The Runaways (23 page)

Authors: Elizabeth Goudge

He looked so tall and strong and angry as he spoke that Nan believed he could and would do just what he said, but Uncle Ambrose, looking suddenly just as tall and strong and angry, eyed him with beetling brows and said severely, ‘Vengeance, sir, is cruel, stupid, useless, and vulgar. Remember that when you return to the world. Well, Nan and I must bid you farewell. I will, if I may, do myself the honour of waiting upon you again tomorrow morning.’

‘May I come down to the woods with you, sir?’ asked Daft Davie, as meek now as a scolded child. ‘Then I can go on talking,’ he added happily.

So the three of them went down the valley together,

climbed over the Lion’s paw and stood looking down at the rustling sea of green leaves below them, and up into the unendingness of the golden sky above, where invisible larks were singing, and suddenly Daft Davie began to sing again, his song ringing out over the tree tops. When the song ceased echo answered from down below the green leaves, a deep echo like a voice singing under the sea. Uncle Ambrose and Daft Davie listened in amazement, but Nan said, ‘It’s not echo, it’s Moses singing in the yard by the back door.’

‘Moses?’ asked Daft Davie. ‘Moses?’ and he looked so bewildered that Uncle Ambrose changed the

conversation

by saying, ‘Sir, you must be attached to these woods.’

‘They are mine,’ said Daft Davie simply, ‘and all the creatures in them.’

Uncle Ambrose hastily led the way down the rocks. They were nearly at the bottom before Nan said, ‘Look!’ They stopped and looked and down in the wood below was William Lawson, bending down and doing

something

at the foot of a tree. He was setting snares. Daft Davie flung back his head and roared like a lion. He looked like a lion too, with his tangled mane of hair, a terrible infuriated beast whose roaring turned to a spate of furious words that made William Lawson look up and then stare as though turned to stone, terror and amazement on his face.

Uncle Ambrose had hold of Daft Davie by his lion’s mane. ‘Stop that!’ he commanded. ‘Don’t swear. Sing!’

With a tremendous struggle Daft Davie strangled his roars and sang. And from below came the deep rumble

of Moses’ singing, and from the woods the voices of children.

Down with all hard-hearted naughty scoundrels,

Their traps and snares.

Down with those who plot the death of squirrels,

Rabbits and hares.

Shame on those who harm the stripy badger

And hunt the fox.

Shame on all ill-wishing jealous witches

And black warlocks.

Run from our green lanes and hills and meadows,

From moor and wood,

Or else speak truth, be affable and kindly,

Harmless and good.

Glory for the fleeing of the shadows,

The rising sun.

Glory, children, glory alleluja,

For night is done.

Glory, glory seemed to ring from every corner of the wood and William Lawson turned and ran. And from hidden places in the woods came Emma and Frederick, Eliza and the bulldog, and they too were running for their lives. Yet not one of the unseen singers had moved, or did move until the woods were free. Then they appeared through the trunks of the trees, Moses, Abednego, Ezra, Robert, Absolom, Timothy, and Betsy.

‘I said these children were to stay at home,’ said Uncle Ambrose severely to Ezra.

‘I be sorry, sir,’ said Ezra. ‘I feared some ’arm might come to you. An’ the children ’ad the right to be ’ere.’ Then he looked up at Daft Davie. ‘Glad to ’ear your voice, sir,’ he said.

But Daft Davie was not listening to him or even looking at him. He was looking first at Moses and then at Abednego and his face was working strangely, as though he were trying to remember something. Uncle Ambrose put his hand on his shoulder. ‘Go back to your house, sir,’ he commanded. ‘Go back to the cave and possess your soul in patience. Tomorrow morning I will come to you and all that now seems strange will be made plain.’ Daft Davie turned round and went slowly back, for when Uncle Ambrose commanded everyone always obeyed. Then Uncle Ambrose turned to Moses, who was staring at Daft Davie’s retreating back with as much bewilderment as Daft Davie had stared at him. ‘Moses, take me back to Lady Alicia. I have a great deal to tell her, and to tell you also. Ezra, take the children home. Confusion is at present great, but undoubtedly it is a happy hour.’

They all tramped joyously down through the woods, parting at the stableyard. Uncle Ambrose, Moses, and Abednego went into the house and Ezra, the children, and Absolom went singing through the garden and the shrubbery. They did not stop singing until they reached the green.

‘My stars!’ ejaculated Ezra.

‘What is it?’ asked Nan.

‘Look there,’ said Ezra. ‘An’ stand back. Keep out o’ sight.’

They obeyed him and looked in the direction of his pointing finger. The Bulldog sign outside the inn had disappeared and the bar from which it had hung was empty, with an equally empty stepladder standing beneath it. As they gazed in stupefaction, William Lawson came out of the inn carrying a brightly coloured picture, followed by Emma and Frederick the cat. It was Emma who nimbly mounted the ladder and William handed the picture up to her and she hung it where the Bulldog had been. Then she came down the ladder again and William carried it back inside the inn. Emma and Frederick remained where they were, looking up at the new sign.

It represented a magnificent peregrine falcon with a creamy speckled breast, night-dark wings, and curved scimitar beak. Behind him was a sky of brilliant blue and the hand that held him up into the sunshine was gloved in scarlet.

‘’Tis the old Falcon!’ whispered Ezra in fierce tones. ‘The sign that was there afore Squire Valerian went away. William Lawson took it down, blast ’im! ’Tis the old sign come back.’

Emma turned round and saw Ezra and the children standing by the gate. She looked at them with a most charming expression on her face, smiled sweetly and curtsied to them. Then she walked slowly and serenely to her shop with Frederick, a very meek little cat, trotting at her heels, went in and closed the door quietly behind her.

Ezra breathed a great sigh of relief and said, ‘’Tis gone!’

‘What’s gone?’ asked Timothy.

‘The wickedness,’ said Ezra. ‘All the badness that’s been in this village for many a long year. An’ sorrow an’ partin’ with it. ’Tis gone.’

‘Emma’s still here,’ Nan reminded him.

‘She won’t do no more ’arm,’ said Ezra. ‘’Er spells be burnt an’ she won’t do no more ’arm. ’Angin’ up that falcon was ’er sign to us that she knows she’s beaten. She won’t do no more ’arm. Glory glory alleluja!’

They went singing down the hill to the Vicarage and then straight up the garden to the beehives where they stood in a row and bowed and curtsied. The

marvellous

light was now so brilliant that they all turned gold while they did it. ‘Madam queens an’ noble bees,’ said Ezra, ‘we offer ee our ’umble thanks for all your ’elp in drivin’ badness an’ sorrow away from our village. An’ I, old Ezra, in your presence, bless the day that brought these troublesome varmints to live at the Vicarage. Varmints they may be, but with your ’elp they’ve done a good work that won’t never be forgotten. Clothed in gold, they be, gold as yellow as your ’oney. Golden be their future an’ gold be in their ’earts for ever.’

The children, at this magnificent tribute, grew rosy and shyly ducked their heads and bobbed their

curtsies

once more, while behind the church the sky began to unroll the first bright banner of a sunset that was the most magnificent of any ever seen in those parts, a sunset that was spoken of for years to come.

Deep inside the hives the bees could be heard singing.

Uncle Ambrose arrived home very late that night, after spending a long time telling Lady Alicia that she had a son, and he went off very early the next morning and spent an even longer time telling Daft Davie that he had a mother. And then he took him to the Manor and left him there, with Lady Alicia and Moses and Abednego, and no one knew what happened within the Manor during the following week. All they knew was that Moses and Abednego were very busy in the overgrown shrubbery with hatchets and saws, the old driveway, and also that Moses went out shopping several times, looking very pleased with himself, and that on the second occasion he bought two dapple-grey horses.

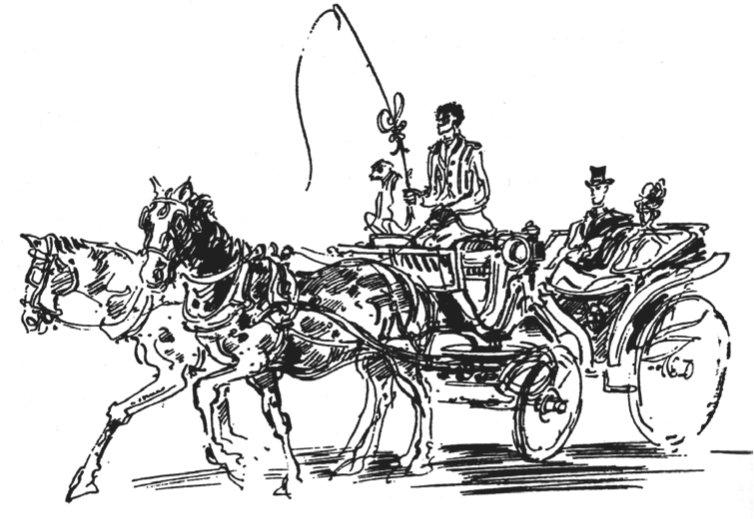

Then at the end of the week, the village had the surprise of its life, for Lady Alicia and her son Francis Valerian went out for a drive. It was the milkman, taking the morning’s milk to the Manor, who saw the ancient carriage, all polished and furbished up, issuing out of the stableyard with Moses and Abednego and Gertrude on the box. Moses and Abednego too were very much furbished up, and there was a large rosette of scarlet ribbon on the whip which Moses was brandishing over

the backs of the two dapple-grey horses. The milkman did not wait to see any more. He dumped the milk behind a bush and he ran as though for his life, though actually he was not afraid, he was merely running to rouse the village and bring it to its doors.

They were all at their doors when the gates were opened by Abednego and the Valerian carriage rolled through. It paused for a moment on the green to allow Abednego to jump back on his perch, and a great cheer went up from the villagers, and louder and louder cheers as more and more people came running up the hill to the green. Uncle Ambrose and Ezra and the children and Absolom came racing from the Vicarage; or rather the children and Absolom raced, while Uncle Ambrose and Ezra strode and stumped as fast as was compatible with adult dignity, and Hector flapped his wings and heated with joy on Uncle Ambrose’s broad shoulder.

Men came running from the fields and the women from their wash-tubs. The village school broke up in

confusion

and all the children came tumbling out. For only the older people in the village had ever seen Lady Alicia or her carriage, and though a few had seen the recluse who had lived in the Lion’s cave, they did not know what he would look like transformed into Francis Valerian.

He looked magnificent in a suit of fine cloth that had once belonged to his father, with his father’s cloak about his shoulders and his father’s tall hat on his head. His beard and his lion’s mane of hair had been trimmed and cut and he looked now a man in the prime of life. And Lady Alicia, in a beautiful lavender silk dress and a bonnet

trimmed with violets, looked no longer old, but merely elderly. She was smiling and happy and so was her son, and Moses and Abednego, very fine in their green velvet livery, were grinning from ear to ear. The old carriage, with the Valerian crest painted on the panels of the doors, shone almost as brightly in the sunshine as the coach of glass in which Cinderella drove to the ball.

With cheering people lining the way they drove down the hill past the Vicarage and then over the bridge and up the hill beyond. The people did not follow up the hill, for they thought that Lady Alicia would want to be alone with her son and her faithful servants, when, after so many years, she saw the moors again. So the strange old carriage rolled away unattended to where the larks were singing in a cloudless blue sky, and the wind was warm and honey-scented and the bees were humming in the gorse. They were gone for quite a long time and when they came back they looked happier than ever.

The people did not cheer this time, for too much cheering can be trying for the people who are cheered,

but when they heard the carriage wheels they came to the doors and waved and smiled. And Tom Biddle stood at his door and waved and smiled, and Emma Cobley stood at her door and curtsied and smiled, with Frederick beside her, and as the carriage passed the shop Lady Alicia turned and smiled at Emma and because she was so happy, and wanted everyone else to be happy, she forgave Emma all her wickedness from the bottom of her heart. Yet as she drove back through the shrubbery to the Manor she was weeping a little, because in the last few days all her old love for her husband had come back again and she was very sorry indeed that he had lost himself.

The only people who were not at their doors to smile at Lady Alicia were Eliza and William Lawson. They were not there because they had gone away. William was not a Devonian, he had never been happy at High Barton; he thought it rained a lot in the west country and he thought they would be happier somewhere else. So they went and they were not missed, and the village settled down to enjoy the finest summer anyone could remember, with no more rain than was necessary for the gardens and the crops.

But Emma and Tom did not go away and they became quite nice old people. Their change of heart was

astonishing

at their age and the villagers were at a loss to explain it. Of course they did not know what a hard fight the goodwill of the children and Uncle Ambrose and Ezra had put up against the ill will that had opposed them, and they did not know about Ezra’s good spells or the labour

of the bees. Least of all did they know how Lady Alicia had forgiven Emma from the bottom of her heart.

It was a wonderful summer, with one happy thing after the other falling into place like pearls threaded on a string. The children worked hard at their lessons, spurred on with the promise of a month’s whole holiday in September if they deserved it, but they had fun too. They spent a lot of time with Lady Alicia and her son. Nan and Betsy helped Lady Alicia sweep away cobwebs and make new cushions and curtains for the Manor house, and Robert and Timothy helped Francis weed the garden, and day by day, as house and garden came slowly back to their old order and beauty, Lady Alicia and her son grew younger and younger and happier and happier. And so did Moses and Abednego.

But Francis still kept his home in the Lion Rock. He had it as his workshop and did carpentry there and painted beautiful pictures on canvas with oil-paints. He had always wanted to do this, but had never had enough money to buy the paints. Of course he was not really daft, and he never had been, he had only been called daft by the country people, because in his efforts to speak he had made queer noises. He was really a very clever man as well as a very good and charming one. All the children loved him, but especially Nan. She often went with him to his workshop and read aloud to him while he painted. Neither of them had ever been so happy as they were when they read and painted together. At these times Nan felt she would have nothing left to wish for if only her father were here. And Francis felt very much the same. If only, he thought, the father whom he remembered so

vividly had not been so foolish as to lose himself. If only he were here too, how perfect life would be.

Robert also was happy and content because he had at last saved up enough money to buy a proper bridle for Rob-Roy and gallops on the moor became more wonderful than ever. Sometimes Moses and Abednego came too, riding the two dapple-grey horses. They made an astonishing trio of riders, and strangers driving over the moor and seeing them could hardly believe their eyes. Sometimes they stopped their carriages and gazed with their mouths open, and then Robert, Moses, and Abednego would wave their hands in greeting and shake their reins and canter away laughing.

It was on a day in August, when the moor was purple with heather and the bracken was just beginning to turn gold, that a cab with two men inside and luggage on the roof came bowling across the moor and came in sight of the three riders. One of the two men inside called out to the driver and the cab stopped. The driver gazed in stupefaction, but the two men jumped out of the cab and came striding towards the riders. They were tall men, much of a height, their faces tanned golden brown, and one of them had a fine lion-like head and grey hair and a grey beard.

‘Moses!’ cried out a voice. ‘Abednego!’

And the other man, who was fair with a fair

moustache

, called out, ‘Robert!’

Then followed one of those times that are afterwards remembered as though they had happened in a dream, or in heaven, or on another star, because they seem too wonderful to belong to earth. Moses, Abednego, and

Robert fell off their mounts and ran to meet the two men, who seemed as they strode over the heather to be gods, not men, so strong and tall were they, so golden, gay, laughing, and splendid in the sun. But Moses, Abednego, and Robert, though their hearts were nearly bursting with joy, could not laugh. Moses, as he ran across the heather and fell on his knees before the lion-man, was sobbing, and Robert, springing into his father’s arms, was crying too. Abednego, having leapt to the lion-man’s shoulder, wiped his eyes on Gertrude. It was as though for the first time in their lives they saw the sun burst out from behind a cloud. The two horses and Rob-Roy watched for a few minutes and then, coming slowly nearer, whinnied and gently thrust their muzzles against the necks and chests of the men and boy and monkey. They did not altogether understand what was happening, but they knew it was an occasion that called for the unobtrusive steadying influence of their

marvellous

equine sympathy. The horse who was drawing the cab whinnied too and the driver thrust his bowler hat to the back of his head and stared and stared.

A little later the sound of wheels once more brought the village to its doors to watch another carriage

procession

, as the three riders triumphantly led the cab over the bridge and up the hill to the Vicarage. The villagers were puzzled, but they laughed and waved because the faces of Moses, Abednego, and Robert told them that this was a matter for joy. At the Vicarage door Robert, Rob-Roy, and some of the luggage and one of the two god-like men were separated from the main cavalcade, and then as the cab went on up the hill to the green,

with Moses riding in front and Abednego behind, and the remaining god-like man leaning forward and waving to them from inside the cab, the emotion in his face and his likeness to his son told them who he was. When they saw the cab drive in through the Manor house gates they began to cheer wildly. The last squire was not dead after all. The squire was home.

He was the man who had lost his memory, whom the children’s father, Colonel Linnet, had met in Egypt, and his memory had returned to him when Ezra had taken the pins out of the head and feet of the figure of the tall man. He was delighted to be home and Lady Alicia and Francis were delighted to have him home. It was, of course, a great shock to Lady Alicia to have her lost husband restored to her so suddenly, and so soon after the restoration of her son, but she had longed for him and she was a strong elderly lady, and the air of the high moors is invigorating, and so she not only survived but became younger and happier than ever.

They did the same at the Vicarage, for Colonel Linnet had applied for special leave to bring Hugo Valerian back to his home, and in the very peculiar and special circumstances it had been granted him and he could stay for three weeks. The first fortnight of the three weeks was wonderful, but during the last week a certain gloom made itself felt, for even though they had Uncle Ambrose and Ezra, the children felt they could not bear the coming parting. And their father felt the same. And so did Uncle Ambrose and Ezra and all the animals. The gloom grew steadily worse until

suddenly one day at lunch Colonel Linnet said to Uncle Ambrose, ‘I wish to heaven I could leave the army, live here with you and the children and take up farming.’