The Red Journey Back (12 page)

Read The Red Journey Back Online

Authors: John Keir Cross

What

really saved the situation—kept us going in those last two strange days of

suspense and waiting—was Miss Maggie Sherwood. Maybe I should say a word or two

about her—Dr. K.’s niece, you know, as Mike has already mentioned.

She

had come out to the launching site with us and was living in one of the huts,

same as we were. She and Mike were as thick as thieves—they’d struck up a real

friendship as soon as they had met in Chicago, and I must say they suited each

other well. Maggie was about the same age as Mike, and her hair had a tinge of red

in it (his was bright carrot). She was a big strong kind of girl, always

leaping

about—never still for a moment; tremendous fun,

really—plenty of energy about her. Not very pretty—I can’t say that; but a nice

sort of squashed-in face

[2]

that looked just swell when she smiled—and she was nearly always smiling.

Anyway,

that was Maggie more or less, and as I say, she pulled us through those last

two days. She was as lively as a cricket—always hatching up some scheme or

other to amuse us. When she wasn’t in the thick like that she was off for hours

on end with the bold Mike, the pair of them with their heads close together,

and whispering, as if they were planning something. Once, I remember, they both

were missing for several hours—nobody had any idea where they were. We searched

everywhere—all over the camp; and it was Archie who spotted them at last,

clambering stealthily down the long metal ladder that led up to the tiny

entrance hatch in the side of the

Comet.

When

we asked Mike what the pair of them had been doing for so long in the rocket’s

cabin, when it was strictly speaking out of bounds till we went into it on

business as it were, he just shrugged.

“Oh,

nothing. Just taking a last look around, you know—at least Maggie was. Don’t

forget she mightn’t ever see it again—or her uncle either for that matter—or

even any of us. You never know. We might blow up before we ever leave Earth at

all—or we might be hit by a meteor in space—or there are always the Vivores

when we do touch down on Mars, whatever they might be.”

“Cheerful,

aren’t you,” sniffed Jacky (but there was just a little shake in her voice—for

any of these things

could

easily happen to us on a job like this: it’s no simple trip to the seaside,

shooting off to Mars, you know

. . .

).

But

at last the time did pass, and it was the final night of all. Dr. K. had

returned from his trip into Chicago and we all had a kind of solemn supper

together before going to an early bed. Mike’s mother and father were there, of

course, and J.K.C., and all of us who were going—us three and Katey and Archie.

And—needless to say—the inevitable Maggie.

We’d

meant to have speeches—some kind of celebration, almost; but you know, when the

time came it just couldn’t be done—just couldn’t. Even Maggie was subdued; and

for the first time, just before we all parted for bed, I saw that she wasn’t

all just bounce and energy after all—there was a softer side.

She

went close up to Dr. K., and her eyes were very wide and a little bit starry,

the way Jacky’s always go when tears aren’t all that far away. And she

whispered—perhaps I shouldn’t really have been lis

tening,

but I couldn’t help it, I was so close to Dr. K. myself.

“Berkeley,”

said Maggie, very softly (it was the ridiculous name she always called him), “Berkeley,

I wish you’d say right now that I could come with you tomorrow—I wish I could

have your permission.”

He

shook his head.

“You’re

all I have in the world, Berkeley,” she went on, “and I’m all you have. We

really ought to be together. There’s plenty of food in the rocket—and plenty of

spare air from the breathing apparatus—and you’re well under the weight

complement, even allowing for Mr. MacFarlane and Dr. McGillivray on the way

back.

. . .

Won’t

you say yes?”

“I

can’t, my dear,” he answered, with a saddish kind of smile. And she shrugged.

“Oh

well. I gave you the chance at least. In that case I guess I won’t be around

tomorrow morning—you know I don’t like partings, even for a little time; I

always hated railway stations. I’ll just stay out of sight somewhere.

. . .

”

She

put her arms around his neck and kissed him. And his eyes were a bit starry

too—in fact, all our eyes were when she came around us one by one and told us

she wasn’t coming out in the morning.

“I’ll

say my so-longs now,” she said, “and we’ll leave it at that. O.K.? Be seeing

you.

. . .

”

And

that was it. We all trooped to bed, feeling very subdued. I remember, after I’d

undressed and put the lamp out, standing for a long, long time by the window of

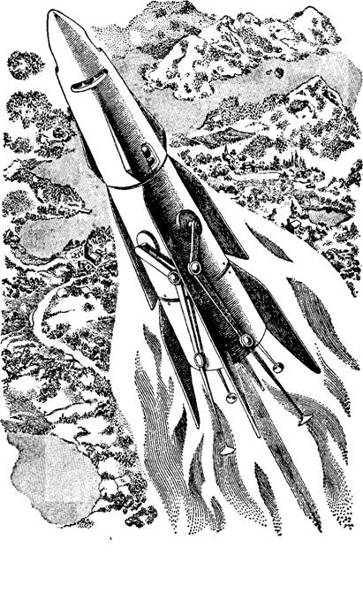

my bedroom, looking out to the tall slim shape of the

Comet

, almost a mile away. It gleamed a

little in the moonlight—gleamed silver; like the strange far spire of some

cathedral of the future, maybe, in a shadowy city all huddled in the drifting

ground-mist which wreathed the tripod base.

I

looked beyond—into the star-clustered sky. In a few hours we ourselves would be

up there too—hurtling into the unknown—or, at least, to some of us, the partly

known. Would we ever find Steve and Doctor Mac even if we did reach Mars? Would

they be alive if we did find them? Would we ourselves ever return?

My

gaze came back to Earth, attracted by a slight movement around the corner of

one of the encampment huts. A small figure was moving stealthily forward in the

direction of the rocket; and I recognized the unmistakable features, in a

sudden glint of moonshine, of Maggie Sherwood.

I

thought I understood her feelings. She, who was being left behind—left

alone

, separated from her friends, her only

relative—was going out across the silent field for one last forlorn look at the

great rearing structure of the

Comet.

Then, in the small hours, perhaps, she would creep back desolately to bed—would

waken in the morning to the great explosive roar which would tell of our

departure—would see the vast, silvery cigar shape rise slowly, spouting fire,

gaining speed, more and more speed, until at the last, when it was no more than

a tiny pencil against the pale blue of the morning sky, it would disappear

suddenly in one last little spurt of drifting smoke

. . .

and she

would cry a little, perhaps, and then leave the encampment for Chicago, to take

up normal life in the boarding school there, as had been arranged.

I

felt very sorry for her as I crept into bed; and so lay for a long time, just

thinking and dreaming—and waiting; until, in spite of everything, I dozed off

to sleep.

. . .

(I

hope you’ll forgive this bit

of “fine writing,” by the way, as J.K.C. calls it: I did feel it all rather

strangely that night. Ah well.)

It

was cold—terribly cold—when we drove next morning to the ship. We shivered, in

spite of the warm clothing we wore. We assembled in the reinforced concrete hut

close beside the base of the gigantic machine that was to be our only home for

so many, many weeks.

We

said our farewells—to Mike’s mother and father, to Dr. K.’s assistants, to dear

old J.K.C., who was in a pale kind of awe at last, and silent for once, now

that the moment of climax had come.

One

by one we mounted the long swaying ladder and went through the little dark

entrance hatch in the

Comet’s

gleaming side. We took our places—still in silence, following out the

instructions that had been dinned into us at a dozen conferences.

Katey

was very white—her lip trembled a little. I saw Jacky take her hand and squeeze

it comfortingly—after all, she had been through it all before.

. . .

Archie

took up his position beside Dr. Kalkenbrenner at the control panel. The Doctor

looked around inquiringly and we all nodded from the bunks in which we lay—to

which, indeed, we were strapped, in readiness for the tremendous impact when

the

Comet’s

own jets should come into use after the release of the booster.

Twisting

my head around on the sorbo pillow, I could see J.K.C. and some half-dozen

assistants on the ground, close to the door of the concrete hut. J.K.C. waved

once, then he and the others trooped inside for shelter from the terrific blast

there would be.

A

long silence. I heard Dr. K. counting slowly to himself: “Seven—six—five—four—three—two—ZERO!”

And

instantly there was an immense explosion, seeming almost to shatter our

eardrums. Far beneath, the ground seemed to rock and tilt—then the concrete hut

seemed to reel and steady itself—receded—grew smaller, smaller and smaller

. . .

and

with the danger from the blast now gone, J.K.C. and the others—tiny, tiny black

figures—rushed out once more, waving ecstatically after us as, in full triumph,

the

Comet

rose higher and higher into the pale sky.

. . .

the

Comet

rose higher and higher into the pale sky

The

speed of our ascent increased—the figures, the hut itself—all were lost to

view. Dr. Kalkenbrenner, by the instrument panel, cried out to us in warning as

he prepared to release the booster and set the

Comet’s

own jets into action.

A

second explosion—even more gigantic-seeming than the first. An immense hand

seeming to press me down and down into the soft mattress

. . .

and

everything swam before my eyes and went black.

. . .

When

I came back to consciousness—slowly at first—all was quiet. We were in full

flight—were already many, many hundreds of miles away from Earth, heading

toward the Angry Planet we knew so well—and yet so slightly too.

I

looked around. Some of the others had already recovered also—others were still

blacked out. In the confusion of the moment it was as if we were still in the

dear old

Albatross;

and I remembered with a chuckle the bewilderment we had seen then on the faces

of Doctor Mac and Uncle Steve when the door of the store cupboard had wavered

open and we three stowaways had floated out to confront them.

I

set to loosening the straps that held me, so that, for old times’ sake, I could

sail off the bed in the old weightless way. As I twisted around to reach the

buckle, my eyes fell on the metal door of one of the storage cupboards in the

Comet’s

cabin, not unlike the old storage

cupboard on board the

Albatross.

For

an instant I thought I was dreaming—that I was still in a mist from the black-out

and so had confused the two journeys.

But

I was not dreaming! Not by a long chalk! The door of the

Comet’s

storage cupboard was wavering

open—someone was floating out toward us, as we had floated on that other

occasion!

I

cursed myself for feeling so sentimental about Maggie Sherwood the evening

before—for wasting all my good sympathy on her. I knew now why she had crept

out from the encampment in the moonlight to steal toward the rocket!