The Rising Tide: A Novel of World War II (25 page)

Read The Rising Tide: A Novel of World War II Online

Authors: Jeff Shaara

Tags: #Fiction, #Historical, #War & Military, #Action & Adventure

They passed by camps, scattered tents, disguised by brush piles, pitched under shattered donkey carts, dug into muddy hillsides. There were farmhouses as well, many of them destroyed, those still standing a certain target for the dive-bombers, a death trap for anyone who sought a little dry comfort. They passed men and equipment as well, grumbling sergeants and military policemen, who battled with words and tempers, fighting to keep the flow of supplies and men moving forward. There were tanks as well, the M-3 Stuarts mostly, machines that made the generals nervous, reports having come frequently from Montgomery’s army that German tanks could roll right through the fire from the Stuart’s small cannon. But on the road into Tunisia, the tanks Eisenhower passed by were American, part of the First Armored Division’s Combat Team B, men who had come ashore at Oran, who had punched the French resistance away, who’d swept the city clear for the infantry. The tank drivers kept their machines out to the side of the road, so their steel treads wouldn’t obliterate the roadbeds altogether. They drove instead alongside the caravan, churning the deep mud, tossing back high wakes of brown spray. Eisenhower watched them as he passed, men who smiled, who stood tall in the tank turrets and saluted, word passing by wireless radio that someone

big

was moving up with them. He waved, wondered if they knew anything of the enemy they were going after, if they questioned the power of these machines that carried them once more toward the war.

“I

have analyzed our situation to great extent. I have ordered various rehearsals of our proposed advance by experimenting with different types of machinery, trucks, tanks, armored vehicles of every kind we have at hand. I tested them all to see which ones were best suited to the conditions in which we find ourselves. They were consistent in one key regard. None of them worked.”

Kenneth Anderson was a rugged, compact man, thick chested, with a face that never broke a smile. He seemed perfectly at home in the sea of mud. Eisenhower had not expected so much gloom from the man, waited for some sign that Anderson’s plan still included an attack on the enemy.

Anderson continued, “I have spoken to many of the local farm people around here, French mostly. They say the rainy season extends into February. I had thought that wouldn’t hold us back, but then…it is damned well going to hold us back. Unless you can have the American armor brought forward at a more rapid pace, and unless I can begin to receive double the supply caravans now reaching this area, double the ordnance, double the petrol, I am convinced that no attack should begin for at least six weeks.”

Eisenhower paced the small room, the headquarters of the British Fifth Corps. There were radios to one side, a cluster of men gathered in what seemed to be a large closet. Noise spilled from the room, a sudden burst of swearing coming across the communication line. Anderson moved that way, pulled the door closed, said, “My apologies, sir. I try to maintain some decorum on the communication lines, but too many of these men have fought the greater part of their war against the sludge at their feet. I suspect they’ll feel better when they face a human enemy. Assuming, of course, you believe the Huns are human.”

It was Anderson’s notion of a joke, no one laughing.

Eisenhower stood with his hands on his hips, said, “Don’t waste your efforts trying to keep your men from being pissed off. Hell, everybody’s pissed off. I’m pissed off. I expected a fight up here, I expected to be in Tunis by now.”

Anderson seemed to bristle. “Sir, we have done all that was possible.”

Eisenhower held his hand up. “Never mind. I’m not attacking you, General. My

decorum

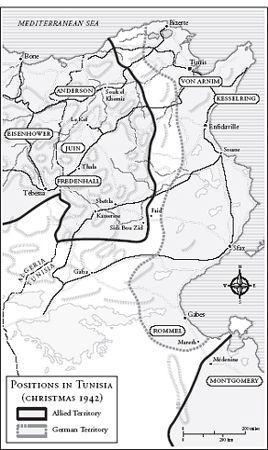

is suffering too.” He moved toward one wall, stared at a large map of Tunisia. “I had hoped that by now your people would be closing in on the ports, keeping the Germans pinched against the seashore. The enemy in front of you is still concentrated in the mountain passes and defensive positions close to the sea, right?”

“Mostly, yes.”

“Rommel’s people are still in the south, at Mareth, right?”

“Quite.”

“That leaves a hefty gap between them. We need to cut those roads, keep them split apart. I had hoped that by now, we could be pushing an American armored column to the sea, to cut the German supply lines to Rommel, cut the whole damned country in half. I want a spear driven right through Tunisia, aimed…here. These coastal towns, Sousse or Sfax. Maybe Gabès. Do we know how well positioned Rommel is in that area?”

“Not completely. Monty has only reported that there is no enemy directly in his front.”

“I’ve seen Monty’s reports. It would be convenient to our purposes if General Montgomery pressed Rommel a little harder, keeping a clear eye on what kind of shape Rommel’s in, where he’s digging in. Make sense to you?”

“Quite, sir.”

There was sarcasm even in Anderson’s response. It was Anderson’s way, an air of superiority that Eisenhower had already experienced. He had no energy for anyone’s snottiness, not now, not after so much disappointment, not after so much good planning had come apart in the rain. He stared at the map.

“Your people need to continue to strengthen their positions and support the French to your right flank.”

“Unfortunately, sir, the French require more than our support. They seem game enough, but should the Hun direct his attack into their portion of the line, there isn’t much the French can do to stop it.”

“My plan, General, has always been to support them with American units. It makes sense politically, since you and I both know that the French have some…discomfort taking orders from you. One more thing. Up until now, we’ve been piecemealing our troops among the British units, which, until we got organized, couldn’t be helped. Speed was the priority, and putting fighting men on the line took precedence over everything else. But we have to move past that now, create an organized front, and I think coordination is best served by separating the units, putting American soldiers into American commands, giving them their own part of the line.”

“I quite agree, sir.”

Eisenhower was surprised that Anderson had no objection, had expected the man to fight for every soldier he could add to his section of the line.

“Well, good. Glad to hear it. General Fredenhall will command the American Second Corps.”

“Yes, sir. I have made his acquaintance.”

Eisenhower stared at the map again. “I can’t stomach a six-week delay, General. Is there any way you can push your people forward slowly, shelling positions to their front as they go? Infantry could move with some stealth in these conditions, and once enemy positions are captured, armor can come up to hold the place. Then, do it again, like a damned game of leapfrog.”

“I quite agree, sir. It would have to be methodical, but it could be done. But unless the French to our right move with us, our flank would be exposed. We could open ourselves up to some vulnerability there.”

“Yes, I know. We can’t just ignore the weakness there. Well, the whole damned First Armored Division is headed up here. We can position them where we can make good use of the French and not just order them into a meat grinder.” Eisenhower turned, saw Butcher sitting in a corner, the man’s raincoat glistening in the dull light.

“Let’s mount up, Harry. I want to get to the French position, have a talk with General Juin. Wake up the drivers.” Eisenhower looked toward Anderson again. “How do you get along with Juin?”

“Splendidly, sir. Decent sort of chap. His men, however, won’t obey British orders.”

“That’s why we’re getting our people up here as quick as we can. They’ll listen to Fredenhall.”

“What of Giraud, sir?”

The name stuck in Eisenhower’s gut like a cold, dull knife. “He’s in overall command of the French troops throughout North Africa. He answers to Darlan, and I’m told that the French soldiers actually respect him. Most of them, anyway.”

Anderson seemed surprised by Eisenhower’s show of diplomacy. “I’m told, sir, that your headquarters received a rather touchy demand from him only this week. I don’t wish to intrude where my authority does not extend—”

“Giraud sent me a note, insisted he be given command of the entire military operation in Tunisia. Have you received any

orders

from him?”

“Certainly not.”

“And you won’t. It’s just his way. He has to crow like a rooster, make sure we haven’t forgotten him, make a grand show once in a while to let his people know he’s putting France first. I’ve learned to put up with him, because I

have

to.” Eisenhower turned toward the door, saw Butcher standing in the opening, staring out into a blowing swirl of rain. “General Anderson, with God’s help, we’ll win this thing. But before we pray for anything else, let’s pray for some good weather.”

FRENCH HEADQUARTERS, TUNISIA—DECEMBER 24, 1942

“There is a call for you, General Eisenhower.”

Eisenhower was surprised, looked at Juin, who stood, backed away from the table, made a short bow. “Right this way, General. Please use the telephone in my room. I shall allow you privacy.”

Eisenhower followed, saw the telephone, the French general ordering people away. He waited for the door to close, picked up the receiver, heard the voice of Clark.

“What is it, Wayne?”

The words filled him, another piece of the absurd puzzle, a black comedy that never seemed to end. He put the phone down, moved out through the doorway, saw Juin, Butcher behind him, several French aides. They watched him silently, and he looked at Butcher, knew the man was reading him, knew that something important had happened.

“You okay, Skipper?”

Eisenhower felt himself wanting to laugh, fought it, reached a hand out toward Juin, the man responding with a soft grasp.

Eisenhower said, “I am terribly sorry to report to you, General, that according to General Clark, Admiral Darlan has been shot. Reports suggest strongly that he is dead.”

Juin released his hand, moved to a chair, sat, the other Frenchmen staring in silence, strangely emotionless. Eisenhower wanted to say something consoling, but there were no tears, the men pondering the news with uncharacteristic silence.

Butcher said, “What does this mean, sir? What do we do now?”

Eisenhower shrugged his shoulders. “It means that right now, we go back to Algiers.”

T

he death of Darlan had come by the hand of an assassin, a young Frenchman named Bonnier de La Chapelle, who claimed to be a staunch supporter of Charles de Gaulle. Power now fell to Henri Giraud, the next man in the chain of French authority. Within twenty-four hours of Darlan’s death, Giraud authorized the young man’s execution. Eisenhower was surprised that despite all his demands and displays of bravado, Giraud accepted the authority with some reluctance. The morass of civilian affairs was apparently no more appealing to him than it was to Eisenhower. But Giraud accepted the role that events had thrust upon him. Much of the authority that he had so angrily demanded at Gibraltar was now his.

Eisenhower could not help but feel the anxiety that Darlan’s death might cause, pro-Vichy officials rising up in noisy protest, disrupting the already tenuous civil order in the far-flung territories across North Africa. But the business of the army went on, the French accepting Giraud’s expanded authority with barely a ripple, the civilian officials seemingly too occupied with protecting their own positions to be concerned with who was at the top. Ultimately, Eisenhower realized that no matter the twisted confusion that seemed a normal part of French political life, considering the grief and turmoil that had fallen on his head, and across the entire Allied command for their cordial dealings with Darlan, in the long run, Bonnier de La Chapelle might have done the Allies an enormous favor.

T

he Allied forces continued their snail-like organization, Anderson sparring with German dive-bombers and artillery attacks, the Americans pushing forward to the south, organizing alongside the French, under Lloyd Fredenhall’s command. Despite the sluggish Allied progress, Anderson’s forces attempted to drive the Germans back toward the key objectives of Bizerte and Tunis. In seesaw battles that accomplished little, villages changed hands, crossroads were contested, but in the end, the only clear victor was the mud.

Though progress continued to be made, Eisenhower could not avoid one cost of the pressures he endured every hour of every day. Once back in Algiers, after dutifully speaking at Darlan’s funeral, Eisenhower was defeated by a foe he was too worn-out to avoid. He came down with the flu.

The vast mountains of details, problems, and controversies had driven Eisenhower to a sickbed. But his illness allowed for no relief. The details flowed through and past him still, the mundane and the routine suddenly eclipsed by a piece of news no one in headquarters had expected. In the midst of the chaotic planning, the insufferable weather, the energetic buildup of the enemy in front of them, word came that a summit meeting of the Allied leaders was to take place in mid-January, less than three weeks away. The meetings were customary, but this time the setting was not. Rather than gather their aides and officials in London or Washington, Winston Churchill and Franklin Delano Roosevelt had decided to come to North Africa.