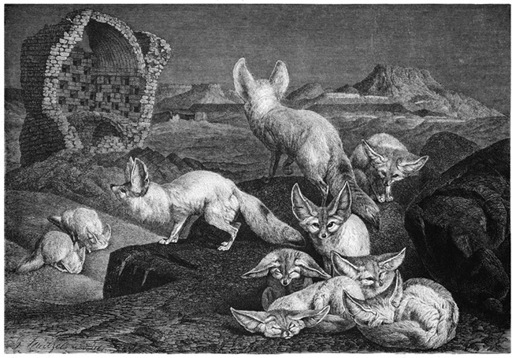

Many ground-based animals share the common characteristic of outsized ears, which allows them to thrive in the desert. Most famous is the Fennec, a small fox-like rodent. These cartoonish appendages are also prominent on the desert fox, desert hare and desert hedgehog. Apart from providing them with an auditory advantage while hunting insects, the ears also allow for the dispersal of heat, thereby allowing the animals to survive.

Unfortunately for naturalists, the larger the desert mammal the rarer it is and, therefore, the slighter the chance of seeing one. The tracks of increasingly rare Saharan gazelle or antelopes such as the Oryx and addax may be found but one can spend a lifetime without seeing the beasts themselves. Conversely, among some of the more plentiful desert reptiles, one must hope that any encounter is not too unexpected, scorpions in particular being attracted to the warm bodies of sleeping people. Hiding is also the specialized hunting technique of the horned viper, which lies in wait for its prey just beneath the sand, its eponymous horns alone visible above the surface. Woe-betide the barefooted wanderer who steps on this denizen of the desert. Its venom might not be lethal but its bite will do more than put one in a bad mood.

Whether gazing down from the peak of a mountain or dune, or looking up from below sea level, the Sahara is a land of enormous geographical variety and some beauty, much of which is unknown or too often overlooked. Travelling at high speed may create the illusion that one has seen a great deal of the desert, but in reality one has seen nothing at all. Of nowhere is this truer than the Sahara, which deserves to be discovered over time.

The long-eared Fennec Fox

Whales in the Desert

‘‘And God said, Let the waters under the heaven be gathered together unto one place, and let the dry land appear: and it was so. And God called the dry land Earth; and the gathering together of the waters called the Seas: and God saw that it was good.”

Genesis, 1:9-10, King James Version

If asked which words one associated with the Sahara, only the most dedicated surrealist might be expected to offer “whale”. “Camel” and “sand” are far more likely choices. But in fact the surrealist would not be entirely wrong-albeit harking back millions of years to the desert’s pre-prehistory. This arid expanse hardly seems the ideal habitat for whales but long before the camels moved in (between 3000 and 3500 years ago, making them the most recent mammalian arrival) it was actually teeming with all sorts of marine life. In a period that one can think of as the Sahara’s pre-pre-history, a large part of the landmass that would eventually become the largest hot desert on earth lay submerged beneath a vast body of water, the Tethys Sea. Thus, the whale was a resident of what was to become the Sahara.

The sea has long vanished. Today there are only a small number of oases scattered across the northern third of continental Africa which the Sahara covers, mere specks on the map where water allows life in the middle of an otherwise seemingly lifeless and desolate landscape. Yet evidence of the Sahara’s watery past can be seen in numerous places, with more fossil discoveries being made every year by marine palaeontologists and archaeologists working in the desert. One of the most impressive sites of fossil remains to be found anywhere in the Sahara also happens to be one of its most accessible, situated as it is less than a hundred miles southwest of Cairo. Wadi al-Hitan, the Valley of the Whales, covers one hundred square miles and contains one of the world’s most important collections of fossils of early whales, which is why in 2005 Unesco added it to its list of World Heritage sites.

The majority of the hundreds of fossil remains found in Wadi al-Hitan are examples of the proto-whale known as the Basilosaurus, or “King Lizard”, which belonged to a long extinct sub-order of whales called Archaeoceti alive and swimming approximately forty million years ago. With an adult Basilosaurus growing up to 69 feet long, they were not only noticeably smaller than today’s Blue Whales (up to 115 feet) but also a great deal sleeker, with an elongated body more reminiscent of an inflated eel than a bulbous whale.

Whale skeleton at Wadi al-Hitan

Explaining its decision to grant World Heritage status, Unesco explained that “Wadi Al-Hitan is the most important site in the world to demonstrate one of the iconic changes that make up the record of life on Earth: the evolution of the whales.” Easily discerned in the fossil record, one can see whales in one of the last stages of their evolution, complete with tiny limbs sticking out from the area of their rear flanks. While complete with moveable joints and toes, these small “legs” are too small to have been of any practical use in supporting the immense body weight of the Basilosaurus. Instead, these vestigial limbs are said by palaeontologists to be evidence of the unusual reverse evolution of whales, wherein they returned to a marine existence having previously been land-based mammals.

It might seem too long ago to be worth considering, but the Sahara’s marine past and the seas retreat is every bit as important as its later, desiccated periods. It is believed that the Tethys Sea evolved out of the mega marine body known as the Tethys Ocean. This super ocean existed before continental drift had fashioned shorelines into the shapes familiar to us today. The terms Tethys Ocean and Tethys Sea are frequently and frustratingly used interchangeably, in spite of their being at one time distinct bodies of water. This is perhaps forgivable, since many questions related to ancient geology are still, no pun intended, evolving. But the sea is what we are interested in when considering the time when our Egyptian whales died. This “smaller” body of water encompassed the whole of the modern Mediterranean basin, southern Europe, northern Africa and a water bridge that covered Anatolia and the Levant and stretched east through Iran and Iraq, covering contemporary northern India.

Only named in the last decade of the nineteenth century, the Tethys Sea took its name from the Titan goddess, one of those deities who, according to Greek mythology ruled over heaven and earth during the so-called Golden Age, before they were vanquished by the Olympians, that younger generation of upstart gods who made their home on Mount Olympus. As the goddess of fresh water, Tethys was believed to be the source of rivers, springs, streams, fountains and rain clouds. Tethys was thus responsible for nourishing the earth. Referring to “Tethys our mother”, Homer, in his eighth-century BCE epic the Iliad, places Tethys at the heart of the literary history of the Sahara even before the desert existed. The wife of Oceanus, Tethys was able to draw water from her husband, before passing it on to mankind through underground springs, which appeared in the world as if by magic. Among the forty or so children born to Tethys were such familiar names as Asia, Styx (the river that marks the boundary between earth and the underworld) and a son Nilus, the god of the Nile.

In the 1950s and 1960s, French palaeontologists and geologists working in the deserts of central Niger independently discovered teeth and other fossil remains of another gargantuan prehistoric marine dwelling animal in the valley of Gadoufaoua, which in the local Tuareg language means “the place where camels fear to go”. A fuller picture of this mammoth marine creature was not completed until additional, large-scale discoveries were made in the late 1990s by Paul Sereno from the University of Chicago and his team. Named

Sarcosuchus imperator

by scientists, the animal is better known by its media tag: Supercroc. A

Sarcosuchus imperator

jawbone discovered by the team measured an impressive six feet on its own. Only distantly related to modern crocodiles, the ancient behemoth, which lived some 110 million years ago, grew up to forty feet long and weighed between eight and ten tonnes. The death knell sounded for Sarcosuchus, Basilosaurus and similar water-dependent mega-fauna between 30 and 26 million years ago, when the Sahara went through a major climatic change, resulting in a more tropical and drier environment.

In order to get to the formation of the Sahara as desert, needs force us to jump forward some 24 million years into the Pleistocene Epoch or “most new age”, the older of two epochs in the Quaternary Period, the period through which we are still living. By 1.8 million years ago the outline of the continent of Africa was clearly recognizable. The epoch was characterized by repeated periods of widespread glaciation and thaw, or interglacials, in which violent temperature fluctuations led to the extinction of most species of megafauna, including the sabre-toothed tigers and the mammoth. It also saw the extinction of horses and camels in their home continent of North America. In place of the big beasts, large numbers of smaller animals including mice, birds and cold-blooded species emerged, better suited to the new prevailing conditions. But it was not just small fauna that benefited from the change in the weather, because it was during this time that modern humans evolved, from

Homo erectus

, upright man, into

Homo sapiens

, so-called wise man, just 200,000 years ago.

Our recognizably human ancestors quickly set themselves apart from their predecessors, developing most of those social characteristics one still associates with mankind. No longer content just to eke out an existence, people made the great leap to living in societies. Evidence of early human societies can be found across the Sahara in many forms; in tools and products fashioned by these tools, from the remains of animals killed and skinned to the building of shelters and the digging of graves and the first human burials. As if all of these accomplishments were not enough, it was also during this period that our ancestors in the Sahara, as elsewhere, moved ahead in other, profoundly moving ways by mastering the use of language and in creating works of art.

The Green Sahara

Having established that whales used to swim in a sea that once covered what is now the Sahara, readers should have no difficulty accepting that at another point in time it was a green and pleasant land. Great fluctuations between wet and dry weather occurred in the Sahara from roughly 10,000 to 4000 BCE, the period rightly known as the Green or Wet Sahara. Indeed, to talk about the “Sahara’ is somewhat misleading, as the desert region that now fits this description did not, in a sense, exist at this time.

For thousands of years, landscapes that are today extremely inhospitable used to abound with a rich variety of flora and fauna. Where now there exists a relative paucity of biodiversity there were once well-watered places supporting a large number of productive environments, including rainforests and grassland as well as marshes and other wetlands. Water was so abundant that it offered a home to such marine animals as the hippopotamus, not to mention innumerable species of fish. The savannah was covered in grasses that provided for large mammals such as the elephant, giraffes and gazelle, which were in turn prey for the lions with which they shared the plains. Tibesti, Ennedi and Air, today barren and rocky ranges, were instead mountains blanketed in trees - oak, pine, olive and walnut providing fruit for a multitude of animal populations. Indeed, the wealth of flora and fauna that once existed accounts for the massive reserves of oil and gas that are found under the Sahara today. Naturally, this Eden-like Sahara was just as favourable to emerging human societies.