The Rule of Four (23 page)

“These are the directions. They’re in Latin. They say:

Four south, ten east, two north, six west.

Then they say

De Stadio.”

“What’s

De Stadio

?”

Paul smiles. “I think that’s the key. The portmaster took it to his cousin, who told him

De Stadio

was the scale that went with the directions. It can be translated ‘Of Stadia,’ meaning the directions are measured in stadia.”

“I don’t get it.”

“The stadium is a unit of measurement from the ancient world, based on the length of a footrace in the Greek Olympics. That’s where we get our modern word. About six hundred feet is one stadium, so there are between eight and ten stadia in a mile.”

“So

four south

means four stadia south.”

“Then ten east, two north, and six west. It’s all four directions. Does it remind you of something?”

It does: in his final riddle, Colonna referred to what he called a Rule of Four, a device that would lead readers to his secret crypt. But we gave up on finding it when the text itself failed to produce anything remotely geographical.

“You think that’s it? Those four directions?”

Paul nods. “But the portmaster was looking for something on a much bigger scale, a voyage of hundreds and hundreds of miles. If Francesco’s directions are in stadia, then the ship couldn’t have originated in France or the Netherlands. It must’ve started its trip about half a mile southeast of Genoa. The portmaster knew that couldn’t be right.”

I can see Paul’s giddiness, thinking he’s done the portmaster one better. “You’re saying the directions were meant for something else.”

He hardly pauses. “

De Stadio

doesn’t just have to mean ‘Of Stadia.’

De

could also mean ‘from.’ ”

He looks at me expectantly, but the beauty of this new translation is lost on me.

“Maybe the measurements aren’t just

of

stadia, or measured in those units,” he says. “Maybe they’re also taken

from

a stadium. A stadium could be the starting point.

De Stadio

could have a double meaning—you follow the directions

from

a physical stadium building,

in

stadia units.”

The map of Rome projected on the wall is coming into focus. The city is littered with ancient arenas. Colonna would’ve known it better than any city in the world.

“It solves the scale problem the portmaster had,” Paul continues. “You can’t measure the distance between countries in a few stadia. But you

can

measure the distance across a city that way. Pliny says the circumference of the Roman city walls in

A.D.

75 was about thirteen miles. The entire city was maybe twenty-five or thirty stadia across.”

“You think that will lead us to the crypt?” I ask.

“Francesco talks about building where no one can see. He doesn’t want anyone to know what’s inside it. This may be the only way to find the location.”

Months of speculation return to me. We spent many nights wondering why Colonna would build his crypt out in the Roman forests, hidden from his family and friends, but Paul and I never agreed about our conclusions.

“What if the crypt is more than we thought?” he says. “What if the location

is

the secret?”

“Then what’s inside it?” I say, reviving the question.

Paul’s demeanor changes to frustration. “I don’t know, Tom. I still haven’t figured it out.”

“I’m just saying, don’t you think Colonna would’ve—”

“Told us what was in the crypt? Of course. But the entire second half of the book depends on the last cipher, and I can’t solve it. Not alone. So this diary is it. Okay?”

I back off.

“So all we have to do,” Paul goes on, “is look at a few of these maps. We start at the major stadium areas—the Coliseum, the Circus Maximus, and so on—and move four stadia south, ten east, two north, and six west. If any of those locations is in what would’ve been a forest in Colonna’s time, we mark it.”

“Let’s look,” I say.

Paul presses the Advance button, shifting through a series of maps made in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. They have the quality of architectural caricatures, buildings drawn out of proportion with their surroundings, crowded up against each other until the spaces in between are impossible to judge.

“How are we going to measure distances on those?” I ask.

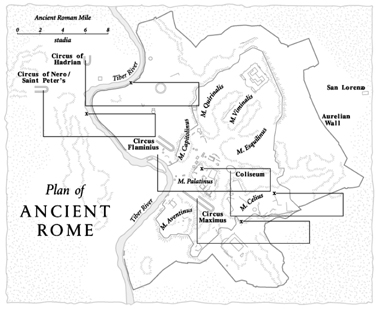

He answers me by pumping the hand control several more times. After three or four more Renaissance maps, a modern one appears. The city looks more like the one I remember from travel books my father gave me before our trip to the Vatican. The Aurelian Wall on the north, east, and south and the Tiber River on the west create the profile of an old woman’s head facing the rest of Italy. The church of San Lorenzo, where Colonna had the two men killed, hovers like a fly just beyond the arch of the old woman’s nose.

“This one has the right scale on it,” Paul says, pointing to the measurements in the upper-left corner. Eight stadia are marked along a single line, labeled

ANCIENT ROMAN MILE.

He walks toward the image on the wall and places his hand beside the scale. From the base of his palm to the tip of his middle finger, he covers the full eight stadia.

“Let’s start with the Coliseum.” He kneels on the floor and places his hand near a dark oval in the middle of the map, near the old woman’s cheek. “Four south,” he says, moving a palm-length down, “and ten east.” He moves one full hand-length across, then adds half an index finger. “Then two north and six west.”

When he finishes, he’s pointing to a spot labeled

M

.

CELIUS

on the map.

“You think that’s where it is?”

“Not there,” he says, deflated. Pointing to a dark circle on the map just southwest of his finishing point, he says, “Right over here is a church. San Stefano Rotondo.” He shifts his finger northeast. “This is another one, Santi Quattro Coronati. And here”—he moves the finger southeast—“is Saint John Lateran, where the popes lived until the fourteenth century. If Francesco had built his crypt here, he would’ve done it within a quarter mile of three different churches. No way.”

He begins again. “The Circus Flaminius,” he says. “This map is old. I think Gatti placed it closer to here.” He moves his finger closer to the river, then repeats the directions.

“Good or bad?” I say, staring at the location, somewhere atop the Palatine Hill.

He frowns. “Bad. This is almost right in the middle of San Teodoro.”

“Another church?”

He nods.

“You’re sure Colonna wouldn’t have built it near a church?”

He looks at me as if I’ve forgotten the cardinal rule. “Every message says he’s terrified of being caught by the zealots. The ‘men of God.’ How do

you

interpret that?”

Losing patience, he tries two other possibilities—the Circus of Hadrian and the old Circus of Nero, over which the Vatican was built—but in both cases, the rectangle of twenty-two stadia lands him almost in the middle of the Tiber River.

“There’s a stadium in every corner of this map,” I tell him. “Why don’t we think about where the crypt could be, then work backward to see if there’s a stadium near it?”

He mulls it over. “I’d have to check some of my other atlases at Ivy.”

“We can come back here tomorrow.”

Paul, whose supply of optimism is thinning, eyes the map a moment longer, then nods. Colonna has beat him again. Even the spying portmaster was outwitted.

“What now?” I ask.

He buttons his coat, turning off the projector. “I want to check Bill’s desk in the library downstairs.” He returns the slide machine to its shelf, trying to leave everything where he found it.

“Why?”

“To see if anything else from the diary is there. Richard insists there was a blueprint folded inside it.”

He opens the door and holds it for me, checking the room before locking it up.

“You have a key for the library?”

He shakes his head. “Bill told me the punch code for the stairwell.”

We return into the darkness of the hallway, where Paul leads me down the corridor. Orange security lights wink in the darkness like airplanes crossing at night. We come to a door leading to a stairwell. Below the knob is a box with five numbered buttons. Paul thinks for a second, then begins to punch a short sequence. As the knob unlocks in his hand, both of us freeze. In the silence we can hear something shuffling.

Chapter 14

Go,

I mouth, nudging Paul toward the library door.

A plate of security glass forms a small window in the panel, and we peek through it into the darkness of the room.

A shadow is shifting across the top of one of the private tables. The beam of a flashlight hovers across its surface. I can make out a hand reaching into one of the drawers.

“That’s Bill’s desk,”

Paul whispers.

His voice carries in the stairwell. The path of the flashlight freezes, then moves in our direction.

I push Paul down below the window.

“Who is that?”

I ask.

“I couldn’t see.”

We wait, listening for footsteps. When we hear them moving away into the distance, I peek into the room again. It’s empty.

Paul pushes the door forward. The entire area is sunk in the long shadows of bookshelves. Moonlight presses at the sheet-glass windows to the north. The drawers of Stein’s desk are still open.

“Is there another exit?”

I whisper as we approach.

Paul nods and points past a series of ceiling-high shelves.

Suddenly there are footsteps again, shuffling in the direction of the exit, followed by a click. The door latches gently into place.

I move toward the sound.

“What are you doing?” Paul whispers. He signals me back to him, by the desk.

I peer out the security glass into the far stairwell, but I can make out nothing.

Paul is already rummaging through Stein’s papers, splaying his penlight over a clutter of notes and letters. He points at a locked drawer that’s been pried open. The files in it have been pulled out and scattered over the desk. Edges of paper curl up like untended grass. There seems to be a folder for every professor in the history department.

RECOMMENDATION: CHAIRMAN WORTHINGTON

REC (A-M): BAUM, CARTER, GODFREY, LI

REC (N-Z): NEWMAN, ROSSINI, SACKLER, WORTHINGTON

(PRE-CHAIR)

REC (OTHER DEPTS): CONNER, DELFOSSE, LUTKE, MASON,

QUINN

OLD CORRESPONDENCE: HARGRAVE/WILLIAMS, OXFORD

OLD CORRESPONDENCE: APPLETON, HARVARD

It means nothing to me, but Paul is fixed on them.

“What’s wrong?” I ask.

Paul runs his flashlight across the desktop. “Why does he need all these recommendations?”

Two other files lie open. One is titled

REC/CORRESPONDENCE: TAFT.

The other is

LEVERAGE/LEADS.

Taft’s letter has been pushed into a corner, brushed aside. Paul rolls his shirt cuff over his fingers and yanks the paper into view.

William Stein is a competent young man. He has worked under me for five years, and has mainly been useful in matters administrative and clerical. I am confident that he will do a similar job wherever he goes.

“God,” Paul whispers. “Vincent screwed him.” He reads it again. “Bill sounds like a secretary.”

When Paul unfolds the dog-eared corner of the page, the date is from last month. He picks it up, revealing a handwritten postscript.

Bill: I am writing this for you in spite of everything. You deserve less. Vincent.

“You bastard . . .” Paul whispers. “Bill was trying to get away from you.”

He pans the flashlight over the

LEVERAGE/LEADS

folder. A series of Stein’s letter drafts lies on top, worked over in several pens. Lines have been inserted and removed until the text is difficult to follow. As Paul reads them, I can see the penlight begin to quiver in his hand.

Don Hargrave,

begins the first letter,

I am pleased to inform you that my research on the

Hypnerotomachia Poliphiliis completenears completion. My results will be available by the end of April, if not sooner. I assure you they are worth the wait. As I have heard nothing from you and Master Williams since my letter of 17 January, please confirm that theprofessorshipposition we discussed remains available. My heart is with Oxford, but I may not be able to fend off other universities once my paper is published and I’m faced with new offers.

Paul flips to the following page. I can hear him breathing now.

Chairman Appleton, I write to you with good news. My work on the

Hypnerotomachia

draws successfully to a close.As promised,The results will cast a shadow over everything else in Renaissance historical studies—or any historical studies—this year or next. Before I publish my results, I want to confirm that the assistant professorship is still available. My heart is with Harvard, but I may not be able to fend off other temptations once my paper is published and I’m faced with new offers.