The Road to Berlin (124 page)

Read The Road to Berlin Online

Authors: John Erickson

Tags: #History, #Europe, #Former Soviet Republics, #Military, #World War II

Rybalko’s tanks, reinforced by heavy artillery rushed up from the Spremberg area, crossed the Nuthe canal and continued their advance from the Mitten-walde–Zossen sector, with 9th Mechanized Corps in the lead and closing on the Berlin ring-road. Towards the evening of 22 April 9th Mechanized, accompanied by the 61st Rifle Division (28th Army), broke into the southern suburbs of Marienfelde and Lankwitz; elements of the corps also drew up to the Teltow canal, only to be met by heavy fire from the northern bank. By the evening of 22 April the tanks of 3rd Guards were only about seven miles from Chuikov’s 8th Guards, fighting in the south-eastern suburbs. Meanwhile Marshal Koniev ordered Rybalko to prepare the assault of the Teltow canal, a water barrier lined with factories whose reinforced concrete walls formed an unbroken rampart well suited to defence. The Germans had already blown the bridges, leaving the Soviet commanders no option but to force a crossing and to mass artillery—3,000 guns,

SP

guns and mortars—on a narrow sector, in addition to all the direct-fire guns that formation commanders could lay their hands on. In this fashion Koniev intended to smash his way straight into the heart of Berlin.

The whole gigantic trap was almost sprung. Lelyushenko was a mere twenty miles from Perkhorovich driving down from the north; Rybalko would shortly make contact with Chuikov and Katukov, only a few miles separating the two fronts in the southern suburbs of Berlin. During the course of 22 April Gordov’s 3rd Guards Army finally took Cottbus and completely bottled up the German ‘Frankfurt-Guben group’ from the south, while Pukhov’s 13th and Zhadov’s 5th Guards Army cut the German escape route to the Elbe, the junction between the two armies being sealed by 4th Guards Tank Corps. Luchinskii continued his advance towards Berlin, pushing 128th Corps towards the Teltow canal and Rybalko’s 3rd Guards Tank Army, while the 152nd Rifle Division moving towards Mittenwalde held off a small group of German troops from the Frankfurt-Guben group as they tried to break towards Berlin; Luchinskii also deployed one corps in the Barut area as added insurance against any break-out by the Frankfurt-Guben group. Chuikov’s advance into the south-eastern suburbs and Rybalko’s thrust with 28th Army into the southern suburbs presented the possibility of splitting the Berlin garrison into two separate entities, while the main body of Ninth Army had also been encircled and might be kept isolated in the woods to the south-east of Berlin. The distance between the outer and inner lines of encirclement was some fifty miles to the west and a little more than thirty miles in the south.

Both Hitler and Stalin bent over their maps at this critical juncture in the battle for Berlin, though the contrast in their approach to reality was its own cruel commentary—Hitler manipulating phantom forces and decimated divisions, Stalin and the

Stavka

calmly supervising the movement of score upon score of divisions, massed batteries of artillery and huge columns of tanks. On 22 April

Hitler suffered a total nervous collapse, raving at what he conceived to be more treachery. His best hope had centred on

SS

General Steiner, whose ‘Army Group’ would attack from its positions near Eberswalde in a southerly direction, cutting off Zhukov’s offensive on Berlin and slicing right into his northern flank. To swell this force Hitler ordered Göring’s private army to be placed under Steiner’s command and the bulk of the

Luftwaffe

’s ground staff. But Steiner could neither command the means nor summon the will to attack. The explosion came not on the battle lines but in the

Führerbunker

on the afternoon of 22 April, when a deranged and hysterical Hitler learned that Steiner had not attacked, in spite of the soothing reassurance of the

SS

. To the amazement of his entourage Hitler declared the war lost and his own life forfeit, his fate being to remain in Berlin and if needs be end his life with a pistol shot. He refused adamantly to alter his decision to remain in Berlin and announced his intention to broadcast the fact; the entreaties of his intimates made no impression. It was left to Jodl to point out that a dead

Führer

would leave the German army leaderless and even as the thudding of Soviet shells reverberated through the bunker Jodl pointed to some remaining reserves—Schörner’s army group and especially Wenck’s Twelfth Army, which could be turned about from the Elbe and directed eastwards towards Potsdam, there to link up with Busse’s Ninth Army. In addition, Steiner and von Manteuffel could strike towards Berlin from the north. In the early hours of 23 April Field-Marshal Keitel reached Wenck’s

HQ

and ordered him, amidst much brandishing of a field-marshal’s baton, to abandon his positions on the Elbe and drive towards Jüterborg and Potsdam.

Shortly before 1 am on 23 April—a mere fifteen minutes or so before Keitel reached Wenck’s

HQ

in the Weisenburg forest south-west of Berlin—Stalin issued a definitive order setting the boundary line between 1st Belorussian and 1st Ukrainian Fronts, Stavka Directive No. 11074, classified secret and timed for 0045 hours 23 April. Stalin’s cut was deep and decisive. The revised frontal boundary line ran from Lübben, on to Teupitz, Mittenwalde, Mariendorf and thence to the Anhalter Station in Berlin—a line which sliced right through Berlin and placed Marshal Koniev’s 1st Ukrainian Front just 150 yards to the west of the

Reichstag

, thus disbarring him from any attempt to seize the outstanding prize which would signify the capture of Berlin and the defeat of the

Reich

. The palm was to go to Zhukov, who might wear the title of ‘conqueror of Berlin’, exactly as Stalin had insisted he should as long ago as November 1944. The new boundary line was to come into effect from 0600 hours on 23 April.

Koniev had already flung almost the full weight of his right flank into the battle for the south-western and southern suburbs of Berlin, while his centre and left-flank armies pushed on westwards and to the Elbe. Rybalko’s 3rd Guards Tank Army was drawn up on the banks of the Teltow canal, waiting for the arrival of the heavy guns and carrying out a thorough reconnaissance. Soviet officers could see lines of trenches, pill-boxes and tanks buried in the ground, bridges clearly mined or already blown; but since there was little attempt to camouflage or conceal these defences, guns could be brought right up to the forward positions and simply blast away, with aimed fire reserved for certain street crossings, gardens and specific buildings. This concentration of Soviet fire-power beggared even the imagination of Koniev—650 guns per kilometre of front for the assault, 55 minutes of massed fire timed for 0620 hours on 24 April and supporting the three corps committed to the attack. No less than 1,420 guns were brought up to this sector with 400 (including 122mm pieces) sited for firing over open sights. The staggered hour for opening the barrage—0620 hours, rather than the orthodox clockwork precision of 0600 or 0700 hours—was designed to throw the German defenders off balance.

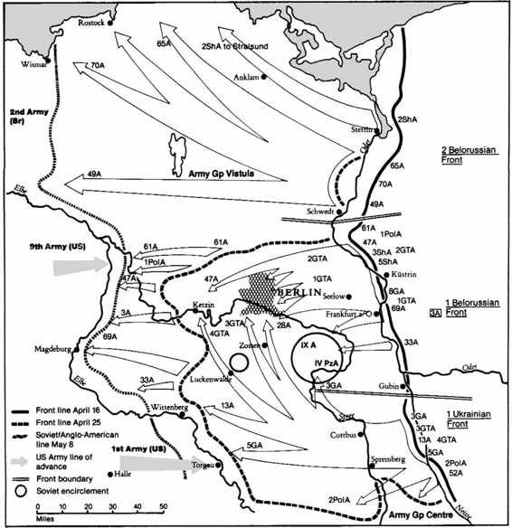

Map 15

The Berlin operation, 16 April-8 May 1945

Rybalko also received orders to take the greatest care with his right flank, in order to effect a smooth junction with Katukov’s 1st Guards Tank Army from 1st Belorussian Front; 3rd Guards would now advance towards Buckow and render assistance as 1st Guards made its crossing of the river Dahme. Already liaison officers had made contact between the two tank armies, and at 0125 hours on 23 April Koniev ordered Rybalko to use 9th Mechanized Corps to drive on Buckow and link up with Katukov’s tanks, facing the barrier of the Spree. Rybalko accordingly detached 70th and 71st Mechanized Brigades to drive up to 1st Guards Tank Army and secure the requisite street crossings east of Marienfelde. During the course of 23 April Lelyushenko with 4th Guards tanks pressed on towards Potsdam, narrowing the gap with each hour between the two fronts—1st Belorussian and 1st Ukrainian—in order to close the outer encirclement, the gap now being only about fifteen miles; 6th Guards Mechanized Corps continued its push towards Brandenburg, covering fifteen miles in the course of 23 April and completely smashing up the

Friederich Ludwig Jahn

division in the process.

Marshal Zhukov meanwhile attended to the execution of the

Stavka’s

orders. He pushed 47th Army on to Spandau, ordering one division to break through with a brigade from 9th Guards Mechanized Corps and drive towards Potsdam in order to link up with Lelyushenko’s tank army. Chuikov with 8th Guards and Katukov’s tank army received categorical orders to force the Spree and not later than 24 April drive into the area of Tempelhof, Steglitz and Marienfelde; Bogdanov’s 2nd Guards would simultaneously attack towards Charlottenburg in the western districts of Berlin. Impatient as ever and determined to crack the German resistance, Zhukov had already ordered his formation commanders on 22 April to organize round-the-clock operations with assault squads fighting by day and by night and with tanks included in the assault companies. To supplement available tank strength for street fighting, during the night of 23 April Zhukov regrouped some of the armoured formations, subordinating 9th Tank Corps to 3rd Shock Army, 11th Tank Corps to 5th Shock Army, and a tank brigade to Chuikov’s 8th Guards. Perkhorovich’s 47th Army with 9th Guards Tank Corps continued its northerly sweep, with two corps—125th and 129th—across the Havel and investing Tegel. Kuznetsov’s 3rd Shock with two armoured corps (1st Mechanized and 12th Guards Tank Corps) cut its way into the northern and north-eastern suburbs, clearing several apartment blocks and reaching the Wittenau–Lichtenberg railway line. Berzarin’s 5th Shock drew up to the Spree and managed to win some footholds on the western bank, ready to make a full assault crossing west of Karlshorst.

At long last Chuikov’s 8th Guards enjoyed a stroke of luck. Moving up to the Spree and the Dahme, units of two corps (28th and 29th Guards Corps) found a variety of boats and barges, even motorboats, on the eastern bank and promptly pressed them into Red Army service. The sailors of the Dnieper Flotilla were also much to the fore, managing to ferry forward elements of 9th Guards Rifle Corps (5th Shock Army) across the Spree. Chuikov smashed down the resistance in his area and taking the Wuhlheide moved his corps across the Spree, pushing on to Adlershof in the afternoon. By the evening of 23 April one corps (28th Rifle Corps) was fighting in Alt-Glieicke and Bohnsdorf. Chuikov was now in a good position to link up with Rybalko’s tanks also drawing up to this south-eastern sector.

There was every reason for the salutes of gunfire in Moscow on the evening of 23 April, salvoes celebrating the successes of both the 1st Belorussian and the 1st Ukrainian Fronts. The great link-up was about to take place, with 8th Guards and 1st Guards Tank Army making contact with Rybalko’s 3rd Guards Tank Army and Luchinskii’s 28th Army in the south-eastern sector of Berlin. Soviet armies had closed on Berlin from three sides, leaving only three roads open to the west and these were being harried constantly by Soviet aircraft. The net had almost closed on the ‘Frankfurt-Guben group’, with the

Stavka

ordering its rapid liquidation. A gap wavered to the west of Berlin but a rifle division from 47th Army and a tank brigade from 2nd Guards Tank Army were racing to link up with 6th Guards Mechanized Corps from Lelyushenko’s tank army. After days and hours of agonized, bitter fighting the grand plan was about to be consummated. However, the wounds inflicted on the Red Army were deep and they hurt: companies were down to 20–30 men, regiments were fielding only two battalions rather than three, the battalions pressing men into companies consisting of a mere fifty men. The Russians could only bury their dead in gardens and sundry open spaces, all the while counting the cost of this massive assault.

Much to his dismay Col.-Gen. Chuikov received a telephone call on the evening of 24 April from Marshal Zhukov, who peremptorily demanded to know the source of the news of Koniev’s advance into Berlin—who had reported this? Taken aback, Chuikov replied that units on the left flank of 28th Rifle Corps had made contact at 0600 hours in the area of the Schonefeld aerodrome with Rybalko’s tanks from 3rd Guards, contact duly confirmed by the corps commander himself, General Ryzhov. A querulous and sceptical Zhukov ordered Chuikov to send out ‘reliable staff officers’ and find out which units from 1st Ukrainian were in Berlin and what their orders were. Chuikov dispatched three officers, but in a matter of hours Rybalko himself turned up at Chuikov’s command post and telephoned Zhukov—proof positive of the presence of 1st Ukrainian Front, if Zhukov wanted proof. Not only had the link-up taken place between the two fronts inside Berlin but close operational liaison brought left-flank units of 28th

Rifle Corps (8th Guards Army) to the Teltow canal and into the districts of Britz, Buckow and Rudow. Units of 29th Rifle Corps meanwhile invested Johannisthal and the aerodrome at Adlershof.

While this encircling knot was drawn tighter and tighter, pulling on the inner noose draped round Ninth Army, the outer ring was closing fast: Colonel Turkin’s 35th Guards Mechanized Brigade, the lead element in 8th Mechanized Corps from Lelyushenko’s 4th Guards Tank Army, raced towards the north-west from Potsdam in the direction of Ketzin. At noon on 25 April, here at Ketzin, the two outer encircling wings from 1st Ukrainian and 1st Belorussian Fronts finally linked up. This junction was effected by 6th Guards Mechanized Corps, from 1st Ukrainian Front, and the 328th Rifle Division from General Poznyak’s 77th Rifle Corps (47th Army) and 65th Guards Tank Brigade (2nd Guards Tank Army) from 1st Belorussian Front. Intent on isolating and then chopping up the Berlin defences, the Soviet command could now count on an encirclement line manned by at least nine armies—47th, 3rd and 5th Shock, 8th Guards, elements of 28th Army and four tank armies (1st, 2nd, 3rd and 4th Guards); in the wooded country to the south-east of Berlin, the ‘Frankfurt-Guben group’ was hemmed in by another five armies—3rd, 69th, 33rd, 3rd Guards and more units from 28th Army.