The Rising Tide: A Novel of World War II (34 page)

Read The Rising Tide: A Novel of World War II Online

Authors: Jeff Shaara

Tags: #Fiction, #Historical, #War & Military, #Action & Adventure

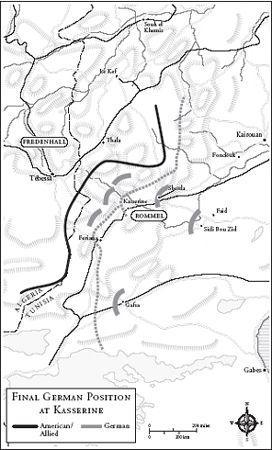

KASSERINE, TUNISIA—FEBRUARY 20, 1943

It was early, just after seven, the fights resuming all across the western side of the mountains. But the Germans had most of the higher ground, the pass itself, were gathering strength, reorganizing, assessing their losses, preparing to continue Rommel’s surge along the roads beyond. In the town, Arabs offered him baskets of food, a hasty breakfast prepared by local civilians, men with toothy smiles and dirty hands. He had been polite, but had no interest in breakfast, and no patience for diplomacy. He had come to Afrika Korps headquarters to speak to Heinz Ziegler, yet another commander of an army that had too many new faces.

“What is happening at Sbiba, General?”

Ziegler ignored the maps, and Rommel thought, refreshing, a man who holds the facts in his head.

“The Twenty-first has been slowed by a stout defense, sir. The British have been meticulous with their mines and are making a strong fight. We made mistakes, sir. I have done all I can to correct them.”

“I know, General. I wanted to hear that from you. I wanted to know you understood your error. We are no longer in the desert. These hills…we might as well be fighting in the Alps. You don’t just march into the pass, you must send your men up the mountains as well.”

Ziegler seemed to energize. “Yes, sir. And we have been successful, sir.”

Rommel thought a moment, could not avoid the maps, moved that way, a young lieutenant stepping aside, the man who moved the pins.

“Are these the latest positions?”

“Yes, sir.”

Rommel stepped closer, tried to focus on the lines, his eyes betraying him. He had suffered from poor vision for some time now, yet one more ailment, one more plague he had to endure. He stepped back, tried to hide the frustration, thought of the plan, the troop positions locked in his memory. He had held the Tenth Panzer Division in reserve, the men who had answered directly to von Arnim. But the opportunity was clear now, the way open to driving the enemy completely away. With Kasserine Pass in German hands, the route was open to Tébessa. Damn them, he thought. They do not see it. Von Arnim has no interest in success. But I will not ignore the opportunity. He can have his prize of Le Kef. I am taking Tébessa.

“General Ziegler, I believe Kasserine is our best opportunity. The Twenty-first surely has matters in hand at Sbiba, so we shall make our greatest effort right here. I will summon the Tenth to Kasserine.”

“Yes, sir, I quite agree.”

Rommel looked back at Ziegler, a young man who had already made his share of mistakes.

“I don’t need you to agree with me, General. Just accomplish your task.”

H

e had driven all along the frontline positions, then back toward the reserves, had watched as the Tenth Panzer Division responded to his orders. Despite the power that rolled past him, Rommel knew that something was wrong, the numbers too low. There was another noticeable absence as well, not just in numbers but in strength. The Tenth held the army’s vastly critical supply of Tiger tanks, and Rommel searched for them, growing more angry along every kilometer. Von Arnim’s promise to send thirty Tigers southward had never been fulfilled. But now, with the Tenth coming forward, all the Tigers should have been there, adding even more to the power of Rommel’s attack. Rommel was furious, ordered his driver toward Afrika Korps headquarters again, knowing the Tenth’s commander, Fritz von Broich, would already be there.

H

e burst through the door, saw Ziegler again, the man jumping to his feet, surprised.

“Where is von Broich?”

“Here, sir.”

Rommel stared at him, von Broich emotionless, sure of himself.

“Where is the rest of your division, General?”

Von Broich did not respond, and Rommel closed the gap between them, put a finger close to the man’s chest.

“Where is the rest of your division, General?”

Von Broich tried to stand tall, a display of bravado, the man quietly aware that he answered only to von Arnim.

“I was specifically ordered to advance with half my force, sir. General von Arnim is concerned that he will require the remainder along his front.”

“Where are the Tigers?”

Von Broich cleared his throat, looked down, and Rommel thought, all right, here comes the lie.

“Sir, General von Arnim has requested that I communicate to you that the Panzer VI tanks are currently undergoing repair.”

“Repair?

All of them?

”

Von Broich did not look at him. “I have been ordered to give you this message, sir.”

Rommel felt a tightness in his chest, his fingers curling into fists. He was breathing heavily, the curses pouring through his brain. I will kill that man.

He fought against the fire, began to feel dizzy, von Broich seeming to waver in front of him. Rommel saw a chair, moved that way, steadied himself, sat slowly, said, “So, this is how I am to be regarded. We have our orders…

he

has

his

orders, and it matters not at all.” He tried to slow his breathing, saw aides gathering, keeping a distance. “Very well. I will do what I must. We have a plan to carry out, and we shall carry it out, whether anyone beyond this headquarters cares to assist us or not.”

KASSERINE PASS—FEBRUARY 21, 1943

The fighting had moved more to the west, a hard struggle across rocky hills draped by pockets of brush, dense thickets of fir trees. Rommel had pressed his people forward, fighting the hesitation and mistakes in his own command as much as his troops fought an increasingly tenacious defense from Allied artillery and antitank positions.

The truck moved downward, and he could see the river now, the Hatab, the remnants of a wrecked bridge, replaced with one by his own engineers. Tanks were moving across, black smoke rolling upriver past the tumbled wreckage of half-tracks, one long-barreled cannon shattered into pieces, embedded in the soft mud. He ordered the driver to slow, the truck rolling past a burnt-out tank, what Rommel knew now to be a Sherman, its turret tossed aside, smoke rolling up from the bowels of the crushed machine. There were trucks, four of them, what had been part of a column caught on the road, the wrecks shoved aside by his engineers. He stared at each one, men still inside, burnt black, one man in a grotesque curl around the steering wheel. Bodies were scattered all across the mud, draped across blasted trees in the patches of wood, helmets and bits of men and uniforms and weapons in every low place, the mud barely disguising the fight that had rolled over the uneven ground. The troops had met face-to-face here, and Rommel could see it now, men from both sides, black bloody stains, bayonets on broken rifles, more trucks, a jeep, its wheels bent out, like some toy crushed under a massive foot. Along the riverbank were more bodies, a neat row, pulled out of the mud by men who could not simply pass by and do nothing. The truck rolled over the makeshift bridge and Rommel did not look down, did not care about the uniforms the men wore, did not look into the face of death. The thought skipped through his mind—which of us left the greater number of dead at this place?—but he pushed it away, thought, it makes no difference. Someone else will deal with that, will do the arithmetic, the paperwork. His attention was drawn forward, a wide clearing beyond the bridge, a vast sea of destruction, blasted tanks, half-tracks, trucks attached to artillery pieces. He saw now that much of the equipment was undamaged, some of it half-buried in mud-filled ditches, crews abandoning their vehicles to escape on foot. There were more cannon, unhitched, pointing east, ready for the fight, but the artillerymen were long gone, leaving behind stacks of boxes, unused shells. He saw trucks full of gear, boxes, ammunition of every sort, crates of magazines for small arms, and more, all the equipment necessary to build a campsite, tents, cookstoves, crates of tinned food.

There were hard blasts to one side, thunderous explosions falling in unison along the hillside behind him. His driver turned, looked back at him, and Rommel pointed forward, shook his head. We’re not turning back, not now. His truck rolled farther out through the open ground, and he stared across the field, saw more undamaged trucks, a half-track sitting by itself, the front wheels bent and shredded by a mine. He had to see more, put his hand on the driver’s shoulder, the truck slowing, stopping. He did not raise the binoculars, had nothing to observe, the heavy mist and smoke swallowing the trees in front of him, where the fight still poured over men on both sides. He stood still for a moment, felt Bayerlein beside him, knew there were questions, why they had stopped, why

here.

Rommel stayed silent, felt the hard weight of what he was seeing. It was unending, an ocean of American steel, every truck fueled and equipped, a silent army, missing only the men who had pulled away, who did not yet have the heart to stand and make a fight against Rommel’s powerful machine. But they will, he thought. They will learn and adapt, and they will come again. They are children with too many toys, but after this fight, they will have grown, and they will have learned, and they will bring their machines and their equipment back into the fight, new trucks and new tanks and new airplanes. He thought of Hitler’s description,

mongrel race

. What does that matter here?

NEAR THALA, TUNISIA—FEBRUARY 22, 1943

He had driven away from the fighting, had seen enough of it for himself, what the commanders had been relaying to him since first light. Despite the enormous success at Kasserine, the pathways to Tébessa and Le Kef were now strongly fortified, massive numbers of artillery pieces targeting any German armor that attempted to push through the Allied defense. On both fronts, the German push had been stopped, the Allied resistance growing stronger, helped by the increasing support from the north, British artillery and fighting men who added to the American barrier.

The truck rolled into the open ground in front of the block building, the headquarters for the Twenty-first Panzer, more trucks already there. Kesselring was waiting for him.

“I

would like to suggest to the Führer that you be officially named army group commander for all of Africa. Your performance here has certainly silenced anyone’s criticism of you.”

Rommel let out a breath, drank from a bent tin cup, warm water cutting through the dust in his throat. Kesselring was smiling at him, and Rommel had seen that too many times, felt no warmth from the man. He glanced now at Westphal, the young man accompanying Kesselring to the meeting. He had wanted to embrace his former aide, still felt enormous affection for the young colonel, had followed the young man’s progress as a field commander. Westphal was not smiling at all, had greeted him with a scowl of concern, something Rommel also recalled.

“So, now I am to be rewarded for my efforts? I am no longer thought of as a

defeatist

?”

“I never thought of you that way. There has been misfortune, frustration. Regardless, you deserve this command, and I know the Führer will see it that way. Even the Italians will agree.”

Rommel stared into the dingy water, thought, so no one knows of this

promotion

yet, not the Führer, not the Italians.

“My apologies, Albert, but there is little left to command here.”

“Of course there is! We have earned a brilliant victory here! And even if the enemy does not withdraw completely, our bridgehead position in Tunisia is more than merely sound. It is impregnable! We need a man in command who is impregnable himself.”

Rommel set the cup aside, looked again at Westphal, thought,

he

doesn’t believe I am impregnable. For good reason.

“I regret that I must decline the honor of your offer. I am certain that General von Arnim has the Führer’s full confidence. The strength of our Tunisian position is a credit to his leadership.”

Kesselring moved toward a chair, sat, rubbed a hand on his chin. There was silence for a long minute, then Kesselring said, “I would hope you would reconsider. But no matter. Have you given the order to withdraw?”

“Yes. There is no purpose to be served by holding our current position either here or west of Kasserine. The enemy will continue to build his strength, and we have used up all we can put into this fight.”