The Rocks Don't Lie: A Geologist Investigates Noah's Flood (10 page)

Read The Rocks Don't Lie: A Geologist Investigates Noah's Flood Online

Authors: David R. Montgomery

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Religious Studies, #Geology, #Science, #21st Century, #Religion, #v.5, #Amazon.com, #Retail

In his hallmark contribution to geology, Steno adopted guiding principles for interpreting the history of rocks that he intended to be so simple, clear, and transparent that no one could dispute them. The first simply states that the layers at the bottom of a pile of sediment were laid down first, and therefore were oldest. The second holds that sedimentary layers are deposited horizontally. These simple principles allowed him to start piecing together the story of the Tuscan landscape. Defining how to determine the relative age of strata and past events opened the door to deciphering earth history. It was Steno’s distinction between primary and secondary rocks—between crystalline rocks he thought were made at the initial Creation and layered rocks that formed later from detritus eroded off the original rocks—that set the stage for the development of a geological time scale.

By the spring of 1668, Steno’s trips into the hills convinced him that the ancients were right about the nature of fossils. That summer he submitted his findings about fossils and Tuscan geology to the church’s censors, who routinely vetted the theological acceptability of scholarly discoveries, opinions, and interpretations about the natural world. Although this meant his

Dissertation on Solids Naturally Enclosed in Solids

wasn’t published until the following year, Steno did not need to worry about meeting Galileo’s fate. His interpretation of geological evidence as faithfully recording the biblical flood placated the church even though he broke with prior tradition to interpret earth history through studying rocks and fossils rather than scripture.

In contrast to the fanciful theories of his better-known contemporaries, Steno’s interpretation of how Noah’s Flood shaped the Tuscan landscape was rooted in field observations. After laying out how fossils got into rocks, he described the sequence of events he read in the hills around Florence.

He concluded there were six periods in earth history that corresponded to the biblical account. He found no fossils in the lowest, and therefore oldest, layers. So these rocks formed right after the Creation, when water covered the world. Before the creation of life, sedimentary rocks lacking fossils settled out in this primeval sea, laid down as horizontal strata. As these newly deposited rocks emerged to form dry land, Steno thought subterranean fire or water ate out huge caverns in the underlying rock. When these great caves collapsed to produce valleys, it triggered Noah’s Flood as the seas rushed down to fill the new lowlands. After more sediment settled in the new, lower-elevation sea the whole process repeated, resulting in a second round of cavern collapse that produced modern topography and the tipped-up rock layers within. It was Steno’s way of making sense of what he observed given his faith in the historical reality of Noah’s Flood.

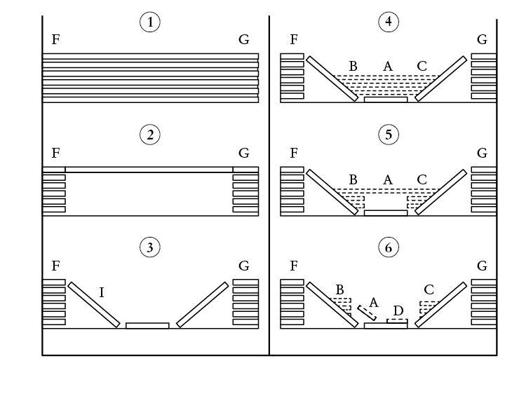

Steno’s six-stage model for the formation of the landscape around Florence, involving: (1) precipitation of fossil-free sedimentary rocks into a universal ocean; (2) excavation by fire or water of great subterranean caverns beneath Earth’s pristine surface; (3) collapse of undermined continents to produce a great flood (Noah’s Flood); (4) deposition of new layered (sedimentary) rocks containing fossils in inundated valleys; (5) continued undermining of younger rocks in valleys; and (6) another round of collapse to create the modern topography.

Steno’s version of Tuscan geologic history fit neatly into the traditional interpretation of Genesis as historical truth. But where did the floodwaters come from? Steno’s theory combined various natural causes to explain Noah’s Flood. Debris from Earth’s collapsed outer crust blocked the passages that pushed seawater back up into the mountains. While the sea overflowed, rain fell incessantly. Rivers dumped eroded soil into the sea, making it overflow all the more. In other words, Steno gathered the floodwaters from everywhere he could—sea, sky, and the subterranean abyss. While much of what he deduced about how rocks form and how fossils become part of them stood the test of time, his interpretation of the geologic history of the Tuscan landscape did not.

This would not have bothered him. Steno viewed science as a spiritual endeavor, a quest for better understanding God and better interpreting scripture. Seeing humility as important in both science and religion, he eventually became disillusioned with his colleagues’ petty rivalries, arrogance, and lust for fame and converted to Catholicism on All Souls’ Day, November 2, 1667.

For months he had been agonizing over whether to abandon his native faith and join the Catholic Church, troubled by the problem that Protestants and Catholics alike were convinced that theirs was the one true faith. Both could not be right. The dichotomy of these two worldviews haunted Steno and eventually led to a life-changing decision. The root of his angst was the inclination of Protestants toward literal interpretation of the Bible versus the allegorical and metaphorical lens Catholics used to address obscure passages and internal inconsistencies. And which version of the Bible was authoritative—Hebrew, Greek, or Latin? Not trusting standard translations, Steno applied his analytic powers to compare the theological claims of Protestants and Catholics against original Hebrew and Greek manuscripts in the Medici library.

In the end, however, it was not rigorous scholarship that convinced him to convert but a chance event while walking down a Florence street. Meditating on the issue, he heard a woman from an open window call for him to cross over to the other side. In addition to the implied warning about what she was about to toss out onto the street below, he interpreted this as a sign from God.

He converted, became a priest, took a vow of poverty, and gave up his studies as a sacrifice to God. Equal parts genius and saint, he routinely gave his money to the poor and often went without food himself, sometimes by choice or because he was too broke to buy it. He annoyed wealthy parishioners and fellow clergy by vociferously advocating for the poor, even selling his bishop’s ring to help feed the hungry. When Steno died in 1686 his worldly possessions consisted of a few worn-out garments. Three centuries later, in 1988, Pope John Paul II beatified him, on October 23, the day that Bishop Ussher, a contemporary of Steno’s whom we’ll meet later, famously claimed as Earth’s birthday.

Although Steno recognized some of the challenges that his geologic principles presented to conventional interpretations of scripture, he did not see the potential for fundamental conflict between science and Christianity. Like most of his peers, he thought reason helped illuminate the wonder of Creation.

Read by few in his own time, Steno’s ideas caught on only after they were tested and popularized by other natural philosophers eager to use formal principles to enhance their understanding of God’s greatest work, Earth. Ironically for a man of deeply conventional faith, the foundational principles he developed to explain the role of Noah’s Flood in shaping the Tuscan landscape eventually undermined both the traditional biblical timeline for the Creation and the reality of a global flood.

Although geologists recognize Steno as both a pivotal and an inspirational figure, we tend to overlook the extent to which he interpreted geologic features as evidence that Noah’s Flood reshaped the world. Instead, we emphasize his faith in how rocks tell the story of the world, while Steno himself was striving to read God’s other book—nature. After Steno, rocks could tell their own story. The natural world and how it worked could frame—and conceivably limit or refute—theological options for how to read the biblical stories of the Creation and Noah’s Flood.

Although Steno faded into obscurity in his own day, his principles have stood the test of time. In contrast, the prominent Anglican reverend and Cambridge theologian Thomas Burnet, who also worked to square geological features with Noah’s Flood, left a different legacy. He proposed the most influential seventeenth-century explanation of Noah’s Flood but is remembered today for the way his faith in how he read the Bible spawned an overly imaginative theory. In 1681, his elegant

Sacred Theory of the Earth

sought to address two familiar problems: where did the floodwaters come from and how did mountains form?

At Cambridge, Burnet was taught that Moses intended for the masses to interpret Genesis literally and for elite priests to read between the lines. Burnet took this view to heart when, at the age of thirty-five, he set off across Europe on a grand tour. Coming from the verdant English countryside, he was shocked by the disorder he saw in the mountains. He thought the Alps were towering wrecks composed of “wild, vast and, indigested heaps of Stones and Earth.”

2

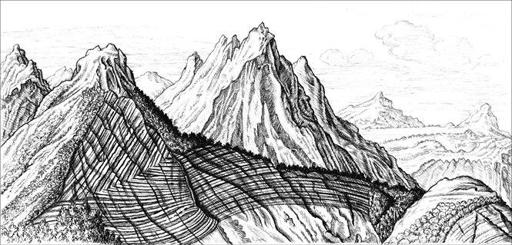

The confusing internal structure of the Alps forced Burnet into a theological crisis. Believing that God made all things in beauty and proportion, he found the Alps a chaotic place lacking order or design. He could not believe God’s divine hand would create such monstrous forms. Surely the Creator would make a beautiful, symmetrical world—something more like Burnet’s England. Mountains must be the remains of a wrecked planet, crumbling ruins of an originally perfect sphere. Just what had happened?

Illustration of the deformed interior structure of the Alps visible in the pattern of rock outcroppings

(

by Alan Witschonke based on lowermost panel of plate XLVI of Johann Scheuchzer’s

Sacred Physics

(1731

)).

After three years of travel, Burnet returned to England committed to determining how God set up a perfect world destined to disintegrate. He carefully estimated both the amount of water in the oceans and how much it would take to submerge the highest mountains. There was nowhere near enough water on the planet. It would take eight times the volume of the world’s oceans. Even forty days and nights of rainfall at the astounding rate of two inches an hour would only amount to 160 feet of water. Burnet refused to invoke miracles. To assert that God simply made more water when and where He needed it was too easy, to “

cut the Knot when we cannot loose it

.”

3

There had to be another source.

Then it hit him. The world was completely different before the Flood. The water in today’s oceans would cover a smooth, topography-free globe to a depth of about the biblically proscribed fifteen cubits (just under twenty-five feet). And if Earth was originally featureless, there was no ocean aboveground. Instead, a primordial ocean must have existed underground.

In Burnet’s view of the Creation, God commanded the elements to sort out by density, the heaviest sinking to the center and lighter stuff forming outer layers. Gravity then settled the original chaotic mass into a dense core surrounded by a layer of water and an outer envelope of air. A greasy floating layer eventually coalesced into an outer crust like the shell of an egg. In this way, disorganized chaos became a habitable planet. Close to a perfect sphere, the primitive Earth had the perfect shape for a perfect paradise, something worthy of divine creation.

Burnet’s early Earth also enjoyed an endless summer. And while this may have sounded like paradise to an Englishman, all that sunshine gradually warmed the planet, causing it to expand and form fissures at the base of the crust. It also began to dry and crack the planet’s outer shell. As the great subterranean ocean heated up, its expanding vapors pressed against the planet’s weakened crust.

Burnet’s imagination ran with the idea as he proposed that divinely timed cracks propagated to the surface right at the peak of human wickedness, just after Noah finished building his ark. When the outer crust collapsed into the interior sea, humanity’s ancestral paradise foundered into the abyss. Water shot high into the air and sloshed around for months, creating and sculpting topography. This left the planet in ruins, rugged mountains replacing smooth plains as tumultuous waves resurfaced the world.

To get rid of all the water, Burnet simply had it drain back down into cracks in the seafloor. Deep caves and volcanoes proved the presence of cavities beneath the continents. Shouldn’t there be similar caverns beneath the seas? A subterranean drain also provided a handy explanation for how the seas never overflowed even though rivers drained continuously into them (although evaporation, of course, turned out to provide a better explanation).