The Rising Tide: A Novel of World War II (52 page)

Read The Rising Tide: A Novel of World War II Online

Authors: Jeff Shaara

Tags: #Fiction, #Historical, #War & Military, #Action & Adventure

Patton stood silently, watched as Alexander crossed his arms, rocked slowly, the frown settling into a hard scowl. “Monty, I should like to hear your plan, if it’s all right with you.”

Montgomery shrugged. “We’ve been over the details. George sees things the same way I do. I expect no difficulties—”

“

Tell me your plan

.”

It was the first time Patton had heard Alexander raise his voice, cold silence now holding them all still.

Montgomery seemed to pause, his voice low, calm. “Certainly, Alex.”

Montgomery spoke for long minutes, others joining in, the men around them offering information, filling in details, Smith contributing as well. The details did not change the overall plan, Patton realizing that his every suggestion had been accepted without argument, which was more than simply unusual. As the discussion continued, Patton mostly watched and listened, could clearly see Alexander’s anger. He felt suddenly giddy, was now overjoyed that Beetle Smith was there to witness this scene, to pass the word on to Eisenhower. Patton had rarely been the innocent bystander, the one man in the crowd who wasn’t the source of the friction.

After long minutes in the sun beside Montgomery’s car, after the details had been sketched and analyzed, Alexander silenced them all, looked at Patton. “What of it, General? This seems like a plan that offers the Americans an opportunity to share the spoils, so to speak. Ike has been most insistent about that, as have you. Is this acceptable to you?”

“Yes. Quite acceptable. It won’t take a month, though.”

Alexander glanced quickly toward Montgomery. “A bold statement, George. Victory favors the bold, certainly. But I won’t hold you to it. I must note one thing. This level of cooperation must certainly demonstrate that my command, that Fifteenth Army Group, is completely Allied in mind. I favor neither army. Ike has been assured of this many times. I hope this satisfies you on that point.”

Patton nodded slowly. “It certainly seems that way.”

“Very well. I will return to my headquarters. You gentlemen have my perfect confidence. Let’s get the job done, shall we?”

Alexander moved away quickly, and Patton was surprised to see him board his plane. Alexander’s staff was surprised as well, the men scrambling to catch up, the pilots still in the cockpit, as surprised as their passengers. Patton looked out toward his own plane, the crew seated in the shadow of the wing, the men watching for his signal, the order that it was time to go. But Patton wasn’t sure what was happening now, thought of lunch, the suggestion offered by the British colonel. He turned to Montgomery, who motioned to his aide, the young captain rolling up the map.

Montgomery said, “I told you not to worry! Alex knows I have things well in hand here. As he said, it’s up to us to get the job done.” Montgomery moved around the car, the aide rushing to open the door. Montgomery stopped now, reached into his pocket, pulled out a small cigarette lighter. He held it out toward Patton, said, “Please accept this gift, George. Token of my esteem, and all that. We get to Messina, I’ll have a formal celebration, dinner, whatnot. You bring this along, we’ll light each other’s cigars, eh?”

Patton fingered the lighter, watched as Montgomery climbed into the car. Around him, the officers were dispersing, each man with his own job to do, no one seeming to think about lunch.

The car pulled away, and Smith was there now, said, “So, what did Monty give you?”

Patton held up the lighter, examined it for a moment, flicked the small wheel, saw a faint flicker of spark. “Probably cost about a nickel. Someone must have given him a box of the damned things.”

Smith said nothing, and Patton began to walk now, moving across the tarmac, Smith calling out, “I’ll tell Ike about this. All of it. We’re behind you, George.”

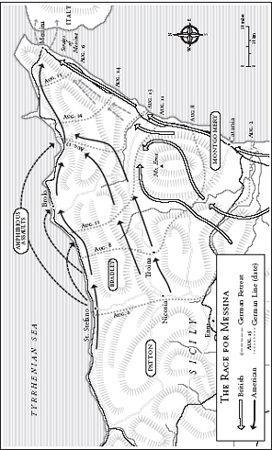

Patton raised a hand, a brief wave, moved toward the plane, his mind on the maps, the two roads that led to Messina, Montgomery’s boast, his plan for a dinner, lighting each other’s cigar. Where will we do that, Monty? In my headquarters or yours? I guess that might depend on who gets to Messina first.

37. KESSELRING

ROME

JULY 25, 1943

I

t was late, the city darkened by rumors of Allied bombing raids. It had been a struggle to convince anyone in the Italian government that the city was under threat, but Kesselring had heard too many radio intercepts and too many intelligence reports, had to believe that the Allies were giving strong consideration to violating the informal agreements that Rome should be spared. It is our fault, he thought. We have put this place at risk. It is one thing to man the nearby airfields and ring the city with troop encampments, but now…the war has come too close. This city could become a battlefield. Would we bomb it if

they

were here? He shook his head, knew the answer to that already.

He stared into the darkened streets, saw cars with headlights, a direct violation of the blackout order. It had been that way since the lights had gone out, so many of the Italians still oblivious to the war. He marveled at that, thought, they are a unique race, so enraptured by their history that they are incapable of seeing the present. We are so different from that. So much of the Führer’s strength comes from using the past as a tool, inspiring Germany against those who have struck her down, who would keep her down still. It is an imperfect strategy, of course. So often, Hitler has chosen to look away from things as they are, dreaming of a world as he wishes it to be. That is a luxury a soldier does not have.

He backed away from the window, pulled the black shroud over the tall glass, moved to his desk, lit the small lamp. Who is right, after all? A soldier cannot think on that either. We do not weigh the value of our cause, we simply fight to preserve it. We might certainly be fighting now just to preserve ourselves. He reached for the bottle of brandy, pulled the cork, held the bottle to his nose, breathed in the sharp, flowery warmth. The small glass snifter sat empty on the desk, and he poured a small amount from the bottle, thought, not too much. I don’t need any headaches in the morning. He turned toward the curtain, thought, a warm night, no breeze. I should take a walk. I should truly enjoy that. No, it’s foolishness to think of that. Far too late. Much to do tomorrow. There is always much to do. I must see the reports, I must know what the enemy is doing. I should send for Hube, meet with him face-to-face. We are fortunate to have such a man in Sicily, a man I can depend on. He thought of Rommel, had once felt the same way about him. Rommel is in the Führer’s lap now, and it must be killing him.

Rommel had spent six weeks in the luxury of Semmering, recovering from his illness, and Hitler had patiently waited for his return, still regarded the Desert Fox with a biased affection that boiled the blood of the senior German staff. For some weeks Rommel had stayed close to Hitler, serving as an adviser, in reality, a man with nothing to do. But then, German intelligence had become convinced that the Allies would attempt an invasion of Greece, to drive a wedge west of the beleaguered German army that was still embroiled in a massive campaign against the Russians. Rommel had been chosen to lead the forces that would presumably confront the Allies when they came ashore in Salonika, the Greek peninsula that jutted into the Aegean Sea, the most logical place for such a landing.

Rommel is there now, he thought, pulling men together for an invasion that even Rommel knows will never come. No matter, he will do the job. He will live out the perverted joke, poring over intelligence reports from men who still believe the invasion of Sicily is a feint. There are still men in Berlin who believe the Allies have so many resources, they can mount operations anywhere they choose. Kesselring smiled through his gloom, thought of Hitler. Ah, but none of that matters to you as much as holding Rommel close to you, so you can keep one hand on his shoulder. Greece is better than Africa. The Führer knows what I know, that Rommel cannot always be trusted to do what we wish him to do. And if he were not in Greece, then he would be here. What would he do in Sicily? How would he deal with Montgomery this time? We will never know the answer to that. The Italians will not have him. It is my security, the one thing that keeps me in good graces with all those nattering generals in Berlin. No one else can get along with the Italians.

He sniffed the brandy, swirled it in the glass, took a small sip. How much longer will that matter? How much longer will the Italians allow us to fight this war on their soil? Despite what Mussolini tells his ministers, the Italian army is crumbling, falling apart, and that will only get worse. The only force holding the enemy back in Sicily is German. Hans Hube is the best we have right now, perhaps even better than Rommel. We can no longer dream of driving the enemy into the sea. There is no victory to be had in Sicily, there is only survival. Rommel understood that in Tunisia, tried so hard to convince all of us to withdraw and save the army. But Berlin would not yet hear that kind of talk, and Rommel was too noisy about it, paraded his cause with heavy boots, was never a diplomat about anything. He believed he was fighting the war himself, that if it was not Rommel’s way, it was failure. It didn’t matter that he might be right. He made enemies.

Kesselring shook his head. He has one friend though. I do not understand why Hitler loves him so. If I had disobeyed so many orders, I would have been shot.

He finished the brandy, thought, they will come. There will be bombs in this place, and the Italians will be outraged. The Führer must believe that will help us, inflame the Italians to be better fighters, to drive the Allies off their soil. He shook his head, moved toward the lamp. No, it will only make them quit. These people are not the British. They do not have that kind of resolve, will not watch their country destroyed and vow to fight on.

He paused at the lamp, was not yet ready for the dark, thought, so many errors, so many disastrous errors of judgment and strategy and planning. We are supposed to learn from our mistakes, but there can be no lessons when the mistakes never end.

There was a soft knock at the door, and Kesselring said, “Yes. Enter.”

The door swung open, and he saw Westphal, Rommel’s former aide, now Kesselring’s chief of staff.

“Sir, my apologies. But it is most urgent!”

Kesselring tilted his head, his ear trained to hear the sound of bombs, but there was only silence. “What has happened?”

“Word has come from the palace, sir, directly from the king himself. Herr Mussolini has been deposed by the Fascist Grand Council. He has been placed under arrest.”

Kesselring leaned against the desk, felt the air leave him. “But I spoke to him yesterday. He was fully confident in their loyalty. There was no hint that anything was wrong.”

Westphal said nothing.

Kesselring stood straight again. “Just like that? Tonight? Without warning?”

There was no answer to his question, and he stared past Westphal, tried to shuffle through the names and faces, all the men who would scramble to the top, the fights that were bound to erupt. Who had remained loyal to Mussolini, and who had betrayed him? It has to matter. Who is in command now? He thought of the king, the fragile old man, Victor Emmanuel. It had been a tenuous relationship between the monarchy and Mussolini, and though Mussolini had taken the power, he had wisely left the king to his throne, knowing that the Italian people loved the old man and respected his influence.

“Send word to the king. I must meet with him as soon as possible. This changes our situation considerably.”

“Right away, sir! Heil Hitler!”

Westphal was gone, and Kesselring felt the warmth from the brandy, reached for the bottle again, pulled the cork, said aloud, “Yes. This changes our situation considerably.”

G

eneral Hans Hube was a veteran of the First World War, had lost his right arm at Verdun, but unlike so many who carried horrific wounds, he had lost none of his spirit for the fight, had continued what was now a lengthy career in the army. Hube had served well at the Russian front, surviving the disaster of Stalingrad, while catching Hitler’s eye as one of the premier fighting generals in the German army. Now, he commanded the German forces in Sicily and, in that theater, was subordinate only to Kesselring. Hube had gained the command not by his own ambitions, but by a strong recommendation from Rommel, who had convinced Hitler that Hube was the right man to turn the tide against the power of the Allied invasion. Kesselring gave little credence to Rommel’s reasons for supporting Hube, had even wondered if Rommel had suggested Hube for the command because he thought Hube would fail. Kesselring could not avoid speculating that Rommel’s separation from the front lines was more painful to him than the illness he had carried home from the desert. If Rommel truly missed life among the tanks, Kesselring had to believe that Rommel might be tempted to engineer a disaster, just so Rommel could ride south and save the day. But any doubts Kesselring had about Hube had been put to rest. In the two weeks since Hube’s arrival, Kesselring had seen none of Rommel’s defeatism and rebellious independence. Even better, Hube seemed completely free of the delusional fantasizing that surrounded Hitler and his staff. Hube understood exactly what was happening in Sicily, what his role was, and he was going about the job with perfect efficiency.

ROME—JULY 28, 1943

“I have met with King Victor Emmanuel. Fortunately, he and I have always had a cordial relationship. The king informs me that Pietro Badoglio is now the head of the government and has assumed command of all Italian armed forces.”

Hube said, “Can we trust him?”

Kesselring shrugged. “He is the king. He insists he is our ally still and will remain so, and that Badoglio will continue to cooperate with us.”

“Do you believe him?”

Kesselring smiled. “It matters little what I believe. It matters that we continue to do our jobs. I am quite certain that the Führer is devoting a great deal of energy to the reappraisal of our relationship with our ally. However, until I am notified otherwise, my role here has not changed. Neither has yours.”

“Certainly, sir.”

Kesselring said nothing for a long moment, Hube content to wait for whatever came next.

“You are a patient man, Hans. I have not enjoyed such luxury in the past.”

“I don’t know what you refer to, sir.”

“Never mind. I am being indiscreet. Tell me about

your

Italians.”

Hube seemed to energize, the subject turning to his own concerns. “I do not feel there has been any significant change. Since my arrival, I have been somewhat careful not to place any serious reliance upon General Guzzoni, and I have not considered the Italian army to be an asset to my planning. I have no plans to deploy them in any area requiring great skill or sacrifice. In any position where there is danger of a significant enemy assault, our own people have been used.”

Kesselring smiled again, thought, I have heard this sort of thing before. “What of the officers?”

Hube shook his head. “The Italian officers do not seem affected by the arrest of Mussolini, but of course, that may change. As you know, some of the senior commanders known to be especially loyal to Mussolini have been replaced. Those changes are the concern of General Guzzoni. They are of no consequence to me.”

Kesselring tapped his fingers on the desk, thought a moment. “I wish you to continue with your overall strategy of gradual withdrawal. But you should know that once we are out of Sicily, all of Italy might become a hostile area. No orders have come to me from Berlin, and I suspect it is because I am seen as a friend to the Italians. But already there is troop movement to the north, and I have received reports that our forces are strengthening the mountain passes along the Austrian border. Despite what the king tells me, I do not believe the Italian government is long for this war. It is in the air here, in every hushed conversation. The alliance between our country and Italy was made possible by the Führer’s friendship with Mussolini, and now that Mussolini is gone, I have seen indications from the Italian politicians that our troops are being seen more as an army of occupation. I am quite certain that the Führer will not allow Italy to slip away, but I fear they already have.” Kesselring paused. “I am far more concerned with preserving German troops and equipment than I am in holding on to Sicily.”

“Yes, sir, I have understood that from the beginning.”

“The Führer certainly understands that a war of attrition will eventually cost us more than anything we might gain. There is far more value to us in delaying any efforts the Allies might make toward occupying Italy. Any such move would likely drive the Italians out of this war and might possibly cause them to change their allegiances altogether. I have no doubt that it was always the enemy’s intention to use Sicily as a launching ground for an assault on the Italian mainland. Churchill speaks of it openly, and I do not believe he is clever enough to offer that as some sort of ruse. The catastrophe that occurred in Tunisia must not be repeated on Sicily. Your forces are needed for the next campaign, and I will not lose you to an Allied prison camp. To that end, you will employ a precise plan of withdrawal and maintain the port of Messina as your primary point of evacuation. It must be done carefully and with severe penalty to the enemy. The success of this evacuation will rely on your ability to make the enemy pay dearly for what he will believe are his successes. I am confident that Montgomery will oblige us, as he did in Africa. He is a methodical man, slow to take advantage of opportunity. That will be extremely helpful to you. I do not know this man Patton. He could be far more dangerous, and you must teach him to use caution as well.”

“Sir, there is risk that the evacuation itself could be disastrous. The Allied naval and air power—”

“There are advantages the enemy cannot counter, General. The straits are too narrow for warships to maneuver effectively. The crossings can be made at night and, with only two miles to span, can be accomplished quickly. I will order every available antiaircraft and flak battery transferred to the Messina area. We will employ them on both sides of the straits. Any Allied planes seeking to interrupt our plans will be met with a wall of fire such as they have never seen before.”