The Road to Ubar (24 page)

Authors: Nicholas Clapp

W

eek two at

S

hisur

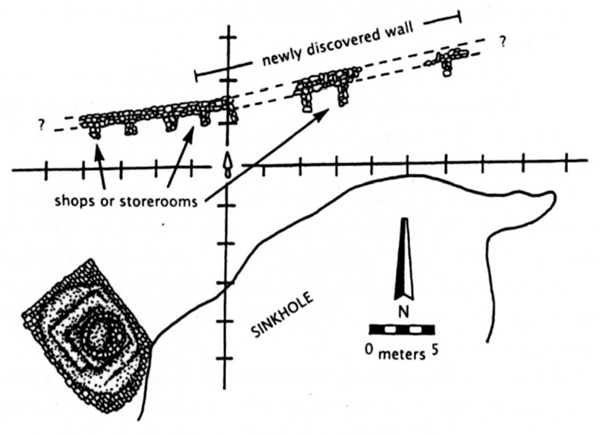

... We dug. Slowly, with trowels and brushes. Excavation wasn't a process to be rushed. If there was anything here, it would be revealed in good timeâand it was. At depths ranging from a few inches to a few feet, Juri and his students uncovered the stone foundation of what was once a wall. It ran along the ridge that had appeared to be a natural feature. The three small rooms Juri had noted backed onto the wall. He speculated that they could be storerooms or merchants' stalls: "In souks all over Arabia, you still see shops laid out like this."

Our student diggers were each assigned a three-meter square. As they carefully excavated, they recorded the positions of rocksâsome of which were clearly the foundations of a wallâand noted subtle changes in the composition of the sand and dirt. Their initial modest finds included bits of worn orange pottery and tiny bones (probably mice). Juri circulated about, answering questions ("Is this worth anything?" "No"), making suggestions ("You can pull those little rocks out. Not structural"), and often pitching in with the spadework.

Four days after Christmas, poking about in an untouched square,

North ridge 2: wall revealed

Juri unearthed a shard. Easily overlooked, it was dull gray, a contrast to the orange ware he and his students had been finding. Picking it up, he turned it over, then over again. "Nice early piece" was all he could say, for he was stunned. This "nice early piece" was a fragment of a Roman jar, either brought here by caravan or copied in Arabia as "imitation ware." In either case, "early" meant before the time of Christ, possibly as early as 300

B.C.

Excavation intensified. To be sure that nothing was missed, each square's sand and dirt was collected in black plastic buckets and carted over to a sifting screen, where it proved, more often than not, to be sand and dirt, nothing more. Much of the screening fell to Absalom, one of three enterprising Baluchi laborers who had queried Ran at the coast, made their way to Shisur, and been hired. When a student spread the contents of a bucket on Absalom's screen, he shook it only briefly before answering repeated inquiries of "Anything? Anything yet?" with a dark Baluchi frown. Archaeology was not for the impatient.

It was student Julie Knight who found the next distinctive bit of pottery. Without reference texts, Juri couldn't be sure what it was, but guessed it was Greek (or imitation Greek), datable to 100

B.C.

at the latest and 400

B.C.

at the earliest.

In the coming days, a few shards were to become hundreds. More Greek and Roman pieces, and some that Juri could not immediately identify but thought might have come from the eastern part of the classical world, from Syria or perhaps Persia. The settlement at Shisur was no longer five hundred years old; it was well over two thousand years old!

With its varied ware, Shisur began to reveal its past. Its inhabitants must have prospered, for they could afford some of the best utensils the ancient world offered. Beyond that, they were themselves inventive, producing orange pottery decorated, frequently, with a motif of dots inside circles. Juri had found such ware at Khor Suli on the coast, probably out in the Rub' al-Khali (a piece so worn he couldn't be sure), and now here. He believed the style was unique to this part of Arabiaâand possibly a hallmark of the People of 'Ad.

Dot-and-circle shard

Now we dared whisper, "Ubar?" Kay, raised in the South and familiar with things like jinxes and spells, said we should be careful and not risk spooking our good fortune. If at this point we went around thinking we had found Ubar, it could somehow make the place

not

be Ubar. If what we had found was too good to be true, maybe it wasn't. And there was now a nagging question: was our site a backwater outpostâor was it, as Ubar must have been, a significant and major settlement?

Week three at Shisur

... Monday passed without incident. On Tuesday the wall that appeared to extend east from the existing fort puzzled Juri. In Rick Brietenstein's square, instead of continuing straight on, the wall made an unexpected curve. "Comes off clean," Juri puzzled, "and curves around." He and Rick followed the wall stone by stone, questioning whether they were being deceived by collapsed masonry or, worse yet, a natural line of rocks. But no, the wall was distinctly there, curving around like a horseshoe, then abruptly resuming its prior alignment.

North ridge 3: tower discovered

Juri straightened up, stepped back. And it came to him. "You know what? A tower. Looks like we have ourselves a tower."

We clambered up on the roof of a Discovery for a high-angle view of the excavation. As Amy Hirschfeld focused her Nikon, juri had Rick chalk an ID slate: "DAD [Dhofar Antiquities Dept.]

TOWER

#1." From the width of its stone foundations Juri estimated that the tower might have risen as high as thirty feet.

"A tower, think about that," juri said. "You don't just build one in the middle of nowhere. You have a wall here, then a tower, then you're going to have more wall, more towers..." Here at Shisur a tower would almost certainly have been a component of a large structure: a fortress that protected the site's water supply and guarded a season's store of frankincense.

Ancient furnace

Sure enough, almost simultaneously, farther down the ridge Jean England unearthed in her square the foundations of a second tower, "DAD

TOWER

#2." Larger than the first and circular, it marked the fortress's northeast corner. It contained traces of an interior stair and sheltered what appeared to be a small furnace outfitted with stone reflecting vanes to achieve higher than normal temperatures. It was difficult to say what the furnace had been intended for. It wasn't for smelting metal, for there was no evidence of slag. It might have been used, we thought, to process frankincense.

3

North ridge 4: excavation completed

Juris hunch to excavate the site's north ridge could not have been more on target. We had uncovered the north wall and towers of an ancient fortress.

As, at dusk, Baheet issued a call to prayer from Shisur's minaret, I was prompted to read, as I had read many times before, the Koran's sura "The Dawn"..."Have you not heard how Allah dealt with 'Ad? The people of the many-columned city of Iram, whose like has never been built in the whole land?"

If this was Iram/Ubar, where were the columns? One explanation, I thought, lay in the Arabic word , pronounced

, pronounced

imad.

In contemporary usage, it means pillar, but older definitions were broader. In George Sale's 1782 edition of the Koran, the first in English, the line in question is translated as "The people of Iram, adorned with lofty buildings." In the ancient world, lofty buildings would most likely have been what Juri was finding: towers.

4

The prophet Muhammad, incidentally, decried "lofty buildings." In a saying regarding "Signs of the End" (that is, the end of the world) he condemns them for presuming to soar higher than mosques. Given Ubar's mythical repute for arrogance, how fitting that it be known for its "lofty buildings," its towers.

As the week progressed, Juri and his students unearthed the footing of a third tower and more of the fortress wall (see endpaper site plan).

We fell into a routine. Up at first light, we had breakfast in our largest room, where Kay's Christmas tree still twinkled in the corner. Mr. Gomez wore his cook's whites and Chinese slippers and sometimes sported a cowboy hat, a present from Kay. Depending on his mood, there would be cereal, pancakes, even cheese omelets.

Then what became known as "the March of Archaeology" would proceed down the village's main street. Juris not-totally-awake students led the way, laden with buckets, notebooks, and surveying gear. Next came our volunteers, some of whom had driven eight hundred miles across the desert from Muscat to help out. The rear was brought up by our three Baluchis and their wheelbarrows. At the end of Shisur's main streetâall of three housesâthe March would turn left and soon arrive at the ruins, where the group dispersed to dig, screen, and take notes.