The Rise & Fall of ECW (25 page)

Read The Rise & Fall of ECW Online

Authors: Tazz Paul Heyman Thom Loverro,Tommy Dreamer

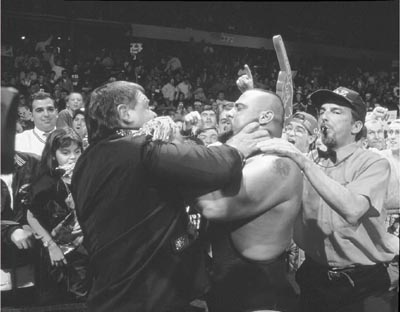

Jerry Lawler and Tommy Dreamer.

The collaboration certainly created a buzz for both promotions. “It was good for both,” Ron Buffone remembers. “It was good for the talent because they got a chance to showcase their talent. It was good for World Wrestling Federation because they got a chance to show us, and it was good for ECW, because it brought ECW into the mainstream.”

The cross promotion took a big step at the February 24, 1997,

Monday Night Raw

at the Manhattan Center in New York. Heyman, Raven, Tazz, Tommy Dreamer, Beulah, the Dudleyz, The Eliminators, Sandman, and the Blue World Order appeared on the show.

Announcer Jerry Lawler confronted Heyman and the ECW wrestlers in the ring that night. “You ought to get down on your hands and knees and thank your lucky stars that you are even getting a chance to plug your stinking Pay-Per-View on

Monday Night Raw,

do you understand that?” he said. “And why Vince McMahon would allow this, I’ll never know.” Heyman and Tommy Dreamer walked Lawler around the ring, backing him up, and cornered him.

“It was so exciting for us because as the revolution, the ECW revolution, we were finally going to be able to show everybody out there in the world that we were legit,” Bubba Ray Dudley recalls. “We really went in there as a team, and as a bunch of guys who believed in ourselves and the company.”

Lawler was perplexed by the whole idea and the way the ECW wrestlers acted. “I guess you could attribute it to maybe being arrogant, cocky, self-confident, whatever, but they had an attitude like they were better. I was thinking you guys don’t realize how lucky you are to get to be involved and have this worldwide exposure all of a sudden.

“The first thing I remember when I saw these guys were how small they were,” Lawler says. “Everybody looked like miniature wrestlers running around, and I remember commenting, after looking at Tazz, to Vince, ‘He looked a lot bigger on the Lucky Charms box, you know, McMahon.’ This was while Tazz was wrestling in the ring. Then Tazz came over to me and said something to me about that.”

Tazz grabbed Lawler, and the two had to be separated. And at one point Heyman had to be held back from going after Lawler.

Heyman, standing in front of the crowd outside of the ring, grabbed a microphone and said, “Does this show suck without ECW or what?” Fans chanted, “ECW! ECW!” while Sandman, with his Singapore cane, and Dreamer led the cheers in the ring. “The whole place was chanting ECW, ECW,” Dreamer said. “We did ECW-style matches on

Monday Night Raw.”

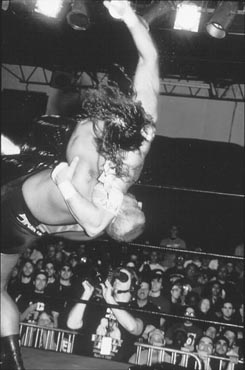

There was one memorable scene involving the giant

Raw

letters at the wrester’s entrance from backstage that were a trademark of the show. “I was wrestling Mikey Whipwreck,” Tazz recalls. As Tazz slammed Mikey Whipwreck, Sabu came out and climbed on top of the R and tried to jump off. “He fell off the R onto Team Tazz,” Tazz says. “This is live TV, and I had never done live wrestling before. It was an inside joke. We used to make fun of him for it.

“It was a lot of fun, the Invasion stuff. It didn’t last long, but it was cool.”

“ECW invading

Raw,

to me, started the whole attitude era, where anything could go and anything could happen on

Raw,”

Tommy Dreamer says. “Just watch. ‘Look, they even brought in guys from another promotion.’”

It brought a different look to

Raw.

“Back then in 1997, they didn’t have guys in the ring doing what the guys there do now,” Tazz says. “WCW didn’t have those types of guys either. The athletes weren’t wrestling a fast-paced aggressive style. I feel Paul Heyman created that with ECW. That was the hardcore style, that was the extreme style.”

At the same time that Heyman is trying to call attention to ECW, he is also working desperately behind the scenes to calm the fears of the Pay-Per-

View company and get ECW’s first Pay-Per-View back on the schedule.

“We had to prove to Hugh Panero what I had said to Keller. I had witnesses,” Heyman says. “We had a long discussion about the New Jack incident, and assured them that New Jack would not be on the first Pay-Per-View. I told him I would send him a script for the first Pay-Per-View, so he could see what we were going to do, up front, with the promise that they could pull the plug on us any time that we violated the script, and our fans had bombarded Request TV over that time, so they realized this was going to be a money maker. They put us back on the schedule for Sunday night, April 13, 1997, which, by the way, WCW moved their

Nitro

to the night after.

“I never felt in my heart that I wasn’t going to get us back on the schedule. I couldn’t accept that possibility. The only thing that could happen was us getting back on the schedule. Life doesn’t exist without that happening. It was so tough. Everyone thought it was the end. ‘What if they don’t get us back on for a year or so? How will we last?’ I told people we would get back on, and soon. We’ll make it. Thank God we did. And the second week of January 1997 it was announced we were back on. Then everyone was pumped up, and the whole dynamic changed. It was like, ‘We fucking did it.’ The cockiness was there and chests were out, and it was like, ‘Motherfuckers, we beat the odds at every turn.’ We pulled this off. The warrior came out in everybody.”

The “warrior,” though, had to agree to some unwarrior-like stipulations before Hugh Panero would move ahead with the Pay-Per-View on Viewer’s Choice. First, the Pay-Per-View company had to have approval of a script before the show, and there was not to be any outrageous or excessive blood, gimmick bouts that used blood as the main draw, or any extreme man-on-woman violence. The show would not air until 9

P.M

., two hours later than typical wrestling Pay-Per-View shows, and would cost $19.95—$10 less than the other companies sold their shows for at the time. Even with the restrictions, it was a chance for ECW to start raking in the Pay-Per-View revenue and get on the map of that lucrative world.

All Heyman had to do was to keep everyone from going crazy and killing either themselves or each other until

Barely Legal 1997

finally took place. “Going into the Pay-Per-View, the week before, everybody pretty much knew what they were doing,” Heyman recalls. “But everybody lost their minds going into this Pay-Per-View. It was the first time that the nerves got to everybody. Nobody knew what life was going to be like on the flip side. Some people had delusions that this was going to make us all millionaires, not realizing that this was just the first step in getting full Pay-Per-View clearance. It was just the next step in our evolution. It was a life-and-death step, but just one step. So many people didn’t see that.”

Viewer’s Choice was trying to wield its considerable power. First, it didn’t want Joey Styles to go it alone as the commentator for the show. Typically, in most telecasts, there are two people, a play-by-play person and a color analyst, and the Pay-Per-View company wanted a color analyst for the show. But that was not the way ECW did its telecasts, and Heyman battled them on the issues.

“Joey Styles was frazzled, because the Pay-Per-

View company insisted that I have a color commentator on the show, that it was unheard of to do a one-man broadcast on Pay-Per-View,” Heyman explains. “But I insisted on it because that was how we were doing our TV show, and I wanted it to be authentic. It was a lot of pressure for Joey, but he shouldn’t have felt the pressure. He could do it. That was why I gave him the job.”

They also didn’t want Ron Buffone to be the producer. “The Pay-Per-View company did not want Ron Buffone,” Heyman says. “The week of the show they pulled a fast one on me and said if Ron Buffone is the director, we’re not going to do the Pay-Per-

View live. I said I am not going to turn my back on the people who have been with me. They backed down. Ron couldn’t sleep the entire week, especially since we were doing all these packages and commercials for the Pay-Per-View. Ron was on edge, and we were at each other’s throats. He very much appreciated that I had his back, and I did have his back, but we were still at each other’s throats.”

Buffone did appreciate Heyman’s loyalty, both to him and to the product that had gotten them this far. “The battle to get on Pay-Per-View was immense. They didn’t want to give us a shot. They thought we were too extreme. And we were an unproven commodity on Pay-Per-View. They didn’t want to take a chance. They wanted a minimum guarantee. They had brought in their own people literally to pull the plug on us at any time. It was quite difficult getting on. Even in the process of getting on, they wanted to bring their own people in to produce and direct the Pay-Per-View.

“To Paul Heyman’s credit, and I have nothing but the greatest respect for him in this regard, he went not only with the wrestlers but with the production team that got him there,” Buffone points out. “Paul believed that these were the people who got me here, these are the people I am using. You don’t get to the Pay-Per-View with this production crew and creating a look and a certain type of feel, and then hand over the creative reins to somebody else. Paul believed the look was very important, and to go with something else could destroy the product. If you notice, the promos were always done from one camera perspective, never two where it was cut cleanly in between—all those promos were done one take, straight through, period. That made everyone sharp and on point and creating that intimate feel where you are not cutting away from you. You are literally getting to the wrestler’s character, and he draws you in, and you believe what he says.”

It wasn’t enough that Heyman had to fight these battles with outsiders. He also had to fight the battles among his own people. One of the featured bouts for

Barely Legal 1997

was to finally have Sabu and Tazz face each other, after Tazz spent pretty much an entire year calling Sabu out. Somebody now had to win, and somebody had to lose, and the booker—Heyman—would decide.

“Sabu asked, ‘Who is going to win, me or Tazz?’” Heyman recalls. “I said, ‘I am going to have Tazz win, then turn you heel with Rob Van Dam. I’m going to have Fonzie turn on Tazz after the match, saying that Fonzie bet on Sabu, even though Fonzie was Tazz’s manager.’ Sabu was upset because his uncle, The Sheik, never believed in doing jobs—losing matches. So Sabu said, ‘Don’t bother turning me heel. I will wrestle the show, but it is my last night. I want you to release me after the show.’ I wouldn’t do that.

“Everybody was falling apart. Nobody knew what was on the flip side. Some people seemed to be more afraid of the success than actually looking forward to it, and didn’t know how to handle it and the anticipation.”

Heyman recalls that the night before

Barely Legal,

the promotion held a tribute dinner at the Hilton hotel in Philadelphia for Terry Funk, who was going to wrestle in a three-way for the ECW Heavyweight Championship. “One of the big draws of

Barely Legal

was that the grand old man of hardcore, Terry Funk, would be challenging Raven in the impossible dream, the ECW title. We had captured people’s attention with this Funk storyline so much that he was this beloved figure. To make it a complete weekend, we did a Terry Funk banquet. It was more about ECW than about Funk, but it was a chance to say thank you to Terry and get everybody together.”

Not everybody. Raven was not there. Heyman didn’t want him there because of his role the following night in the Terry Funk title bout. “It was a Three Way Dance, and you didn’t know Raven was going to be Funk’s opponent,” Heyman explains. “It was to be the Sandman, who had the big feud with Raven over Sandman’s son; Stevie Richards from the Blue World Order, who broke away from Raven and was no longer Raven’s lackey; and Terry Funk. The winner of the Three Way match was to fight Raven for the title. Because Funk and Raven were going to be opponents, I didn’t want them up on the podium together, so I didn’t have Raven come to the banquet.

“So Raven was pissed off because Sabu, who owed a lot of his career to Funk, was there, and so was Tazz. For Sabu and Tazz to be in the same room at the same time, Raven felt why couldn’t he be there? Raven kept saying, ‘I should have been there, I should have been there.’”

Finally, the sun came up in Philadelphia on April 13. The day had arrived. All the hype, the hysterics, the triumphs, and the tensions were in the past. There was nothing now for anyone to look forward to or look back on or complain about or criticize. There was only one thing for anyone in and around ECW on this spring day in Philadelphia—make

Barely Legal 1997

a success.

No one wanted to consider any other options.