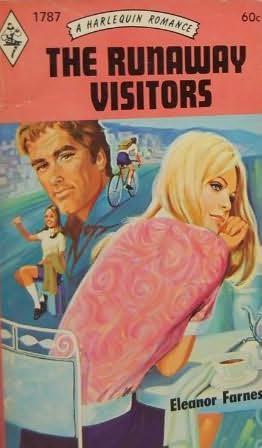

The Runaway Visitors

Read The Runaway Visitors Online

Authors: Eleanor Farnes

The Runaway Visitors

ELEANOR FARNES

Victoria thought she could look after her young brother and sister while her parents were abroad. They decided otherwise.

So Victoria found herself in Italy, entrusted to the care of the disagreeable Charles Duncan, who was anything but pleased at having these juveniles thrust upon him.

CHAPTER I

‘According to this letter,’ Victoria said, lifting her head to look at her brother and sister seated at the breakfast table with her, ‘we’re to be shipped off to Italy for the summer. ’

‘Italy?’ said Amanda, astonished. ‘Whatever for?’

‘Italy?’ Sebastien was even more unconvinced. ‘I thought we were going to Aunt Catherine in Norfolk.’

‘According to Mother,’ went on Victoria, ‘Aunt Catherine can’t have us. She’s having friends to stay with her, on and off, so won’t have enough bedrooms; and she’s having a very busy summer and won’t have enough time for us.’

‘In other words,’ said Sebastien, almost too drily for a sixteen-year-old, ‘Aunt Catherine doesn’t want us.’ They all looked at each other with a kind of unhappy resignation. They were always being shipped off to somebody or other, and had been for as long as they could remember.

‘I see absolutely no reason why we couldn’t stay here all together,’ said Victoria. ‘I’m nearly twenty and I keep house much more efficiently than Mother, even when she

is

here. She seems to think the responsibility of looking after a family is too much for me; so off we have to go to Italy.’

‘Before the end of term?’ asked Sebastien.

‘Yes. She says it’s all arranged. Your exams are finished and she doesn’t think the rest of term is important.’

‘What about my exams?’ put in Amanda.

‘She doesn’t seem to think they’re important either.’

‘And I was going to camp from Aunt Catherine’s,’ said Sebastien. Victoria shrugged her shoulders. It was impossible to argue with parents who were on their way to New Guinea, impossible to contest the arrangements for air tickets and finance.

‘And how do we know that these people in Italy don’t want us either?’ asked Sebastien after a troubled pause.

‘It isn’t people. It’s a person. A man, a sculptor called Charles Duncan. He’s got a rambling old Etruscan farmhouse in the hills

above Florence.’

‘Oh, this Charles we’re always hearing about?’ asked Amanda. ‘That one, yes. He's been a great friend of Mother and Dad ever since they bought one of his very first exhibited sculptures.’

‘Do you know him?’ asked Sebastien.

‘I remember him. I wouldn’t say I

know

him. I think I was nine when I last saw him, and since then he’s become quite famous. Mother and Dad have seen him lots of times: in Florence and New York and here in London, but always going out to dinner with him or in friends’ houses. I don’t know what he’s like now. ’

‘Well, what makes Mother think a

man

can look after us, if you can’t?’ asked Sebastien.

‘Apparently, still according to Mother’s letter, he once said to her when she was wondering what to do with us, that she could always send us to him, he’d be delighted to have us. And he’s got a Scottish housekeeper, apparently.’

‘She’ll

love

having three strangers dumped on her.’ Victoria folded the letter and replaced it in its envelope. She sensed the let-down and disappointment in Sebastien and thirteen-year-old Amanda, and she smiled at them both encouragingly. ‘Oh, you never know,’ she said with an attempt at cheerfulness. ‘She might be a very nice person, and Charles Duncan will probably be too busy to take much notice of us; and I can always help the Scottish housekeeper, to keep her sweet. It may not turn out too badly.’

When Sebastien and Amanda had gone off to school, however, Victoria was not quite so cheerful. She cleared away the breakfast dishes and washed them in the light, airy, newly-decorated kitchen, looking out over the narrow London garden she tended so carefully, thinking that it would all go to pot while she was wasting her time in Italy. Sebastien had said, putting books into a briefcase, slinging another bag over his shoulder: ‘I don’t know why they don’t stay home and look after their own children, like other boys’ parents,’ and sometimes Victoria too envied the young people who had their parents always with them, envied the warmth and security they must feel.

It was all very well to have such wonderful, interesting, talented parents, but should they want to have their cake and eat it too?

Should they

have

a family if they didn’t have the time to devote to it? Friends were always saying to Victoria, Sebastien and Amanda: ‘We saw your parents on television last night—they were awfully interesting.’ Or: ‘Your mother looked so beautiful, you can’t imagine her grubbing about in all those jungles and things for new plants.’ For their mother was a botanist, well-known among her colleagues at first, later well-known because of television which made her familiar to hundreds of thousands. She would appear, beautiful, elegant, charming—not at all like a blue-stocking—after each of her expeditions: to the Amazonian jungle or to the mountains of Nepal or some other exotic spot.

And it wasn’t only Mother, for their father was now a big name among the conservationists, and as this was also a subject often aired ‘on the box’, he had his innings, too. He had been a mining engineer. All over the world, just like Mother. He had made quite a fortune, in a complicated way to do with mining shares which Victoria did not understand. And then, later, he had become seriously concerned about the destruction of the environment and had turned his considerable intellect to the problem of conserving it. So he sat on committees, and he went off to study the problem in the field, and now he was on his way to New Guinea to one of the largest copper mines in the world; and Mother was with him, not to look at mines but to look for plants; and once more, Victoria, Sebastien and Amanda would be ‘shipped off ’.

Victoria thought it was not so much that they didn’t realise she had grown up, as that they didn’t

want

to realise it. They wanted to keep the three together, wanted to know that Victoria was there to keep an eye on the other two. Not that Sebastien needed it. He was already fairly self-sufficient. In fact, there was often a dryness about his comments that bordered on cynicism, and Victoria wondered sometimes if he was losing his precious youthfulness by developing a hard shell around him. Perhaps he had been hurt by his parents’ frequent departures (which nobody ever thought of calling neglect) and was determined that life was not going to have the power to hurt him.

Amanda needed a protective eye much more. She was a temperamental thirteen-year-old, and that was an awkward age enough without an added dose of temperament. She cried easily. She got depressed. Victoria was her prop and stay; and Victoria knew that, for Amanda’s sake alone, she would go off to Charles Duncan’s Etruscan farm for the summer, and put up with whatever awaited her.

For there had been all kinds of awkwardnesses and embarrassments in the various places that had welcomed them at first and then got bored by them, or resented the length of the visit, or the extra work. Victoria had had to keep the peace, or make herself useful, or try in one way or another to atone for the inconvenience they caused.

‘For two pins,’ she said to the neighbour’s ginger cat exploring her herbaceous border, ‘ I wouldn’t go to Italy. I’d stay home and run the house here and Sebastien could go to camp and Amanda could go on with her ballet classes. It’s quite unnecessary for Mother to make

any

arrangements for us.’ Although she knew that these arrangements, in some strange way, alleviated her mother’s pangs of conscience. Mother would think—and say: ‘The darlings are having a wonderful summer in Italy.’ Even if the darlings felt unwanted and in the way and would rather be in their familiar surroundings in dear old London.

When Sebastien and Amanda returned at the end of the afternoon the three of them had another consultation over tea. Both Sebastien and Amanda were more cheerful, since their news had aroused interest and envy among their schoolfellows, and even interest from masters and mistresses at the news that they were visiting so eminent a sculptor as Charles Duncan.

‘Well, I’ve been thinking too,’ said Victoria. ‘I think we’ve got to have some measure of independence. We don’t know where this farm is—it might be miles from anywhere, away in the hills. You remember the Inneses’ house in Scotland—four miles from the village, the car never available, hiring those old bikes to toil up all those hills? Well, I’m not having any more of that. We won’t go by air. We’ll go by car, and then we’ll have it with us to get about in. And it will be cheaper—we’ll have extra spare money.’

So she set about the formalities. Their passports were always in order. She booked the passage on the car ferry and wrote to Charles Duncan to give him an approximate date of their arrival. She had to select the clothes they would need to take, and wash them or see they were dry-cleaned; and ask their neighbour to keep an eye on the house; and turn off the boiler and leave messages for the tradesmen and do the many things any responsible housewife has to do; and pack up the car, taking the picnic gear and the dozens of things Sebastien and Amanda decided they could not do without. And yet Mother still thought arrangements had to be made for them!

The day came when they boarded the car ferry at Dover, and inevitably a feeling of adventure came with it. The queueing to go on board, the glitter on the sea, the receding white cliffs of Dover, the sudden clatter of the strange French tongue, driving on the right along the straight French roads, finding little inns to spend the nights in, or lovely spots for picnic lunches. Over the Alps and into Italy and along the motorways there: no dallying nowadays in the lovely, historic, mediaeval villages, but straight through on the autoroute to the sun!

Behind the interest of the journey, however, behind the colourful places they stayed in and passed through, they were aware of a faint anxiety that grew stronger as they approached their destination. Victoria, especially, upon whom the brunt of the visit usually fell. What was Charles Duncan like now? What sort of woman was his housekeeper?

Charles Duncan she remembered as a tall man and broad, with large strong hands and a shock of brown hair. He had come to their house several times when she was about nine years old, and he had had little time for the three children then, aged nine, six and three. Victoria remembered that he had said to her: ‘ What, is there another beauty in the family? Are you going to be as beautiful as your mother?’ For that was really the first time she had seen her mother as beautiful in the world’s eyes. Perhaps she remembered him as tall simply because she herself had been small then? Perhaps the brown hair was grey now? She thought he was younger than her parents, but realised that she had always thought of him as their friend and had not been particularly interested in him. Now she had to be.

The housekeeper, too. She could make their life pleasant, or distinctly unpleasant, she could make them feel unceasingly a burden. Victoria worried about it as they drove into Florence; and the others, sensing her anxiety, became quiet too.

‘Read the instructions to me, Sebastien,’ she said. ‘We take the

Fiesole road, don’t we?’

He began to read the instructions which Charles Duncan had sent to them. Yes, it was the Fiesole road, climbing and winding its way out of Florence, the scent of the lime trees in flower finding its way into the car. And at a certain point they turned off to the right along a rough, metalled road from which various private drives led away; and then over a rougher, country road for some distance that led them to a rambling old building of considerable size, constructed of the mellow golden stone of the area, touched by terra-cotta. Victoria stopped the car, so that they could take a good look at it.

‘Well, we’re here,’ she said.

‘Is that it?’ asked Amanda.

‘Undoubtedly. It answers the descriptions.’

‘It looks awfully crumbling and old.’

‘It looks absolutely beautiful,’ said Victoria.

To her eyes, it did. Hundreds of years old, she thought. A complex of house and farm buildings, and a lovely small tower at one end that could only be in Tuscany. A real old Italian farm, she thought, with a lift of the heart. Sitting there under the warmth of the sun as it had for centuries. Considerably cheered, she re-started the engine, drove through the gateway and along a well-constructed driveway, and stopped at the entrance to the house.