The Red Army Faction, a Documentary History (18 page)

Read The Red Army Faction, a Documentary History Online

Authors: J Smith

66

. Fran Yeoman, “Diplomats Suspected Entebbe Hijacking Was an Israeli Plot to Discredit the PLO,”

Times

Online, June 1, 2007.

67

. Marc A. Celmer,

Terrorism, U.S. Strategy, and Reagan Policies

(Contributions in Political Science) (Westport: Greenwood Press, 1987), 66.

68

. Graham H. Turbiville, Jr.,

Hunting Leadership Targets in Counterinsurgency and Counterterrorist Operations: Selected Perspectives and Experience

(Hurlburt Field, Florida: Joint Special Operations University Press, 2007), 16.

69

. Karl-Heinz Dellwo,

Das Projektil sind wir

(Hamburg: Nautilus, 2007), 142.

70

. Helmut Pohl and Rolf Clemens Wagner, interviewed by

junge Welt.

71

. Viehmann (1997), 6.

72

. Fritz Teufel, “Indianer weinen nichtâsie kämpfen,” late May 1979. This text will be published along with other documents from the 2JM in a forthcoming documentary history to be copublished by Kersplebedeb and PM Press.

The Antinuclear Movement: Old Meets New

I

F THE ONWARD MARCH OF

generations affects all human endeavor, this is particularly true of the left, to such an extent that it often seems to keep time by the changing of the generational guard, and even remembering the lessons of just a few years past can be a challenge to what frequently appear as movements driven forth by youth itself.

As the guerilla languished, just a little farther afield history's march was welcoming a new generation into the fray. Merging and clashing with veterans of the APO in a variety of struggles, the most important of these in the latter half of the 1970s was certainly the direct-action movement against nuclear power.

The FRG's three main political parties had all held pro-nuclear positions since the 1950s. Indeed, at first, even social critics wondered if cheap nuclear power might provide a science fiction fix for the evils of industrial capitalism, as when Ernst Bloch waxed eloquent about the atom's potential to “make flushing meadows from wasteland, flowering spring from ice, in the blue atmosphere of peace.”

1

Of course, outside of the left, the new and mysterious high-tech energy source held a different appeal. For the first generation after Hitler,

nuclear energy gave hope that technical prowess might replace military might as the measure of the nation's strength. As one journalist from the liberal newspaper

Die Zeit

explained:

There was no way to express German national feeling after the war. This would have been interpreted as a Nazi attitude. West Germans instead constructed their new national identity around economic growth and power. Nothing better symbolized this than the nuclear industry.

2

This vision of nuclear power as a symbol of pride, vital to the national interest, was bolstered by the first oil shock in 1973. That year, the price of oil quadrupled as a result of an OPEC decision to limit production following the Yom Kippur War; this came shortly after the collapse of the Bretton Woods monetary system in 1971. The world economy was sent into a deep recession, the post-World War II boom drawing to a final close.

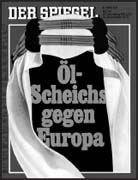

Spiegel sums up the imperialists' evaluation of the oil crisis: “Oil Sheikhs Against Europe.”

As the price of oil continued to spiral upwards (by the end of the decade it would be fourteen times what it had been in 1973), the West German ruling class saw both danger and opportunity. On the one hand, petroleum imports at the time accounted for almost 60 percent of the country's primary energy consumption, and so the skyrocketing prices had the potential to strangle the economy.

3

On the other, the oil crisis created an opening for the FRG to use atomic energy to gain leverage in the world market.

At the time, the country was ruled by a “Social-Liberal” coalition made up of the SPD and the much smaller Free Democratic Party (FDP), and the government's economic strategy was for the FRG to position itself as a producer of capital-intensive, high-value exports, with the state mediating between employers and the working class to ensure social peace. This “Model Germany,” a term coined by SPD Chancellor Schmidt during his 1976 election campaign, involved phasing out labor-intensive industries that produced inexpensive products and making substantial state investments in the

research, development, and infrastructure upon which the high-tech sector would depend. Nuclear power was key to this strategy, and by the middle of the decade that sector alone was receiving one-third of all federal R&D moneys, with the FRG becoming second only to the United States in international sales of light-water reactors and fuel cycle equipment.

4

Meanwhile, at home, Schmidt's 1974 Energy Program called for ten years of rapid growth in the domestic nuclear sector, with plans for more than forty new high-capacity plants supplying energy to several giant projected industrial corridors to be built in traditionally agricultural areas.

5

The anticommunist bulwark was becoming the atomic state, based on a kind of nuclear imperialism and supported by all political parties, the trade unions, and big business. The word “technocracy” is an apt description; as sociologist Christian Joppke has noted, “In response to energy crisis and economic recession, the neocorporatist elites moved closer. Not dialogue, but the repression of dissent prevailed.”

6

Faced with this ruling-class unity and a fourth estate which studiously ignored the risks associated with the new technology, most people initially favored building more nuclear plants, one poll in 1975 finding only 16 percent opposed.

7

Echoing the experience of the 1960s Grand Coalition and APO, this “unity of all democrats” made for a cocky and belligerent ruling class, while also giving its detractors a strikingly clear view of the system they were up against. Consequently, it provided an easy route to radicalization.

Social Democratic Chancellor Helmut Schmidt (above), whose “Model Germany” relied upon the labor aristocracy remaining closely tied to the corporate and state elites.

Over the course of the decade, a series of campaigns against various nuclear facilities would become linked in a mass

movement. Ironically, although reinforced by the successors to the APO New Left, notably the antiauthoritarian

Spontis

and the Marxist-Leninist party-oriented K-Groups, this movement actually originated in various Citizens Initiatives, groups initially set up by the SPD to seduce new members.

8

As the radical left was drawn in, the movement's political content became a point of contention, with the question of “violence” serving as the symbolic dividing line between those who viewed the state as something to reform and others who recognized it as an opponent to fight against.

The way this broke down varied from one place to another; for instance, in Hamburg the

Kommunistische Bund

found itself well-placed to lead the local campaign, while in Bremen and Göttingen the dominant K-Group (the

Kommunistische Bund Westdeutschland)

was in decline, and so a younger generation, more sympathetic to the

Spontis,

took the lead.

9

Coming together in a series of confrontations with the state, the antinuclear campaigns would serve as a laboratory for these groups to put their very different ideas into practice, exchanging insights and comparing results. More importantly still, their strengths and weaknesses would be made plain to see for all the new people being drawn to the struggle. It was, in the best sense of the term, a living movement.

The first major mobilization occurred in 1975 against the proposed construction of a nuclear power plant at Wyhl in the conservative

Land

of Baden-Württemberg, where the FRG borders on both France and Switzerland. Led by local farmers and professionals, and fueled by regionalist sentiments, the opposition was dismissed as irrelevant by the

Land's

CDU government and the nuclear utility, which ominously warned that, “Even if the risks of nuclear power were bigger than they actually are, we would have to accept them in the interest of freedom and democracy.” Or as

Land

president Hans Filbinger put it, without Wyhl, “the lights go out in 1980,”

10

any opposition to the plant obviously being “teleguided by Communists or Maoists.”

11

Despite the fearmongering, protesters carried out an audaciousâthough strictly nonviolentâaction against the planned plant. In the frozen month of February, hundreds of local residents occupied the

construction site and refused to move. They remained for two days before police turned on them with water cannons. Although driven away, they returned the next week, joined now by tens of thousands of people who had come from throughout the FRG, as well as from France and Switzerland. This time they built barricades.

12

Dutch social scientist Ruud Koopmans has argued that “novelty gives protesters a strategic advantageâauthorities are unprepared for new strategies, political actors, and themes,”

13

and this was certainly borne out at Wyhl, the first site occupation of its kind in Europe. As the world's attention turned to this tiny German town, so did that of the urban radical left.

14

The nonviolent occupation became a miniature village, preventing construction work and creating a political nightmare for the government. After ten months, the state blinked, declaring a “temporary” halt to construction, which would in fact never be resumed.

Wyhl was a successful first round, but the struggle against nuclear energy was just beginning. One year later, the ante was upped at Brokdorf in Schleswig-Holstein, the intended site of a nuclear power plant slated to produce 1,300 megawattsâas much power as the total energy consumption of the entire

Land.

15

As protesters assembled for what was billed as a nonviolent occupation in the spirit of Wyhl, they found that the building site had already been occupiedâby a battalion of police. As one student from Göttingen University remembers:

For the first time, we were visually confronted with the atomic state: huge police levies, barbed wire fences, dogs, a construction site turned into a fortress. That was new for us. Before that, we had not been directly confronted with the state. The student movement and the wildcat strikes of the late 1960s had occurred before our time.

16

The RAF had similarly energized a section of post-APO youth, but only a small one. One needed to be predisposed to the prisoners' struggle, and preferably live in a big city with a supporters' scene, in order to “get it.” Nuclear power, with its potential for widespread calamity, energized far greater numbers, and yet its opponents sparked a familiar

dynamic, with repression exposing the system's violent core, drawing new people and forces into what was initially a more limited conflict.