The Road to Ubar (34 page)

Authors: Nicholas Clapp

Soon thereafter, someone brought a sandstone chess set to Shisur, as the site was now called, and in a tower of the ruined fortress matched wits in a game that, like the rise and fall of this lonely outpost, ended with the word

shahmaut

â"To the king

(shah),

death

(maut).

" Or, as we have anglicized it, "Checkmate." The chess pieces were scattered about and forgotten. This may have happened when the fortress was attacked and burned around 940, probably by the Hadramis, who had for a very long time sought to control the 'Ad and, thereafter, the Mahra. In the Citadel, the defenders had stashed but did not use hundreds of iron-tipped arrows (discovered by Juri in 1993). What would the Hadramis have gained? Little but the settling of an ancient score.

In medieval times, Shisur had to have been a melancholy place. In 1221, Ibn Mujawir, a merchant of Baghdad, recorded the final abandonment of the old trade routeâthe road to Ubarâacross the Rub' al-Khali. Travelers Marco Polo and Ibn Battuta wrote of the Dhofar region but said nothing of a city out in the desert (although Ibn Battuta, somewhat sarcastically, mentioned the remnants of the realm of the 'Ad).

The final incident of note in Ubar's history came in the early 1500s when the Hadrami warlord Badr ibn Tuwariq appears to have desultorily rebuilt the old Citadelâand was subsequently credited by the region's bedouin for constructing the entire fortress. The site's true identityâand any hint of all that had happened in and around its wallsâwas thereafter obscured. Sometime later the bedouin began to believe that Ubar lay hidden in the dunes of the Rub' al-Khali, for that's where they found Neolithic artifacts and that's where the old road ran.

Just when all remembrance of Ubar was fading from bedouin memory (displaced by fascination with a world of Toyotas and Walkmans), an odd chain of events brought an odd collection of adventurers to Shisur. They dug and unearthed an ancient fortress rising above what once was a tent city.

***

Strata and shards and carbon-14 dates have subsequently given a new reality to the preaching of the prophet Muhammad, to the storytelling of streetcorner rawis, even to the doggerel of contemporary bedouin. A remote desert ruin might have forever remained just that, but for their words...

Epilogue: Hud's TombAs old as 'Ad...

Roast flesh, the glow of fiery wine,

to speed on camel fleet and sure...And ninety concubines, of comely breast

And rounded hips, amused me in its halls...O delegation of drunks, remember your tribe...

Wealth, easy lot...

An ignominious punishment shall be yours this day, because you behaved with pride and injustice of the earth and committed evil...

Sons and thrones are destroyed!...

Now all is gone, all this with that...

Checkmate...

It was a great city, our fathers have told us, that existed of old; a city rich in treasure...

At the end of life there is nothing but the whisper of the desert wind; the tinkling of the camel's bell...

4

I

N THE

S

PRING OF 1995,

Juris Zarins and his crew wrapped up their archaeological program in Dhofarâand in neighboring Yemen, Kay and I, accompanied by our photographer friends Julie Masterson and David Meltzer, journeyed to where the myth of Ubar came to rest: the tomb of Hud.

Along the way we thought and talked about something that, we saw in retrospect, had underscored our quest for Ubar and the People of 'Ad:

the relationship between myth and landscape.

This relationship has been notably explored by the Australian architect and anthropologist Amos Rapoport, who listened to the stories of Australian bushmen and mapped their world as a mythological landscape. Rapoport perceived that a tribe's cherished mythsâof its origin, its meaning, its purpose in the worldâwere "unobservable realities" that sought expression in "observable reality." Land and landmarks made myth real and validated a tribe and its heritage. To a seminomadic, materially rootless people, stories of their ancestors can mean as much as food and water.

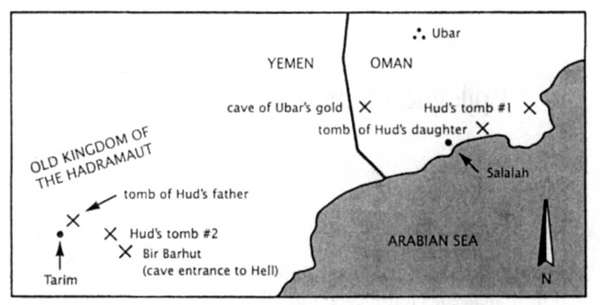

Mythological landscapes can be found the world over. There are the kachina-populated mesas and valleys of the Hopi, the Buddhist caves of central China, the landscape of grief and miracles in the Holy Land. As we roamed Oman and then Yemen, it became apparent that southern Arabia had three distinct tiers of mythological landscape. There were the sites of fondly recalled bedouin raids and battles, proof of their daring and prowess. Next there were the many and dreaded haunts of djinns. And, lastly, there were sites associated with patriarchs and prophets holy to Islam.

1

This last landscape harked back to the time of Ubar and its principal players, especially the prophet Hud.

Ubar's mythological landscape

Of the two tombs of Hud appearing in this landscape, the oldest and perhaps original one is in an isolated corner of the Dhofar Mountains. It is marked on al-Idrisi's map of Arabia from 1154.

2

We were told by the Omanis that it was a forlorn site and that nobody goes there now, which may or may not be so. In the 1930s, Bertram Thomas wrote of the bedouin perception of the site's awesome power: an oath sworn upon Hud's grave held more weight than one sworn on the Koran or in the name of the prophet Muhammad or of Allah himself. If a guilty party was dragged to the shrine, Thomas recounted, he would usually confess rather than profess his innocence and risk Hud's awful avenging power. Had not Hud brought down the wrath of God on the People of'Ad?

Regrettably and inexplicably, Omani government restrictions prevented our visiting this site, so David, Julie, Kay, and I found ourselves on our way to a perhaps less authentic, but considerably better known, Hud's tomb, at the far end of the valley of the Hadramaut in Yemen.

3

To get there from the capital, Sana'a, we drove through mist-shrouded highlands, across a land of soaring red rock mesas, then past a thousand salmon-orange dunes drifting into the sea. On the fourth day, at the old port of Mukalla, we turned inland and snaked up onto a drab, featureless tableland. We drove across it for the better part of a day, until suddenly the ground opened at our feet, a great rift nearly a thousand feet deep and one to two miles wide. This was the valley of the Hadramaut, the largest and surely the most breathtaking wadi in all Arabia.

We descended into a valley of foliage and flowers, surrounded by the buzzing of bees. (Their honey is unbelievably tasty.) Everywhere there were neatly furrowed fields tended by black-robed, veiled women wearing pointed straw hatsâwitch hats. The Hadramaut's villages, spaced every few miles, were remarkable: the densely clustered mud-brick dwellings rose four, six, eight stories high. As the last pale light of the day retreated up the towering cliffs that enclosed the valley, a thousand and more lamps glowed in the windows of Shibam, a town where five hundred buildings, soaring 120 feet in the air, crowded into less than half a square mile. We were in the valley of the world's first skyscrapers.

4

In the next few days, we were awed by the valley of the Hadramaut's dramatic setting and fanciful, spectacular architecture. We were also a little uncomfortable. We had come upon an ancient way of life, ordered and conservative, with traditions kept very much to itself. Also, steeped in Ubar lore, I found it hard not to feel that we were in alien territory, the land of the Hadramis, who had long threatened and likely pillaged our erstwhile if wicked city. I had to remind myself that this happened fifteen hundred or more years ago.

We worked our way to the Hadramaut's most distant major settlement: Tarim, city of 365 mosques, once known throughout Islam as "the city of wisdom and learning." In late medieval times, Tarim had been celebrated for its great libraries, and we hoped, though we had been forewarned to the contrary, that one of them might still magically exist and hold a long-lost copy of Ibn al-Kalbi's

History of 'Ad, the Beginning and the End

or the ten lost volumes of al-Hamdani's

Book of the Crown

(documenting the early civilization of Arabia), or undiscovered early tales of the

Arabian Nights.

But we knew that in the late 1700s, fanatic Wahhabi tribesmen had overrun Tarim and ripped to shreds and burned its books. What they missed had been destroyed by later infestations of white worms. Learning and wisdom had become ashes and dust.

Even so, there were reverberations of the distant past in the valley's everyday life. Sacrificial blood consecrated the construction of buildings; white paint splashed around windows warded off djinns; the social structure of towns, clans, and families was as it had been hundreds, perhaps thousands, of years ago. And everyone was aware of the fate of Ubar and the People of 'Ad. The given name Abd al-Hudâ"servant of Hud"âwas common in the valley, and leading families claimed Ubar's prophet as their direct ancestor.

Every year Tarim's leading families oversee a three-day pilgrimage to Hud's tomb, fifty miles to the east. Reportedly, ten to twenty thousand souls travel to the tomb, many of them walking the entire way. Some oldsters, we were told, hobble a mile or two every year, intent on eventually accumulating the full fifty. It is a little-known Arabian event, yet in size and fervor it is second only to the hajj to Mecca. We would have given anything to witness this but had understood that it was off-limits to non-Moslems. Indeed, only Moslems who had roots in the Hadramaut were truly welcome.

We were told, though, that it would be no problem for us to visit Hud's holy precinct at any other time. And so on an April morning, awakened by the echoing calls of Tarim's many muezzins, we were on our way. It was a warm, sunny day, and we were all in good spirits, especially Hussein, our Yemeni driver, who kept time by thumping the stock of his prized Kalashnikov automatic rifle as he sang along with a newly purchased cassette of Hadrami music. East of Tarim the valley of the Hadramaut was quite wide and relatively uncultivated. We passed through several tiny villages but saw only a few distant figures. It was hard to imagine the dirt track clogged with the enormous procession of pilgrims that had passed this way a month before, as they annually did in the second week of the lunar month of Shaban.

By good fortune, there is a detailed account of the pilgrimage to Hud's tomb, written by Arabist-anthropologist Robert Serjeant in the late 1940s. As he described it, the procession out across the desert from Tarim was a high-spirited, often boisterous affair, with the pilgrims frequently breaking into song. There was the song of the cloud that accompanied Hud on his travels, ever shielding him from the sun. There was the song of the trapped gazelle who asked Hud to free her so she might feed her young. There were quaint songs, insulting and bawdy, for the villages marking the way. One ditty deemed the rock-hard ground at As-Sallalah uncomfortable for sleeping, fit only for buggery:

You camel men, go, abuse each other,

At As-Sallalah go meet your lover.

Passing through the tiny town of Khon, the pilgrims sang:

O Khon, no girl in Khon is chaste,

Where married and unmarried women fornicate.

5

Through As-Sallalah and on through Khon we drove. We turned off into the Wadi 'Aidid, a tributary of the Wadi Hadramaut. Far ahead, set on a rise at the foot of a towering red rock cliff, we caught sight of a glistening white dome. As we drew closer, we saw that the tomb overlooked a fair-sized town, which proved to be immaculately well tended and clearly prosperousâbut totally deserted. No dog barked, no bird sang, no retainer looked after things. It was inhabited but three days a year, during the pilgrimage.

From the white, silent town, a broad staircase led up to an open-air prayer hall built around a giant boulder. A further flight of stairs ascended to the tomb itself, a graceful dome in which was enshrined a whitewashed, squared-off rock, split by a fissure. It was the sarcophagus of the prophet Hud. He was evidently a very tall man, for his sarcophagus extended beyond the confines of the building and a good ninety feet up the hillside behind it. The tomb's walls were speckled with colored dots, wads of paper conveying the prayers and pleas of recent pilgrims.

Though augmented by buses and pickups, this year's procession from Tarim, we had been told, was much as Serjeant had described it in the 1940s. Passing an outcropping called the Rock of the Infidel Woman, pilgrims shouted, "God curse you, infidel woman," and, better yet, peppered it with bursts of rifle fire. Their arrival at the town had prompted chanting, shouting, and more shooting. The atmosphere was festive, harking back to the great fairs of pre-Islamic Arabia, where the people of the desert and the cultivated lands, herdsmen and farmers, gathered to exchange goods, race camels, and honor not only Hud but, as a present-day Hadrami has written, "invoke peace on all the prophets of importance, the four perfect women, the archangels, and the gardener of Paradise."

6