The Road to Berlin (48 page)

Read The Road to Berlin Online

Authors: John Erickson

Tags: #History, #Europe, #Former Soviet Republics, #Military, #World War II

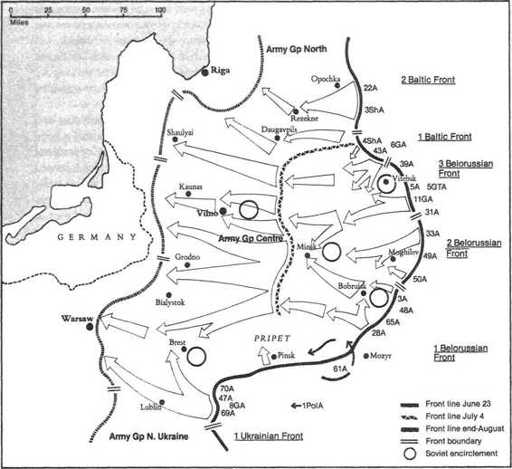

Zakharov’s 2nd Belorussian Front, attacking with 49th Army east of Moghilev, was already grinding through Fourth Army’s defences; the left flank of Fourth Army had to be pulled back to maintain contact with Third

Panzer’s

right, which was being pushed away from Bogushevsk. After three days of dragging battle, on 26 June, forward units of 49th Army crossed the Dnieper and established bridgeheads north of Moghilev; General von Tippelskirch, commander of Fourth Army, in a personal decision that flew in the face of all the ‘stand fast’ instructions emanating from Hitler, was already pulling his army away from the Dnieper. To rush heavy weapons over the broad Dnieper, the 92nd Soviet bridging battalion moved up its equipment quickly on lorries, laying down two bridges—30-ton and 16-ton—under heavy German fire. By noon on 27 June Soviet sappers had the bridges in position; tanks and artillery moved into the Soviet bridgehead

which swelled to some fifteen miles in depth. In the wake of 49th Army came Boldin’s 50th, and together on 28 June these two armies stormed Moghilev from the north and from the south-east, a bloody assault which left the Soviet armies reeling with their casualties.

Chernyakhovskii on 3rd Belorussian Front pushed Oslikovskii’s mobile group on to Senno, moving as fast as possible towards the Berezina. Rotmistrov’s tanks were now fighting their way along the Minsk motor-road and, supported by ground-attack aircraft, they blasted a passage to Tolochino by the evening of 26 June—thereby cutting the German escape route to the west of Orsha. Yet another of the strong-points that Hitler was determined to hold, Orsha, one of the anchors holding the German front in position, fell to 11th Guards and 31st Army on 27 June. Three days after Operation

Bagration

was fully engaged, with all four Soviet fronts in action, Russian armies had made deep penetrations along the entire length of Army Group Centre’s front: three German armies, Third

Panzer

, Fourth Army and Ninth Army, were being sliced away from each other. Soviet operations so far followed the original plan: Bagramyan, having invested Vitebsk, was moving towards Lepel and also preparing to strike with his right-flank armies on Polotsk (thus isolating Army Group Centre from Army Group North, the operational variant Bagramyan had himself suggested to the General Staff): Chernyakhovskii’s first thrust—the attack from the south-west on Vitebsk—had succeeded and now his second, aimed along the ‘Borisov–Minsk axis’, was pushing through the gap torn in the German line and reaching menacingly down Fourth Army’s long flank, all the way to the Berezina: Zakharov had closed in on Moghilev, thereby uprooting Fourth Army.

The situation of Third

Panzer

and Fourth Army was serious: for Ninth Army to the south, it rapidly became catastrophic. On the morning of 24 June Rokossovskii lashed out on his right with his ‘double attack’ on Bobruisk, the operation for which he had risked Stalin’s wrath in arguments over operational planning. The basic aim of the Bobruisk operation was the encirclement of Ninth Army by moving along both banks of the Berezina and then destroying the trapped divisions in or near Bobruisk itself: four armies of 1st Belorussian Front, 3rd and 48th (‘northern group’) and 65th and 28th (‘southern group’) were committed to the attack. Rokossovskii planned the attack on Bobruisk with three powerful columns. Gorbatov’s 3rd Army had orders to attack from the Dnieper bridgehead north of Rogachev in the direction of Bobruisk–Pukhovichi: 48th Army occupied the lower sector, but here marshes and dense woodland forced Rokossovskii to detach most of 48th’s divisions to operate on Gorbatov’s left flank. The two ‘southern group’ armies, Batov’s 65th and Luchinskii’s 28th, had orders to attack along the western bank of the Berezina; two mobile formations, Panov’s 1st Guards Don Tank Corps and Pliev’s ‘cavalry-mechanized group’, attached to 6th and 28th Army respectively, would be used to cut German communications west of Bobruisk.

Marsh, bog, woodland, innumerable small rivers and lakes—above all, the formidable river Drut—lay in profusion across Rokossovskii’s proposed line of advance. The terrain made careful preparation indispensable, though Soviet commanders too often ignored details of this order. This time, however, they had an exacting task-master to supervise them—Marshal Zhukov, who inspected the terrain and the preparations with all commanders. Commanders who displeased him through carelessness or bad planning were ruthlessly sacked, and ‘sacked’ meant the threat of a penal battalion: 44th Guards Division commander was hauled unceremoniously out of his command post by Zhukov and virtually demoted on the spot. Marshal Zhukov bore down on General Batov in merciless fashion, interrogating him on every detail of planning and his proposed operations. In the armoured formations all tanks were equipped with brush and logs to carry them over the soft ground of this marshy region: all tank and self-propelled gun units had sappers attached to them as well as infantry. The tanks moved forward on roads of logs, the infantry carried brush ‘mats’ to ease them over the bogs.

At 0355 hours on the morning of 24 June the guns of 1st Belorussian Front began firing off a two-hour barrage. On the ‘northern’ sector, 3rd and 48th Armies attacked at 0600 hours, followed one hour later by the two on the ‘southern’ sector. During the night, bombers from Rudenko’s 16th Air Army attacked targets in the German rear, but at dawn the weather worsened and closed down massed air operations. It was only later in the day that Rudenko could launch two big bombing raids, though all told 16th Air Army crews flew over 3,000 sorties on 24 June. During the first day the ‘northern group’, 3rd and 48th Armies, made little progress, fighting across swampy land on the Drut. But while it proved to be a dismal day for Gorbatov and Romanenko, Batov got off to a flying start: with 18th Rifle Corps in the lead, supported by ground-attack aircraft, 65th Army broke into the positions held by XLI

Panzer

Corps. At 1400 hours, 18th Corps was already on the line pre-selected to move in the armour. The lead battalions of 1st Guards Tank Corps were standing by to move off: Panov gave the order to advance—the code signal

reka techet

(‘the river is flowing’) transmitted three times—and the first tanks moved forward through the infantry, straightway fighting an action with Ferdinand self-propelled guns, and pushing on into the German lines. The Guards motorized troops, part of Panov’s corps, fought alongside 65th Army infantrymen. And in Luchinskii’s area, 28th Army, the time had come to move in Pliev’s mobile units. By the end of the day both Batov and Luchinskii were five miles inside the positions of XLI

Panzer

Corps on a fifteen mile front, with Panov’s tanks well ahead and closing on Knyshevicha. For a few hours the Soviet and German commands had an inverted image of the battle. Grievously dissatisfied with the ‘northern’ attack, Marshal Zhukov sent his own

Stavka

‘assistants’ to take over the direction of Romanenko’s 48th Army and Urbanovich’s 41st Corps with 3rd Army—‘bad handling of troops’ was what Zhukov reported to Stalin. General Jordan at Ninth Army, however, judged this northerly attack directed against 35th Corps

on the Drut to be the most serious threat and decided to commit his reserve, 20th

Panzer

Division, to a counter-attack. Late in the day—too late as it proved—Ninth Army commander suddenly realized the proportion of Soviet success in the south against XLI

Panzer

Corps, south of the Berezina; 20th

Panzer

received orders to switch southward and counter-attack the Russian armour now piling in, but this diversion cost valuable time.

On the second day of the offensive the ‘northern group’ outflanked Zhlobin to the north, the ‘southern group’ took Parichi and pressed on to the river Ptich at Glutsk. South of the Berezina, Soviet columns cut the railway line leading from Bobruisk. The counter-attack finally launched by 20th

Panzer

into the Russian flank in the south brought no improvement whatsoever. Hauling their guns over the swamps, shoving lorries along clogged roads, building log roads to speed the tanks or picking their way through clumps of forests, Soviet units continued to push on west and north-west, slicing through the road links running out of Bobruisk to the west one by one. Late on 25 June the German command had no very firm picture of what was happening on the northern boundary between Fourth and Ninth Armies, but the growing pressure on Ninth Army placed Fourth Army in a dangerous position; Hitler finally permitted General von Tippelskirch to pull back to the Dnieper, the decision Tippelskirch had already taken for himself and his men, pulling the army out of the most imminent danger and starting a fighting retreat to the Berezina. To the north Third

Panzer

slowly collapsed and to the south Ninth Army had already begun to disintegrate; Fourth Army could be buried alive amidst this gathering landslide of battered corps and divisions.

Throughout the next twenty-four hours Pliev’s mobile group and Panov’s tanks struck on towards the north-west in the direction of Bobruisk, hacking at Ninth Army’s rearward communications. On the evening of 26 June, though insisting that Moghilev must be held, Hitler was prepared to allow Fourth Army to fall back on the Berezina and Ninth Army to pull into the ‘Bobruisk bridgehead’: Bobruisk finally proved to be the grave of Ninth Army, though Hitler insisted that it must be held to anchor the Berezina line. Gorbatov’s 3rd Army, backed by powerful artillery support and with a tank corps (the 9th) at its side, rammed its way to the Berezina and seized several bridgeheads on the western bank, to the north-east of Bobruisk: with the bridges over the river now captured or shelled by Russian guns, units of 35th Corps and XLI

Panzer

Corps trying to pull into Bobruisk were pinned on the eastern bank. Panov’s tanks, with Batov’s infantrymen in their wake, came striking up from the south-east. The trap closed on five German divisions in Bobruisk itself and to the south-east.

In an attempt to clear the bridges over the Berezina, 20th

Panzer

Division was smashed to pieces; 35th Corps struggled frantically to free itself by attempting to break out to the north where the Russian ‘ring’ was at its loosest, held mainly by 9th Tank Corps. Rokossovskii ordered three armies, 3rd, 48th and 65th, to hold the 40,000 Germans so far entrapped in the Bobruisk ‘cauldron’, while

the fast units made for Slutsk to the west and for Osipovichi–Pukhovichi (on the road to Minsk). South-east of Bobruisk, between the main highway and Berezina, units of XLI

Panzer

and 35th Corps were stranded in the spreading woods, cut off from Bobruisk by Gorbatov, prodded from the south by Romanenko’s 48th Army and now shelled from the western bank of the Berezina by Batov’s guns. Inside Bobruisk the German garrison, swelled with troops who had managed to get back to the town, set up strong-points, laid barricades and positioned

AA

guns to fire at ground targets in readiness for the Russian assault. Towards evening on 27 June units of 35th Corps, with 150 tanks and self-propelled guns leading off, tried once again to blast their way through the Russian trap to the north, but Gorbatov’s men turned the German column back. The troops still locked inside the ring set about destroying vehicles, equipment and stores, the smoke from the burning dumps billowing into the evening sky. Taking this as an indication that a major break-out was imminent, Rokossovskii ordered Rudenko to send in a mass of bombers from 16th Air Army: in just under an hour 526 planes—400 of them bombers—dropped 12,000 bombs across the few square miles in which the German corps were encased, a merciless aerial lashing which tore men and machines to pieces, ripping up the ground, smashing the remaining tanks and assault-guns with rocket attacks.

In the morning Romanenko’s men moved into the forest to engage the survivors, who finally gave up the struggle by the evening: 6,000 men marched into captivity. The storming of Bobruisk began on the afternoon of 27 June with a Soviet tank attack which the defenders beat off. At dawn the next day, units of 48th Army crossed the Berezina and fought their way through the eastern outskirts of Bobruisk, while a German battle group 5,000 strong from XLI

Panzer

Corps, the commanding general at their head, battled to break-out on the northern edge of Bobruisk, only to be met by Gorbatov’s troops. The final Soviet assault went in at 10 am on 29 June, Batov’s men cooperating with Romanenko’s units to clear the blazing town: further to the west Soviet mobile columns had already taken Osipovichi, the junction on the railway line to Minsk.

One week after the opening of the Soviet offensive, the first phase of the battle for Belorussia ended; with the fall of Vitebsk, Orsha, Moghilev and Bobruisk, the German defensive system of the central sector of the Soviet–German front had cracked wide open. The three German armies had lost over 130,000 men killed, 66,000 taken prisoner (almost half of them—32,000—falling to Rokossovskii), 900 tanks and thousands of motor vehicles. In the north, Third

Panzer

was left with only one badly weakened infantry corps, in the centre Fourth Army stood daily in greater danger of being cut off in its long retreat to Minsk and to the south Ninth Army could count only three or four dispersed and battered divisions from the wreckage of its corps. The whole Russian attack had been ruthlessly pressed home and on some sectors mounted with real fury; though

Soviet tactics had visibly improved, and co-ordination vastly bettered upon past performance, the cost in human life was appalling. General Bagramyan confessed himself shaken to the core by the losses incurred by his front: Zakharov’s 2nd Belorussian Front, victor in the bloody immolation of Moghilev, was forced to refit and recoup.