The Rise & Fall of ECW (3 page)

Read The Rise & Fall of ECW Online

Authors: Tazz Paul Heyman Thom Loverro,Tommy Dreamer

One year later, though, Studio 54 closed down, and Heyman decided to get into the wrestling business full-time. So he became a manager, and Paul E. Dangerously was created. Heyman started out as the manager of the Motor City Madmen, a tag team on the independent circuit in the northeastern United States. He soon moved down to Florida and managed some wrestlers there, and quickly moved on to one of the hotbeds of wrestling and the home of the NWA—Memphis, Tennessee. And it wasn’t very long before Memphis got a glimpse of the future of professional wrestling.

“I kind of got fired my first day,” Heyman recalls. “They were kind of conservative, and I’m from New York and I’m not very conservative. I’m pretty liberal and extreme. Jerry Lawler pulled me aside and said, ‘I want you to go out there and have that real New York attitude and tell people how you are going to take over everything.’ I did it in a kind of crass manner, I guess. I told the story about Hotaling’s News Agency, a famous newsstand in New York on 42nd Street. It has newspapers from all over the world. I talked about how I would go there and buy the Memphis

Commercial Appeal

and how Jerry Lawler is always written up as the big man in Memphis. Now that I have been down here for a day, and now that I have seen what this place is about and what Jerry Lawler is about, if Jerry Lawler is the big man in Memphis, no wonder I have encountered so many lesbians in the state of Tennessee.”

In the Tennessee of 1986, that was just not done. “To me, it was nothing, a cheap joke, but to Jerry Lawler and Jerry Jarrett, I might as well have gone on there and talked in tongues,” Heyman says. “They pretty much told me I was finished up the next day. I was advised, finish up tomorrow, go home Monday. I figured my last thing better be a bang, and I was sent out to the ring managing a guy then named Humongous, who actually ended up being a big star—Sid Vicious. I decided that they can’t fire me if I can tear the house down. I did everything I could to drive those people into a frenzy, and by the time we were done, the whole Mid-South Coliseum was chanting, ‘Paul E. sucks! Paul E. sucks!’ I had the place rocking.

“When I got in the back Austin Idol pulled me aside and said, ‘Why are you managing somebody else, you should be managing me?’ I said, ‘I think I am being sent home tomorrow morning.’ Austin Idol assured me, ‘No, no, nothing of the sort.’ He walked into Jerry Lawler’s office and said, ‘I want the New York kid to manage me. I want Paul E. Dangerously to manage me.’ The next thing you know, I am the top manager in the territory, and we are shaving Jerry Lawler’s head and we are front-page news.”

So Heyman was rehired and managed the team of Austin Idol and Tommy Rich. He helped fuel a feud between Idol and Lawler with a match in which the loser got his head shaved. Lawler lost, so they go about shaving Lawler’s head in a sold-out Mid-South Coliseum in Memphis. “The place is rioting,” Heyman says. “It took place inside a cage, and Austin Idol is thinking, ‘We are never going to get out of this cage.’ The cops couldn’t get us out. Fans were barracading the cage. Tommy Rich was drunk. He had just flown in from Japan, and he had helped Austin Idol beat Jerry Lawler. He was too smashed to realize how much danger he was in. I’m 21 years old, these people are trying to kill us, and I am thinking, ‘This is great heat. I have made it.’ I am too young and stupid to realize that these people are really trying to kill me. People wait a long time, a lifetime in this business, to hit a moment like that, and three months in, I am in the middle of it. It was the right place and the right time.”

Wrestling is, by nature, a transient business, and often, to move up, you have to move around. Heyman moved on to work for one of the major wrestling organizations, the AWA, run by wrestling legend Verne Gagne out of Minneapolis. Heyman was sent to Las Vegas to help run the AWA television shows being produced there. And this put him in the middle of the politics of the wrestling industry, which rival or in many cases surpass those of any other business in America.

One of the most popular tag teams in the NWA was called the Midnight Express—Dennis Condrey & Bobby Eaton—and they were managed by Jim Cornette, the high-profile manager and promoter of Smoky Mountain Wrestling. But in 1987 Condrey disappeared and was replaced by Stan Lane. Condrey later resurfaced and contacted some friends in the AWA and said he wanted to team up with a former tag team partner, Randy Rose. The two had teamed up before Condrey hooked up with Eaton, so Condrey wanted to call them the Original Midnight Express. The AWA wanted Percy Pringle, who would go on to WWE fame as Paul Bearer, the manager of Undertaker, as the manager for the Original Midnight Express. But Tommy Rich, who had just joined the AWA, told Gagne that they should use Heyman for the Original Midnight Express promotion. So Heyman flew to Las Vegas, where they would tape four weeks of television shows at once at The Showboat hotel and casino. Heyman was managing the Original Midnight Express, but he was on a short leash. If they didn’t like him, Pringle would manage the tag team.

“I had one chance to impress,” Heyman said. “I went out there and did everything I possibly could to tear down the house and say as many controversial things as I possibly could. After the first hour, they said I was hired. They were on ESPN daily back then, different versions of the show all spliced up. So I had a platform where in a promotion filled with guys who had been seen for the past few years, I am the freshest face. The ESPN time slot is on every day around 4

P.M

., and I am there doing the most insane interviews I could. The AWA was so old school in its mentality. A manager would walk on and say, ‘I want to discuss armbars and toeholds and headlocks and dropkicks,’ and I am out there saying, ‘I am walking down the street in New York and hanging out with my friend Jon Bon Jovi, and Bon Jovi has a song out now, called “Living on a Prayer,” and that is exactly what our opponents are, living on a prayer if they think they can beat my men.’ I would tie topical references in with politics or a sensitive issue, and would use it to my advantage. Anything that was a hot button in society, I would talk about. This was not done back then, and it made me stand out and drew a lot of attention to me.”

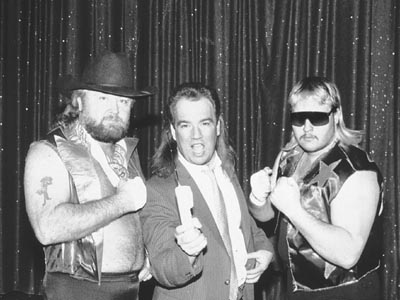

Dennis Condrey, Paul, Doug Gilbert.

Staying on the move, six months later Heyman went to work for a small promotion starting up in Georgia called Southern Championship Wrestling. He also helped open a promotion out of Chicago at the same time called Windy City Wrestling. It was there, at the age of 22, that Heyman got a chance to start booking wrestling shows—determining who won, who lost, who was used, how they lost, what they said, basically scripting the entire show. Heyman loved it. “The creativity was great,” he remembers. “I was responsible for not just one segment of the show, but every segment of the show. It was fantastic. Here I am at 22 years old, I am telling these veterans who wins and loses, and why. Windy City Wrestling catches on fire, and we are selling out shows all throughout the Chicago area.”

He was still working with Southern Championship Wrestling as well, and while in Atlanta, Heyman ran into a familiar face, someone he remembered from his days as a kid photographer hustling his way into wrestling matches—a wrestler with a magnetic personality and a great feel for the business named Eddie Gilbert.

Gilbert, the son of Tennessee wrestler Tommy Gilbert, broke into wrestling in 1979 as Tommy Gilbert, Jr., in honor of his father. He later changed it to Eddie Gilbert and became a popular wrestler in the Mid-South Wrestling promotion. In 1986, Mid-South changed its name to the Universal Wrestling Federation, and Gilbert added the nickname “Hot Stuff.” He started to play a role as manager as well, and managed wrestlers like Sting and Rick Steiner early in their careers, as part of a stable of wrestlers called “Hot Stuff, Inc.” He also began his career as one of the best bookers in the business, getting the most out of unknown and unproven wrestlers. The UWF was later bought out by Jim Crockett Promotions and the NWA, where Gilbert went to work. But he chafed under the controls there, and wanted the independence to book shows. So he went back on the independent circuit, working for the United States Wrestling Association and then the Global Wrestling Federation. He moved on to the Contintental Wrestling Federation in 1989, where he hooked up with Heyman, whom Gilbert asked to help him with the booking in the CWF. Heyman moved to Montgomery, Alabama, where he worked as Gilbert’s assistant booker and still made trips to Chicago to run two or three popular shows monthly for Windy City Wrestling.

They worked well together, and when Gilbert got an offer to join the old Jim Crockett Promotions—which was now about to become World Championship Wrestling, with Superstation television owner Ted Turner buying the operation. Gilbert told Dusty Rhodes, who was booking for the organization at the time, that they should consider bringing Heyman in the promotion. Heyman met with Rhodes.

Gilbert vs. Cactus Jack.

“I was offered two different jobs—they wanted to groom me to be the color commentator, and they also wanted me to do something shocking, to shake things up there,” Heyman said. “They were losing talent to Vince at the time, like Tully Blanchard. The deal was that I would bring in my Midnight Express team against Cornette’s Midnight Express. They would be the babyfaces and I would be the strong heel. We negotiated the deal, and on November first, 1988, I went to Atlanta and did this very different type of storyline on television. My team, the Original Midnight Express, jumped Jim Cornette’s Midnight Express.”

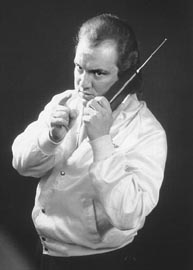

It was at WCW that Heyman, as Paul E. Dangerously, developed that manager character and his signature gimmick—a cell phone. “Back then cell phones were big and cumbersome, weighing about fifteen pounds. I always had a cell phone in my hand. ‘Where’s the phone, where’s the phone?’ I would say. I would crack people in the head with the phone. I would be talking to Wall Street investors on the phone.” On the Saturday night WTBS show, Heyman, as Paul E. Dangerously, hit Cornette with the cell phone and he was gushing blood.

Rhodes was eventually moved out as a booker, and Crockett took over. He started a booking staff, which was essentially a writing staff, with a promoter named Jim Barnett, a wrestler named Kevin Sullivan, Gilbert, and Heyman. It was too many cooks for Heyman, who was gaining a reputation as one of the industry’s up-and-coming creative bookers. The politics of booking by committee caused dissension—Ric Flair would take over booking after a power struggle—and stifled creativity, and Heyman, whose style rubbed some of the old-school members of the business the wrong way, was gone from WCW in 1993.

This would be a turning point for Heyman, and for the industry as well. He was 27 years old and had been in the business, in one form or another, for fourteen years now. “I was burned out on wrestling at the time,” he said. “I was going to get involved in New York radio. I had some offers. One of the things I hated about wrestling was that the guys who had been in it for a long time would bitch and moan and say they could have done this better or that better, and why don’t they do this or that, but they never did anything to change the industry.”

Around that same time, the culture of America was changing. A rock ’n’ roll president, Bill Clinton, took office. Eighty people died in Waco when government agents attacked David Koresh and the Branch Davidian compound. A car bomb exploded in the World Trade Center underground parking garage—all signs of a changing, tumultuous world. Culturally, the country was also going through changes. Johnny Carson had left the

Tonight Show,

replaced by Jay Leno. The music scene was being influenced by the Seattle grunge movement and groups like Pearl Jam and Nirvana. Hip-hop music had also come onto the scene and was starting to shape the entertainment industry. And the wrestling business, after the growth of

WrestleMania

in the eighties, was in a down spin, the product having grown stale.