The Sahara (18 page)

Authors: Eamonn Gearon

Tags: #Travel, #Sahara, #Desert, #North Africa, #Colonialism, #Art, #Culture, #Literature, #History, #Tunisia, #Berber, #Tuareg

Far less ostentatious in size or construction material, the so-called Rosetta stone uncovered by workmen digging in the Nile Delta in July 1799 remains the most important ancient relic exported from Egypt. Shipped back to London in 1802 aboard the captured French frigate

L’Egptienne

, renamed HMS

Egyptienne

, the stone shows the same text in three languages: Egyptian hieroglyphic, Egyptian Demotic and classical Greek. Translation of the Greek was straightforward but the Egyptian languages proved more taxing, with two scholars, Thomas Young and Jean-Franois Champollion, working for years on the puzzle and finally completing the translation in 1824. Breaking the code of the ancient Egyptian texts allowed a flood of translations to be made of as many other Egyptian texts as scholars could manage, a task that remains incomplete today.

Between them the African Association and Napoleon’s army of scholars had made an impressive start to achieving their shared missions of exploration and discovery, and although neither completed their self-imposed task, far more important was the impact on those who followed them. For the rest of the nineteenth century the Sahara became the plaything of Britain and France - European rivals who watched each other so carefully that they almost totally overlooked the local populations who, it would become clear, had their own ideas about these foreign interlopers.

Further Horizons - Exploration and the European Land Grab

‘‘And if we may regret that the liberty of the Bedouins of the desert has been destroyed, we must not forget that these same Bedouins were a nation of robbers.”

Frederick Engels, after the 1847 capture of the Algerian resistance leader, Abd el-Qadir

If eighteenth-century exploration marked Europe’s first forays in the Sahara since ancient times, the following century was concerned with extending those footholds to the furthest horizons. Spurred on by the reports and achievements of the African Association’s explorers, subsequent generations produced similar justifications for their Saharan expeditions: the discovery and opening of new markets; the pursuit of scientific knowledge and a need to overcome geographical ignorance; the missionary imperative; and a growing sense of imperial entitlement to other people’s lands. None of these was mutually exclusive: geographical discovery, trade and missionary activities frequently complemented one another. Of the litany of validations offered only imperial entitlement was inherently detrimental to local interests.

Some who believed the European cultural model was inherently superior to all others used the theory of evolution, as propounded by Charles Darwin, Alfred Wallace and others, to prove this. While the theory was itself both a revolutionary and blameless work of science, it did produce in some readers a powerful sense of their natural superiority over foreign places, typically those populated by people of a different colour who did not have modern weapons. The pursuit of pure science or honest trade was commendable, but such potentially laudable goals had always been subject to the demands of more covetous appetites.

The passing of the Slave Trade Act by parliament banned, but did not stop, the slave trade in the British Empire. The act only made the trade in slaves illegal, not the institution of slavery

per se

: slavery itself did not become illegal until the 1833 Slavery Abolition Act. In the case of the United States, similar legislation was not passed until 1865. While the Royal Navy patrolled the seas, looking for any of the many ships breaking the law, they were naturally unable to do anything about the overland transportation of slaves. According to one source, each year between 1800 and 1860 approximately 10,000 slaves crossed the Sahara. Upon reaching the north coast, they would be sold at the slave markets that were a feature of most port cities, the largest of which was in Tripoli. The slaves were then shipped by their new owners to various parts of the Ottoman Empire, which still included the Balkans at this time, and beyond.

Although to modern eyes the abolition of slavery was a wholly good thing, those Africans, Arabs and Europeans alike who had made a living through it now had to find other commodities in which to trade, and this often meant finding and opening new markets. As a result there was a new impetus to explore the African interior, until then among the least-known places on earth. Suddenly the task of penetrating the Sahara and sub-Saharan Africa became an obvious and urgent endeavour. It was in this atmosphere that the major intra-Saharan expeditions of the nineteenth century took place.

One of the most important of these was a five-year mission sponsored by the British government that set out from England in 1822. The expedition’s leader was Walter Oudney (1790-1824), a Scottish doctor, sometime naval surgeon and naturalist. Travelling with him were Hugh Clapperton (1788-1827), like Oudney a Scottish-born naval officer, and Dixon Denham (1786-1828), a British Army officer from London who had fought against Napoleon in Spain and at the Battle of Waterloo.

The mission proposed by the government was to accurately determine and map the course of the River Niger, which at least since Park’s journey was known to run eastwards. If it seems strange that two of three officers on this Sahara mission were navy men, it should be remembered that they were given the task of charting a waterway and establishing how much and what parts of it were navigable. Perhaps it also makes sense, then, that the officers were accompanied by a shipbuilder, William Hillman, who was in charge of the expedition’s stores.

Having sailed to Tripoli, the expedition entered the Sahara, the officers on horseback accompanied by 32 camels, a pair of mules and a couple of dogs. Notably, they did not travel in disguise, as certain explorers both before and after did. Such an open display of their foreignness emphasized not just that they were well-armed, but also underlined the new-found confidence Europeans felt in pressing forward into the Sahara. As Clapperton proudly wrote in his journal, “[we] were the first English travellers in Africa who had resisted the persuasion that a disguise was necessary, and who had determined to travel in our real characters as Britons and Christians, and to wear, on all occasions, our English dresses; nor had we, at any future period, occasion to regret that we had done so.” As events transpired, it became clear that the greatest threat to the men’s safety came not from angry native tribesmen but from among themselves.

Whatever else the Bornou (sic) Mission, as it was called, became known for it was sadly not for any collaborative spirit among its main participants. Oudney, Clapperton and Denham were men of wildly differing temperaments. The authorities in London had not thought it important to consult the men about their travelling together, and none of the three relished the prospect when ordered to do so, each wanting to be in charge of his own destiny. They failed to reach an equitable division between the civil and military aspects of the mission, and disliked taking orders from one another.

The further into the Sahara they travelled the worse the feuding became. At one stage Denham made the almost certainly unsubstantiated allegation that Clapperton was conducting a homosexual relationship with - heaven forbid! - one of their native servants. The increasingly acrimonious disputes meant that Denham and Clapperton stopped talking to one another, only communicating via official letters, sent back and forth from their respective tents. These missives would be hilarious if found in a novel, rather than during a dangerous mission in a harsh and alien environment. One letter from Clapperton, dated “Tents, Jan 1st, 1823”, signals his unwillingness to take orders from Denham, a naval officer, whose jurisdiction over him he did not accept: “Sir, I thought my previous refusal would have prevented a repetition of your orders.” Clapperton goes on to explain why he will continue to ignore any further orders, signing off, “I have the honour to be Sir, Your most Obedient humble Servant, Hugh Clapperton.” Their first New Year in the Sahara was not to be ushered in to the strains of

Auld Lang Syne

.

Against all odds and in the face of the complete collapse of any rapport between the officers, the mission was a greater success than it had any right to be. Having made a successful north-south crossing of the Sahara, they discovered a large lake on the desert’s southern shores. In spite of Denham’s hope to see it named Lake Waterloo, it was to become known as Lake Chad, from a word in the local Bornu language,

tsade

, which means a large body of water; so “Lake Lake” was christened.

Oudney died shortly after this, halfway between Lake Chad and Kano, Nigeria, where he was heading with Clapperton. Clapperton pressed on alone to the Sokoto, a tributary of the Niger from which he was now just five days distant. But in Sokoto - the newly established capital of the Fulani’s so-called Sokoto caliphate - the sultan forbade him to go any further. For one thing, the local rulers were still active in the slave trade and were fearful of any British interference in this lucrative business. Unable to find a guide willing to break ranks with the ruler’s orders, he was forced to retrace his steps to Lake Chad.

While Clapperton was absent, Denham had unsuccessfully attempted to circumnavigate Lake Chad, and had instead headed back to Tripoli. Clapperton too made the journey back to the coast, arriving in Tripoli in January 1825 and then returned to England to make his reports to the government and the African Association, which remained, until its incorporation into the newly formed Royal Geographical Society in 1831, a significant force in Saharan exploration.

Caillie, Barth and Rohlfs

Among the early solo explorers of the Sahara, Rene-Auguste Caillie (1799-1838) holds a special place as the first European to reach Timbuktu and return alive. Before him, the fate of the few western travellers who made it to the city, dying or being killed on the return journey, resulted in a paucity of information regarding Timbuktu, which served to highlight the city’s extreme isolation in the desert over which these pioneering explorers roamed.

By his own admission, Caillie was inspired to a life of exploration after reading

Robinson Crusoe

, Daniel Defoe’s novel about a shipwrecked sailor on a desert island. Such are the seemingly small events that unveil kismet. Caillie started his trans-Saharan journey from Freetown, travelling through Conakry, Guinea and onto Tieme and the upper reaches of the Senegal river. During the four months he spent there he suffered from a more typically naval affliction, scurvy: an inauspicious start to his adventure. Once recovered, Caillie set out alone for Timbuktu, travelling in trading canoes along the Senegal and Niger rivers. En route, a further bout of illness saw him stranded for a further five months.

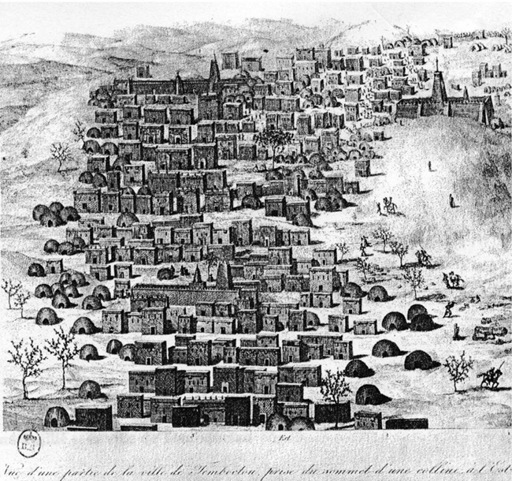

Timbuktu in 1828, from Caillié’s book

Unlike Clapperton, Oudney and Denham’s larger, better-equipped and altogether fractious expedition, Caillie travelled in disguise, claiming to be an Egyptian Arab on his way home from Senegal, where he said he had been taken by the French. Having recovered from his second lengthy spell of sickness, he journeyed on to Kabara, Timbuktu’s port town on the Niger, from where he crossed the final five miles overland to Timbuktu. Caillie arrived at the “lost” city on 20 Aprill828, realizing the dream of countless explorers eleven months after leaving Freetown.

Caillie’s account of his arrival at Timbuktu is, naturally enough, filled with the joy at his safe arrival, achieving a target that had occupied him for years. He records the moment thus:

At length, we arrived safely at Timbuktu, just as the sun was touching the horizon. I now saw this capital of the Soudan, to reach which had so long been the object of my wishes. On entering this mysterious city, which is an object of curiosity and research to the civilised nations of Europe, I experienced an indescribable satisfaction. I never before felt a similar emotion and my transport was extreme. I was obliged, however, to restrain my feelings, and to God alone did I confide my joy.

Having got over his initial euphoria, Caillie, an honest observer, goes on to describe the rather commonplace surroundings of the desert town: “I looked around and found that the sight before me, did not answer my expectations. I had formed a totally different idea of the grandeur and wealth of Timbuktu. The city presented, at first view, nothing but a mass of ill-looking houses, built of earth.” It was clear to Caillie that the legends about a city of gold were just that. Nearly three centuries after the city’s heyday, Timbuktu was essentially a great disappointment.