The Rule of Four (35 page)

On the way to Firestone we pass Carrie Shaw, a junior I recognize from an English class last year, who crosses in front of us and says hi. She and I traded glances across the seminar table for weeks before I met Katie. I wonder how much has changed for her since then. I wonder if she can see how much has changed for me.

“It seems like such an accident that I got sucked into the

Hypnerotomachia

,” Paul says as we continue heading east toward the library. “Everything was so indirect, so coincidental. The same way it was for your dad.”

“Meeting McBee, you mean.”

“And Richard. What if they’d never known each other? What if they’d never taken that class together? What if I’d never picked up your dad’s book?”

“We wouldn’t be standing here.”

He takes it as a throwaway at first, then realizes what I mean. Without Curry and McBee and

The Belladonna Document,

Paul and I would never have met. We would’ve crossed paths on campus the same way Carrie and I just did, saying hello, wondering where we’d seen each other before, thinking in a distant way what a shame it was that four years had passed and there were still so many unfamiliar faces.

“Sometimes,” he says, “I ask myself, why did I have to meet Vincent? Why did I have to meet Bill? Why do I always have to take the long way to get where I’m going?”

“What do you mean?”

“Did you notice how the portmaster’s directions don’t get straight to the point, either? Four south, ten east, two north, six west. They move in a big circle. You almost end up where you started.”

Finally I understand the connection: the wide sweep of circumstance, the way his journey with the

Hypnerotomachia

has wound through time and place, from two friends at Princeton in my father’s day, to three men in New York, to a father and son in Italy, and back now to another two friends at Princeton—it all resembles Colonna’s strange riddle, the directions that curl back on themselves.

“Don’t you think it makes sense that your father is the one that got me started on the

Hypnerotomachia

?” Paul asks.

We arrive at the entrance, and Paul opens the library door for me, as we duck in from the snow. We are in the old heart of campus now, a place made of stones. On summer days, when cars streak by with their windows down and their radios up, and the whole student body wears shorts and T-shirts, buildings like Firestone and the chapel and Nassau Hall seem like caves in a metropolis. But when the temperature drops and the snow falls, no place is more reassuring.

“Last night I started thinking,” Paul continues, “Francesco’s friends helped him design the riddles, right? Now our friends are helping to

solve

them. You figured out the first one. Katie answered the second one. Charlie knew the last one. Your dad discovered

The Belladonna Document

. Richard found the diary.”

We pause at the turnstile, flashing our campus IDs to the guards at the gate. As we wait for the elevator to C-floor, all the way at the bottom, Paul points to a metal plate on the elevator door. There’s a symbol engraved on it that I’ve never noticed before.

“The Aldine Press,” I say, recognizing it from my father’s old office at home.

Colonna’s printer, Aldus Manutius, took his famous dolphin and anchor emblem, one of the most famous in printing history, from the

Hypnerotomachia.

Paul nods, and I sense this is part of his point. Everywhere he’s turned, in this four-year spiral back toward the beginning, he’s felt a hand at his back. His whole world, even in the silent details, has been nudging him on, helping him to crack Colonna’s book.

The elevator doors open, and we step in.

“Anyway, I was thinking about all that last night,” he says, pressing the button for C-floor as we begin our descent. “About how everything seemed to be coming full circle. And it hit me.”

A bell dings above our heads, and the doors open onto the bleakest landscape of the library, dozens of feet underground. The ceiling-high bookshelves of C-floor are so tightly packed that they seem designed to shoulder the weight of the five floors above us. To our left is Microform Services, the dark grotto where professors and grad students huddle in clusters of microfilm machines, squinting at panels of light. Paul begins leading me through the stacks, running his finger along the dusty spines of books as we pass them. I realize he’s taking me to his carrel.

“There’s a reason everything returns to where it started in this book. Beginnings are the key to the

Hypnerotomachia

. The first letter of every chapter creates the acrostic about Fra Francesco Colonna. The first letters of the architectural terms spell out the first riddle. It’s not a coincidence that Francesco made everything come back to beginnings.”

In the distance I can see the long rows of green metallic doors, spaced almost as closely as high school lockers. The rooms they guard are no bigger than closets. But hundreds of seniors shut themselves inside for weeks on end to write their theses in peace. Paul’s carrel, which I haven’t seen in months, sits near the farthest corner.

“Maybe I was just getting tired, but I thought, what if he knew exactly what he was doing? What if you could figure out how to decipher the second half of the book by focusing on something in the very first riddle? Francesco said he didn’t leave any solutions, but he didn’t say he left no hints. And I had the directions from the portmaster’s diary to help me.”

We arrive in front of his carrel, and he begins to twist the combination lock on the door. A sheet of black construction paper has been taped to the little rectangular window, making it impossible to see inside.

“I thought the directions had to be about a physical location. How to get from a stadium to a crypt, measured in stadia. Even the portmaster thought the directions were geographical.” He shakes his head. “I wasn’t thinking like Francesco.”

Paul opens the lock and swings the door wide. The little room is filled with books, piles upon piles of them, a tiny version of the President’s Room at Ivy. Food wrappers litter the floor. Sheets of paper are taped to the walls, thick as feathers, each one scrawled with a message.

Phineus son of Belus wasn’t Phineus king of Salmydessus,

says one.

Check Hesiod: Hesperethousa or Hesperia and Arethousa?

says another.

Buy more crackers,

says a third.

I lift a stack of photocopies from one of the two chairs crammed into the carrel, and try to sit down without knocking anything over.

“So I came back to the riddles,” he says. “What was the first riddle about?”

“Moses. The Latin word for horns.”

“Right.” He turns his back to me to shut the door behind us. “It was about a mistranslation. Philology, historical linguistics. It was about

language

.”

He begins searching through a column of books atop the hutch of his desk. Finally he finds what he wants: Hartt’s

History of Renaissance Art.

“Why did we get lucky with the first riddle?” he says.

“Because I had that dream.”

“No,” he says, finding the page with Michelangelo’s sculpture of Moses, the picture that began our partnership. “We got lucky because the riddle was about something verbal, and we were looking for something physical. Francesco didn’t care about actual, physical horns; he cared about a word, a mistranslation. We got lucky because that mistranslation eventually manifested itself physically. Michelangelo carved his Moses with horns, and you remembered that. If it hadn’t been for the physical manifestation, we would never have found the linguistic answer. But that was the key: the

words

.”

“So you looked for a linguistic representation of the directions.”

“Exactly. North, south, east, and west aren’t

physical

clues. They’re

verbal

ones. When I looked at the second half of the book, I knew I was right. The word

stadia

shows up near the beginning of the very first chapter. Look,” he says, finding a sheet of paper where he’s worked something out.

There are three sentences written on the page:

Gil and Charlie go to the stadium to watch Princeton vs. Harvard. Tom waits as Paul catches up. Katie takes photographs while winsomely smiling and mouthing, I love you, Tom.

“Winsomely?” I say.

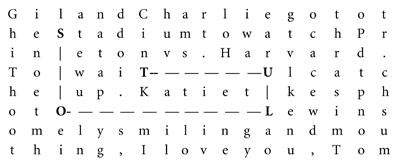

“Doesn’t look like much, right? It just sort of rambles, like Poliphilo’s story. But plot it out in a grid,” he says, turning the piece of paper over. “And you get this:”

I’m waiting for something to jump out at me, but it doesn’t.

“That’s it?” I ask.

“That’s it. Just follow the directions. Four south, ten east, two north, six west.

De Stadio

—‘from stadium.’ Start with the ‘s’ in ‘stadium.’ ”

I find a pen on his desk and try it out, moving down four, right ten, up two, and left six.

I write down the letters S-O-L-U-T.

“Then repeat the process,” he says, “starting with the last letter.”

I begin again from T.

And there it is, laid out on the page: S-O-L-U-T-I-O-N.

“

That’s

the Rule of Four,” Paul says. “It’s so simple once you understand how Colonna’s mind works. Four directions

within

the text. Just repeat it over and over again, then figure out where the word breaks are.”

“But it must’ve taken Colonna months to write.”

He nods. “The funny thing is, I’d always noticed there were certain lines in the

Hypnerotomachia

that seemed even more disorganized than others—places where words didn’t really fit, where clauses were in strange places, where the weirdest neologisms turned up. It makes sense now. Francesco had to write the text to fit the pattern. It explains why he used so many languages. If the vernacular word didn’t fit in the spaces, he would have to try the Latin word, or make one up himself. He even made a bad choice with the pattern. Look.”

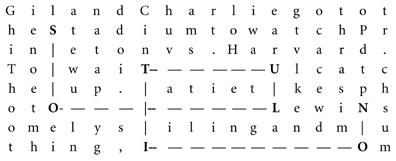

Paul points to the line where O, L, and N appear.

“See how many cipher letters are on that one line? And there’ll be another one once you go six west again. The four-south, two-north pattern doubles back on itself, so every other line in the

Hypnerotomachia,

Francesco had to find text that fit four different letters. But it worked. No one in five hundred years picked up on it.”

“But the letters in the book aren’t printed that way,” I say, wondering how he applied the technique to the actual text. “Letters aren’t spaced evenly in a grid. How do you figure out what’s exactly north or south?”

He nods. “You can’t, because it’s hard to say which letter is directly above or below another. I had to work it out mathematically instead of graphically.”

It still amazes me, the way he teases simplicity and complexity out of the same idea.

“Take what I wrote, for example. In this case there are”—he counts something—“eighteen letters per line, right? If you work it out, that means ‘four south’ will always be four lines straight down, which is the same as seventy-two letters to the right of the original starting point. Using the same math, ‘two north’ will be the same as thirty-six letters to the left. Once you know the length of Francesco’s standard line, you can just figure out the math and do everything that way. After a while, you get pretty quick at counting the letters.”