The Red Army Faction, a Documentary History (49 page)

Read The Red Army Faction, a Documentary History Online

Authors: J Smith

It was an error not to seek the solution in the metropole itself rather than using a young national state to intensify matters, because the decision should have been based on the balance of power hereâbecause it concerned the prisoners, who embodied the struggle here, and because it was a question of isolating the FRG. In connection with an action in the metropole, the goal of which was to polarize the metropole and create a break between the people and the state, the method usedâhijacking an airplaneâcould only neutralize the attack because the people in the plane found themselves in the same situation, treated as objects, as the imperialist state always and in all ways places people, thereby destroying the goal of revolutionary action.

The incorrect thinking behind the action that played against the commando, and which the federal government could count on in its planning, started with the fact that it was obvious that the commando would do whatever it could, and would continue to negotiate as long as it saw any hope of the FRG freeing the prisoners. This played against the commando, allowing the government to develop its strategy. As for the SPD, it chose to resolve matters by carrying out a massacre, as it had in Stockholm, because it is always ready to discard its popular image when American interestsâstable rule in the centerâare attacked. At the time, Schmidt said, “It was impossible to know if it would result in an acceptable outcome.” It amounted to a decision in favor of a military solution at a time when a guerilla victory in the FRG, the key country for the reactionary integration of the West European states, would have meant a decisive setback for imperialist plans for reconstruction. It was a leap forward for the reactionary counteroffensive to consolidate its internal security mechanisms in Western Europe. But with Stammheim and Mogadishu, a centerpiece of social democratic policy, the hidden war, was unmasked. The imperialist state appeared shamelessly and openly reactionary; it no longer shied away from comparisons with its fascist past, but embraced them. The “desert foxes” of Mogadishu were to be an example for German youth. But at the same time, the political weakness of the metropolitan states, the internal fragility of the entire structure that appeared so powerful from the outside, was made obvious as never before.

Red Army Faction

May 1982

_____________

1

A slightly different translation of this paragraph appeared in our first volume (478). The version presented here is more true to the German original.

Using Honey to Catch Flies

S

O F

AR, THE PRESENT VOLUME

of our study has examined how the guerilla groups met the challenges and answered the questions posed by the development of their conflict with the state in the 1970s. We have seen how the 2nd of June Movement split over the question of where and in what way to pursue the struggle, and how the Revolutionary Cells became an important reference point for the new protest movements, thanks to its fluid structure and movementist strategy. As for the RAF, the May Paper articulated a series of proposals that had been debated and discussed for several years and constituted an attempt to re-ground the guerilla in the new movements that were rocking the FRG in the eighties.

At this point, we intend to discuss the state, which despite its hidebound proclivities, had not wholly avoided learning lessons from a decade of armed struggle. We have already seen how â77 spurred on preexisting tendencies of repression and control, witness the rise of the

Zielfahndung

and the use of Horst Herold's computers to track its targets. What must also be appreciated is that some state actors were thinking outside of the box, examining methods other than repression, considering political rather than military means of terminating the armed struggle.

It is to these that we will now turn our attention.

As we have at times belabored, West Germany had been an intensely conservative society in the 1960s. Even after the APO and Willy Brandt's “Dare more democracy” ushered in a new, more open age, many institutions retained their authoritarian reflexes. For these, it remained an article of faith that left-wing political violence could only be answered with repression, and the more of it the better.

Surveillance and arrests were buttressed by psychological warfare, for which the courtroom was always an important theatre. At first, various trials were used to push the idea that the RAF was a hierarchical organization with brutish leaders. The so-called “ringleader thesis” blamed Baader, Meinhof, Raspe, Meins, and Ensslin for all the group's activities, explaining the guerilla away as a consequence of a few individuals' charisma, rather than any deeper political conflicts. As a result, the five were charged with attacks even where there was no evidence directly implicating them, in what amounted to a show trial at a special courtroom bunker built within the Stammheim prison compound, with psychologists, psychiatrists, and even neurologists being enlisted to pathologize the “leaders” and their supporters.

1

At the same time as the ringleader thesis was being used for propaganda purposes, implying the RAF was made up of seductive maniacs and idiot followers, a “collective responsibility thesis” was developed, according to which all RAF members were responsible for all RAF attacks. If the ringleader thesis was the cornerstone of the Stammheim trial, the collective responsibility thesis was used to justify the prosecution of the other RAF members for criminal acts even when there was no direct evidence supporting such charges.

2

This second approach became all the more important after â77, once all five “ringleaders” were dead.

The collective responsibility thesis was further refined during Angelika Speitel's 1979 trial, drawing in part on statements Speitel was alleged to have made while hospitalized and under sedation, after having been shot during her arrest. (She was questioned by police officers dressed as doctors.)

3

Judge Wagner, who presided over Speitel's trial, followed this by sentencing Stefan Wisniewski to life in prison on December 4, 1981, finding him responsible for the Schleyer kidnapping and murders, although there was no evidence against him other than his membership in the RAF. Similarly, on June 16, 1982, Sieglinde Hofmann received a fifteen-year sentence in connection with the murder

of Jürgen Ponto, despite the fact that the court had to acknowledge that she had not been at the scene of the killing.

4

(This was also despite the fact that she had been extradited from France on condition that she not be charged with this crime, as the main evidence against her was the hearsay testimony of Hans-Joachim Dellwo, whose work for the prosecution will be detailed below.)

5

All this was criticized by civil libertarians, and yet it must be stressed that neither the RAF nor the prisoners made a big deal about the collective responsibility thesis, which actually fit well with the guerilla's own understanding of its internal process and political responsibilities. Although Brigitte Mohnhaupt and Helmut Pohl had each testified in 1976 to the effect that commandos operated on a need-to-know basis, the position that every RAF member was willing to publicly stand by every RAF action was voiced by more than one prisoner. In this way, they could affirm their ongoing solidarity with one another, as well as their political identity as captured combatants (see

pages 273â274

).

If trials constituted the stage on which the state presented its narrative, the drama would have been incomplete without the cooperation of turncoats, former guerillas or supporters who had flipped and agreed to collude in the psychological warfare campaign.

A string of such “repentant guerillas” had been trotted out as witnesses in various trials in the 1970s. First, there was Karl-Heinz Ruhland, a mechanic who had worked with the RAF, and who after being arrested with a stolen car testified against his former friends. Next, an actual member of the guerilla was flipped; Gerhard Müller, who was arrested in 1971, had killed a police officer, but the charges were dropped and he was provided with a new identity and cash payment in exchange for his testimony, which included the smear that the RAF executed its own members rather than allowing them to leave.

6

At the time, the FRG had no crown witness

7

law permitting reduced sentences for those who provided state's evidence, and as such the deals

between the attorney general and these witnesses fell into a legal grey zone. Indeed, outrage at Müller's testimony played an important part in discrediting the Stammheim show trial, with

Spiegel

arguing that it constituted “an intentional breach of the law.”

8

Müller and Ruhland's testimony was further compromised by the fact that both men had been peripheral to the RAF. This was to prove typical, as most of those who flipped in the 1970s were simply supporters who found themselves facing heavy charges in circumstances for which they were ill-prepared. The most damaging of these were probably Volker Speitel and Hans-Joachim Dellwoârespectively the husband and brother of RAF members Angelika Speitel and Karl-Heinz Dellwoâwho were arrested in the heat of â77, and who subsequently testified that the prisoners' lawyers had smuggled guns into Stammheim. This testimony was not only used to send attorneys Armin Newerla and Arndt Müller to prison, it also provided cover for the shim-sham investigation and discrepancies surrounding the prison deaths of the RAF's leading figures in October 1977.

Over the next five years, Volker Speitel's testimony was repeatedly presented at RAF trials, making him a “star witness” who could not be cross-examined by the defense, and who did not even deliver his testimony in court, all due to alleged “security concerns.”

9

This despite the fact that not once in the RAF's history had a crown witness or defector been targeted by the guerilla.

The antiterrorist §129a had been crafted as a net to snare and intimidate such supporters. Under this law, over three thousand preliminary proceedings were launched against the left between 1980 and â88, only 5 percent of which actually resulted in charges being laid (the average for other laws was 50 percent)

10

, and less than 2 percent resulted in a conviction.

11

The paragraph's real function was twofold: to elicit information, whether or not there existed any evidence that could stand up in court, and to intimidate the guerilla's sympathizers.

12

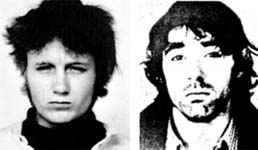

Gerhard Müller (left) and Volker Speitel, two of the most notorious crown witnesses of the 1970s.

Prison conditions constituted the other half of this equationâyears of isolation and abuse creating extreme pressure, with the only option for relief being to flip. This is the real reason why the state felt compelled to crack down on the prisoners' various attempts to communicate with one another, and why it resisted association: for a long time, the main view was that harsh treatment was the best way to elicit a jailhouse conversion, and that the prisoners had to be kept apart in order for this process to do its work.

This strategy had some successes, but at the same time it came at a significant cost, as prison conditions themselves became one of the main reasons that supporters joined the guerilla. As Dieter Kunzelmann has observed, “By 1972, practically the whole founding generation of the RAF were behind bars. Yet there was still a second generation and a third generation. Why? Primarily because of the conditions of imprisonment and state-organized terror.”

13

Given that the hard line so often proved counterproductive, the question must be asked: why was it pursued for so long?

Institutional inertia is one part of the answer. Police and state organs were full of individuals ideologically committed to the iron fist. The revolutionary left was viewed as a social pathology, perhaps the asset of a foreign enemy, and only superficially a political movement. The proposed cure was a combination of quarantine and surgery, isolating the revolutionaries while hitting them hard. Despite the mediocre results, many on the right maintained that waging a “war against vandals and partisans”

14

was the only sensible approach when dealing with “terrorists.”

The hard line was also a consequence of jockeying within the state, as the CDU/CSU attempted to win votes by painting the SPD/FDP government as “soft on terrorism”:

The Christian Democrats, most notably CDU's party leader Helmut Kohl, deliberately evoked associations of chaos and democratic weakness and blamed the government for its “inability to govern.” He painted the spectre of “political vandalism” and a relapse into “the bad period of the Weimar Republic.” Berlin's parliamentary CDU party chairman Heinrich Lummer spoke of a “degeneration of democratic morals and principles.” While Federal President Karl Carstens (CDU) warned of a “weak state that, like in 1933, could not defend itself against its enemies.”

15