The Rosetta Key

Authors: William Dietrich

Tags: #Americans - Egypt, #Historical, #Action & Adventure, #Egypt, #Gage; Ethan (Fictitious character), #Egypt - History - French occupation; 1798-1801, #Egypt - Antiquities, #Fiction, #Americans, #Historical Fiction, #Relics, #Suspense

Synopsis:

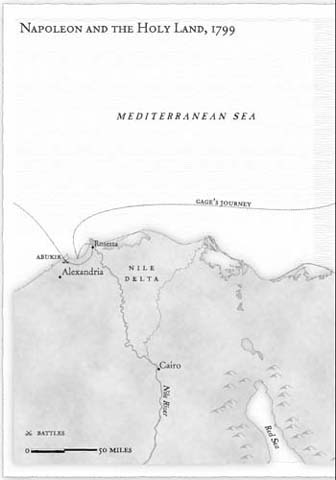

Surviving murderous thieves, a nerve-racking sea voyage, and the deadly sands of Egypt with Napoleon’s army, American adventurer Ethan Gage solved a five-thousand-year-old riddle with the help of a mysterious medallion. But the danger is only beginning….

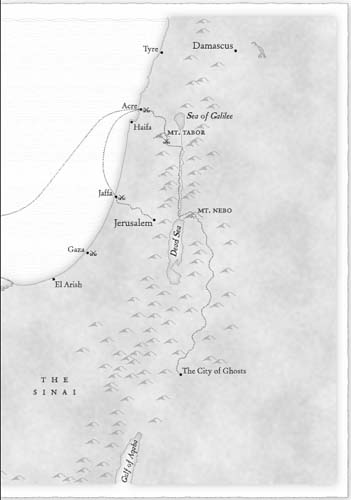

Gage finds himself hurled into the Holy Land in dogged pursuit of an ancient Egyptian scroll imbued with magic, even as Bonaparte launches his 1799 invasion of Israel, which will climax at the epic siege of Acre. Pursuing Napoleon to France, where the General hopes ancient secrets will catapult him to power, the wily and inventive Gage faces old enemies with unlikely new friends, and must use wit, humor, derring-do, and an archaeological key to prevent dark powers from seizing control of the world.

Entertaining and vividly evocative, The Rosetta Key is William Dietrich at his fast-paced, cliff-hanger best. For lovers of stirring historical adventure laden with intriguing mystery and puzzles galore, The Rosetta Key is a terrific thrill ride not to be missed.

William Dietrich

Copyright © 2008 by William Dietrich

To my daughter, Heidi

The possession of knowledge does not kill

the sense of wonder and mystery.

There is always more mystery.

— A

NAÏS

N

IN

ART

O

NE

E

yeing a thousand musket barrels aimed at one’s chest does tend to force consideration of whether the wrong path has been taken. So I did consider it, each muzzle bore looking as wide as the bite of a mongrel stray in a Cairo alley. But no, while I’m modest to a fault, I have my self-righteous side as well — and by my light it wasn’t me but the French army that had gone astray. Which I could have explained to my former friend, Napoleon Bonaparte, if he hadn’t been up on the dunes out of hailing distance, aloof and annoyingly distracted, his buttons and medals gleaming in the Mediterranean sun.

The first time I’d been on a beach with Bonaparte, when he landed his army in Egypt in 1798, he told me the drowned would be immortalized by history. Now, nine months later outside the Palestinian port of Jaffa, history was to be made of

me.

French grenadiers were getting ready to shoot me and the hapless Muslim captives I’d been thrown in with, and once more I, Ethan Gage, was trying to figure out a way to sidestep destiny. It was a mass execution, you see, and I’d run afoul of the general I once attempted to befriend.

How far we’d both come in nine brief months!

I edged behind the biggest of the wretched Ottoman prisoners I could find, a Negro giant from the Upper Nile who I calculated might be just thick enough to stop a musket ball. All of us had been herded like bewildered cattle onto a lovely beach, eyes white and round in the darkest faces, the Turkish uniforms of scarlet, cream, emerald, and sapphire smeared with the smoke and blood of a savage sacking. There were lithe Moroccans, tall and dour Sudanese, truculent pale Albanians, Circassian cavalry, Greek gunners, Turkish sergeants — the scrambled levies of a vast empire, all humbled by the French. And me, the lone American. Not only was I baffled by their babble; they often couldn’t understand each other. The mob milled, their officers already dead, and their disorder a defeated contrast to the crisp lines of our executioners, drawn up as if on parade. Ottoman defiance had enraged Napoleon — you should never put the heads of emissaries on a pike — and their hungry numbers as prisoners threatened to be a crippling drag on his invasion. So we’d been marched through the orange groves to a crescent of sand just south of the captured port, the sparkling sea a lovely green and gold in the shallows, the hilltop city smoldering. I could see some green fruit still clinging to the shot-blown trees. My former benefactor and recent enemy, sitting on his horse like a young Alexander, was (through desperation or dire calculation) about to display a ruthlessness that his own marshals would whisper about for many campaigns to come. Yet he didn’t even have the courtesy to pay attention! He was reading another of his moody novels, his habit to devour a book’s page, tear it out, and pass it back to his officers. I was barefoot, bloody, and only forty miles as the crow flies from where Jesus Christ had died to save the world. The past several days of persecution, torment, and warfare hadn’t persuaded me that our Savior’s efforts had entirely succeeded in improving human nature.

“Ready!” A thousand musket hammers were pulled back.

Napoleon’s henchmen had accused me of being a spy and a traitor, which was why I’d been marched with the other prisoners to the beach. And yes, circumstance had given a grain of truth to that characterization. But I hadn’t set out with that intent, by any means. I’d simply been an American in Paris, whose tentative knowledge of electricity — and the need to escape an utterly unjust accusation of murder — resulted in my being included in the company of Napoleon’s scientists, or savants, during his dazzling conquest of Egypt the year before. I’d also developed a knack for being on the wrong side at the wrong time. I’d taken fire from Mameluke cavalry, the woman I loved, Arab cutthroats, British broadsides, Muslim fanatics, French platoons — and I’m a likable man!

My latest French nemesis was a nasty scoundrel named Pierre Najac, an assassin and thief who couldn’t get over the fact that I’d once shot him from beneath the Toulon stage when he tried to rob me of a sacred medallion. It’s a long story, as an earlier volume will attest. Najac had come back into my life like a bad debt, and had kept me marching in the prisoner rank with a cavalry saber at my back. He was anticipating my imminent demise with the same feeling of triumph and loathing that one has when crushing a particularly obnoxious spider. I was regretting that I hadn’t aimed a shave higher and two inches to the left.

As I’ve remarked before, it all seems to start with gambling. Back in Paris, it had been a card game that won me the mysterious medallion and started the trouble. This time, what had seemed a simple way to get a new start — taking the bewildered seamen of HMS

Dangerous

for every shilling they had before the British put me ashore in the Holy Land — had solved nothing and, it could be argued, had actually led to my present predicament. Let me repeat: gambling is a vice, and it is foolish to rely on chance.

“Aim!”

But I’m getting ahead of myself.

I, Ethan Gage, have spent most of my thirty-four years trying to keep out of too much trouble and away from too much work. As my mentor and onetime employer, the late, great Benjamin Franklin, would no doubt observe, these two ambitions are as at odds as positive and negative electricity. The pursuit of the latter, no work, is almost sure to defeat the former, no trouble. But that’s a lesson, like the headache that follows alcohol or the treachery of beautiful women, forgotten as many times as learned. It was my dislike of hard labor that reinforced my fondness for gambling, gambling that got me the medallion, the medallion that got me to Egypt with half the planet’s villains at my heels, and Egypt that got me my lovely lost Astiza. She in turn had convinced me that we had to save the world from Najac’s master, the French-Italian count and sorcerer Alessandro Silano. All this, without my quite expecting it to, put me on the wrong side of Bonaparte. In the course of things I fell in love, found a secret way into the Great Pyramid, and made the damndest discoveries ever, only to lose everything I held dear when forced to escape by balloon.

I told you it was a long story.

Anyway, the gorgeous and maddening Astiza — my would-be assassin, then servant, then priestess of Egypt — had fallen from the balloon into the Nile along with my enemy, Silano. I’ve been desperately trying to learn their fate ever since, my anxiety redoubled by the fact that my enemy’s last words to Astiza were, “You know I still love you!” How’s

that

for prying at the corners of your mind at night? Just what

was

their relationship? Which is why I’d agreed to allow the English madman Sir Sidney Smith to put me ashore in Palestine just ahead of Bonaparte’s invading army, to make inquiries. Then one thing led to another and here I stood, facing a thousand gun muzzles.

“Fire!”

B

ut before I tell you what happened when the muskets blazed, perhaps I should go back to where my earlier tale left off, in late October of 1798, when I was trapped on the deck of the British frigate

Dangerous

, making for the Holy Land with her sails bellied and a bone in her teeth, cutting the frothy deep. How hearty it all was, English banners flapping, burly seamen pulling at their stout lines of hemp with lusty chants, stiff-necked officers in bicorne hats pacing the quarterdeck, and bristling cannon dewed by the spray of the Mediterranean, droplets drying into stars of salt. In other words, it was just the kind of militant, masculine foray I’ve learned to detest, having narrowly survived the hurtling charge of a Mameluke warrior at the Battle of the Pyramids, the explosion of

L’Orient

at the Battle of the Nile, and any numbers of treacheries by an Arab snake worshipper named Achmed bin Sadr, who I finally sent to his own appropriate hell. I was a little winded from brisk adventure and more than ready to scuttle back home to New York for a nice job as a bookkeeper or a dry goods clerk, or perhaps as a solicitor attending to dreary wills clutched by black-clad widows and callow, undeserving offspring. Yes, a desk and dusty ledgers — that’s the life for me! But Sir Sidney would hear none of it. Worse, I’d finally figured out what I cared about in this world: Astiza. I couldn’t very well take passage home without finding out if she’d survived her fall with that villain Silano and could, somehow, be rescued.

Life was simpler when I had no principles.

Smith was gussied up like a Turkish admiral, plans building in his brain like an approaching squall. He’d been given the job of helping the Turks and their Ottoman Empire thwart the further encroachment of Bonaparte’s armies from Egypt into Syria, since young Napoleon’s hope was to carve an eastern empire out for himself. Sir Sidney needed allies and intelligence, and, after fishing me out of the Mediterranean, he’d told me it would work to both our advantage if I joined his cause. It was foolhardy for me to try to return to Egypt and face the angry French alone, he pointed out. I could make inquiries about Astiza from Palestine, while simultaneously assessing the various sects that might be lined up to fight Napoleon. “Jerusalem!” he’d cried. Was he mad? That half-forgotten city, an Ottoman backwater encrusted by dirt, history, religious lunatics, and disease, had — by all reports — survived only by foisting obligatory tourism on the credible and easily cheated pilgrims of three faiths. But if you’re an English schemer and warrior like Smith, Jerusalem had the advantage of being a crossroad of the complicated culture of Syria, a polyglot den of Muslim, Jew, Greek Orthodox, Catholic, Druze, Maronite, Matuwelli, Turk, Bedouin, Kurd, and Palestinian, all of them remembering slights from each other going back several thousand years.