The Rocks Don't Lie: A Geologist Investigates Noah's Flood (19 page)

Read The Rocks Don't Lie: A Geologist Investigates Noah's Flood Online

Authors: David R. Montgomery

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Religious Studies, #Geology, #Science, #21st Century, #Religion, #v.5, #Amazon.com, #Retail

Although Fleming made it clear that he did not question the occurrence of the biblical flood, he viewed the affair as tranquil enough to leave no geological signature. He considered it futile to look for physical evidence of the Flood.

Fleming also questioned Buckland’s geological interpretations. A global flood would leave the same kind of mud in caves all across Europe. Yet the mud one found varied with the local geology. And if the mud wasn’t washed in from afar, how could the fossils entombed in it have been?

Fleming’s critique continued with summarily dismissing the theory that the elephantlike bones and carcasses found in Siberia and North America came from tropical regions. The intact skeletons ruled out long-distance transport by a violent deluge. Pointing to Cuvier’s anatomical studies, Fleming argued that the thick hair covering mammoth carcasses showed they were native to cold regions. These behemoths were well suited to living where their bodies were found. Mammoths did not confirm the transporting power of the Flood.

Fleming even questioned Buckland’s interpretation of Kirkdale Cave. While he agreed that the cave was an ancient hyena den, he thought that Buckland jumped to conclusions in attributing to a single flood the mud in which the bones were found. A succession of small floods could have deposited the mud.

Reverend Fleming chided geologists for rushing to find evidence of the biblical flood. In his view, misguided efforts to use geology to vindicate biblical interpretations would harm both science and Christianity.

More than Fleming’s scathing critique, new geological discoveries eroded Buckland’s faith in a universal deluge. Most problematic for a global flood was that explorers could find no diluvium in the tropics. Closer to home, it proved impossible to explain the complex stratigraphy of European diluvium through a single event, no matter how catastrophic. Buckland began to reconsider whether his imagination had run wild in his zeal to defend the biblical flood. A decade after Fleming first challenged him, Buckland capitulated when he was asked to prepare a volume commissioned by the estate of the Earl of Bridgewater to illustrate how geology revealed the wonder and wisdom of Creation.

In 1836, Buckland did something few others before him had done in attempts to reconcile geology and the Bible. He pulled a complete about-face when his Bridgewater volume

Geology and Mineralogy

repudiated his earlier view of diluvium. Instead, he endorsed the position that a tranquil Flood did little to Earth’s surface, long after earlier catastrophes laid down fossil-bearing rocks and surficial deposits. Citing recent discoveries, Buckland advocated caution in trying to use the geological record to support literal interpretations of Genesis.

The disappointment of those who look for a detailed account of geological phenomena in the Bible, rests on a gratuitous expectation of finding therein historical information, respecting all the operations of the Creator in times and places with which the human race has no concern; . . . the history of geological phenomena… may be fit matter for an encyclopedia of science, but are foreign to… a volume intended only to be a guide of religious belief and moral conduct.

7

Although Buckland still maintained that a geologically recent inundation overwhelmed the northern hemisphere, his earlier confidence that it was the biblical flood lay shattered. He could no longer attribute fossils to Noah’s Flood. Fossils were found in strata that accumulated slowly over long periods of time. Even the surficial deposits recorded more than one event. Buckland had abandoned Noah’s Flood.

Despite his change of mind, Buckland had no concern that geology and revelation would prove inconsistent.

Geology has shared the fate of other infant sciences in being for a while considered hostile to revealed religion; but, when fully understood, it will be found a potent and consistent auxiliary to it, exalting our conviction of the Power, and Wisdom, and Goodness of the Creator.

8

Secure as ever in his faith in both nature and the Bible, Buckland maintained that the question is not

“the correctness of the Mosaic narrative, but of our interpretation of it.”

9

In a philosophical turnabout, Buckland shifted from using geology to shore up a literal interpretation of the Bible to arguing that biblical interpretations could be tested through consistency with geological observations.

Coming from a conservative man of the cloth, Buckland’s Bridgewater treatise drew immediate attacks from fellow clergy appalled by his recantation of geological support for the biblical flood. Outraged traditionalists who insisted on interpreting the Bible literally railed against this compelling dismissal of scriptural geology by a ranking clergyman steeped in Anglican orthodoxy.

What led to Buckland’s stunning reversal? To a great degree it was his former spellbound student, Charles Lyell.

Born into a life of privilege the year James Hutton died, Lyell grew up exploring the New Forest in Hampshire, where his father pursued botanical studies and encouraged his son’s interest in the family’s extensive natural history library. Raised an Anglican, Lyell read Bakewell’s just-published geology textbook in 1816, the year he enrolled at Oxford to study classical literature and law. Lyell was particularly struck by Bakewell’s concept of a world much older than generally supposed based on a literal reading of Genesis. Equally intriguing to him, this unconventional idea came from the pen of someone who believed geology revealed the Creator’s grand design.

Lyell attended Buckland’s Oxford lectures each spring from 1817 to 1819. He came to accept that the biblical chronology referred to the time since the creation of people. Who could know how much time had passed before then?

Buckland’s enthusiastic endorsement ensured Lyell membership in the Geological Society of London once he graduated. Society members overwhelmingly rejected Hutton’s view of great cycles of gradual change driven by processes like those operating at present. Most advocated Cuvier’s view of earth history as a series of violent catastrophes. On a visit to Paris the previous year, Lyell examined Cuvier’s collection of fossils, describing them as “glorious relics of a former world.”

10

After graduation, Lyell divided his time between reading for the bar and traveling through Europe. Visiting Paris again in 1823 as a representative of the Geological Society, he met Constant Prévost, a colleague of Cuvier, who believed that the alternating freshwater and marine strata of the Paris basin were deposited gradually in a coastal inlet that periodically turned into a freshwater lake. Perhaps geological change could occur through observable causes, if given enough time.

The following year, in the fall of 1824, Lyell visited sixty-three-year-old James Hall at his estate on the Scottish coast. Now about the age Hutton was when they first sailed to Siccar Point, Hall took Lyell there to absorb Hutton’s insight through his own eyes. Seeing firsthand how earth history involved a lot more time than conventionally thought, Lyell began to believe that gradual changes could shape the land.

That same year, Lyell joined Buckland for a geological excursion through Scotland. Although it may have been clear to both that their views had started diverging, neither could have known that within a decade the apprentice would dethrone the master.

Lyell was not particularly interested in questioning religious views. Like many of his peers, however, he was deeply concerned about the effect that ignoring geological evidence could have on both science and religion. In 1827, he concluded a review of George Poulett Scrope’s

Memoir on the Geology of Central France

with an appeal for interpreting Genesis broadly and letting the rocks speak for themselves:

We must recollect that the Mosaic narration is elliptical in the extreme, and that it makes no pretensions whatever to supply those minute scientific details which some would endeavour to extort from it.

11

Lyell was echoing Augustine in believing that it would be hard to convince rational men to follow a religion that denied things one could see for oneself.

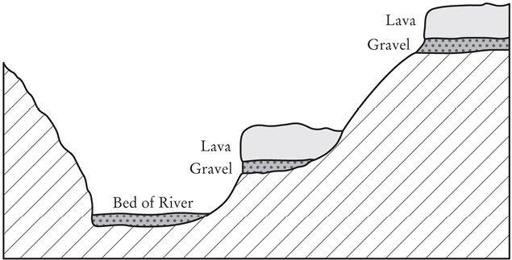

Scrope’s book was the culmination of extensive fieldwork in the Auvergne region, where dozens of conical hills made of loose piles of volcanic cinders overlook acres of black basalt. Deep valleys were carved into stacked lava flows on which these delicate cinder cones stood. Identical sequences of lava flows exposed in the walls on opposing sides of individual valleys proved that the river cut down into the lava. Lyell was intrigued by Scrope’s description of how the lava flows buried the river gravels now exposed in the valley walls. Scrope’s careful observations left no doubt that the lava had repeatedly filled a valley that the river just as often reexcavated. The layers exposed in the cliffs were not deformed and there was no evidence of catastrophic disruption. The valley-filling lava flows could be traced back to loose cinder cones sure to have been swept away by a flood capable of carving into hard rock.

Lava flows emplaced over buried river gravels in Auvergne, France

(

based on Charles Lyell’s 1833

Principles of Geology

, volume III, figure no. 61, p. 267

).

The following May, Lyell set off to explore the region firsthand, accompanying the influential Scottish geologist Roderick Murchison on an excursion through France. They visited Scrope’s outcrops and studied the relationships between cinder cones, basalt flows, and river terraces. It quickly became clear to Lyell that a single flood could not have carved modern topography. Rivers slowly carved their own valleys.

From Auvergne, they traveled down the Rhone Valley to compare its rocks with those of the Paris Basin. Proceeding south into northern Italy, they traveled from Bologna to Florence and on to the Zoological Museum in Turin. Lyell realized that the rocks in the different parts of the regions they had just crossed had different fossils. Here was a formative realization for one who had never set out to become a geologist.

Fossils could be used to reliably assess the age of strata in southern Europe, something that could not be determined from mineral composition alone. The fossils in the younger rocks at the top of the regional geological pile were more like the modern fauna than were the fossils in the older rocks deeper in the section. The comings and goings of species from the fossil record could be used to track geologic time. Lyell was hooked. Here was the key to the grandest puzzle. The fossils in different rock formations could be read to tell geologic time. If you knew the mix of fossils in a rock formation, you could confidently deduce its age relative to other formations.

When Murchison returned to London in August, Lyell traveled on to Sicily, ending his career as a barrister. He was now a geologist, by accident rather than design. More than anything else his exploration of European geology convinced him of the enormous span of geologic time and that a global flood was not responsible for shaping the modern landscape. Perhaps Hutton was right after all. Maybe slow, steady change was the pace at which the world worked.

On his way back to England, in February 1829, Lyell stopped in Paris to compare the fossils he had picked up with those in the collections of French geologists. The proportion of still-living species increased farther to the south—and higher in the regional stack of rocks. Older rocks, lower down in the regional pile, held more species not represented in the modern fauna. This didn’t square with the traditional biblically inspired view that, except for the Flood, everything’s been the same since the Creation.

The trip through France and Italy convinced Lyell to try to sway public opinion away from the misconception that Genesis precluded the immensity of geologic time. It was an ambitious goal. Geological findings that contradicted conventional biblical interpretations weren’t common knowledge, and geological audiences favored Cuvier’s grand catastrophes to explain the geologic record. Few favored Hutton’s style of uniformitarian thinking in which everyday processes slowly shaped the world. Writing for two audiences, Lyell tried to counter the dominance of catastrophist thinking among his colleagues without shocking the general public accustomed to the idea that Noah’s Flood resurfaced our six-thousand-year-old planet. In 1830, he put his legal training to work in his

Principles of Geology

, building up an argument and defense against the reactionary outcry sure to follow.

In presenting his case, Lyell began with a history of geology that turned the uniformitarian-catastrophist debate into a simplistic choice. Things either happened catastrophically or they happened gradually. Casting the debate between uniformitarianism and catastrophism as between rationality and superstition, he decried the tendency of previous generations to conjure up grand catastrophes when the steady action of processes still operating today could explain the world.