The Red and the White: A Family Saga of the American West (20 page)

Read The Red and the White: A Family Saga of the American West Online

Authors: Andrew R. Graybill

Tags: #History, #Native American, #United States, #19th Century

For his part, Baker simply wanted to return to Fort Ellis, given the space constraints at Fort Shaw that had inconvenienced his men on the outbound leg of their campaign. Thus on 31 January he led his troops southeast to Fort Ellis, where they arrived on 6 February, precisely one month after their expedition began. All told, the soldiers had traveled more than six hundred miles, and—as Baker explained in his initial report—“in the coldest weather that has been known in Montana for years.”

49

Yet even as his troops recuperated from their travails, a storm of a different sort was gathering and would soon break upon the major. In time this tempest would come to engulf not only Phil Sheridan but also William Sherman himself.

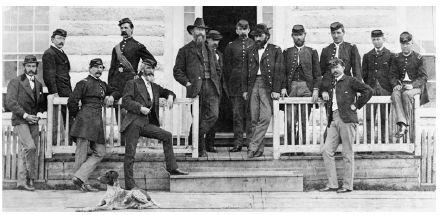

Officers of the Second U.S. Calvary at Fort Ellis, 1871. This photo depicts Baker (ninth from left, leaning with his left hand on the fence post) and some of his officers, the year after the Marias Massacre. Lieutenant Gustavus Cheney Doane is fourth from left. Courtesy of the Montana Historical Society.

The Spoils of Victory

News of the incident on the Marias reverberated throughout Montana and the larger Rocky Mountain West, trumpeted with a jingoistic fervor and greeted with elation by area whites. On 2 February the

Helena Daily Herald

ran a story that began, “The deed is done: the murder of Malcolmb Clark has been avenged; the guilty Indians have been punished, and a terrible warning has been given to others of our red-skinned brethren, who may be inclined to live by murdering and plundering the white man.”

50

Meanwhile, the

New North-West

published a resolution submitted by citizens of the Deer Lodge Valley stating, “That we do most heartily and sincerely indorse the manner of treaty then and there made [on the Marias] with those and all others of our red brethren who inhabit the soil of Montana.”

51

Neither broadsheet, however, matched the vitriol of Idaho Territory’s

Owyhee Avalanche

, which defended Baker by invoking alleged Indian atrocities and suggested hyperbolically that henceforth the army should “[k]ill and roast [the Indians] as they do the pale face. Kill the squaws so the accursed race may cease to propagate. Kill the pappooses.”

52

Expressions of gratitude poured in for Sherman, Sheridan, and Baker from all corners of Montana.

53

There were even scattered encomia for Colonel de Trobriand, who just a few months earlier had elicited jeers from the territory’s white residents for his refusal to dispatch the cavalry against the Piegans. The Frenchman explained in a smug missive to his daughter in late January, “The settlers haven’t raised a statue to me,” though he expressed confidence that they would fondly remember him after he departed for his next posting in Utah.

54

Sure enough, on a visit to Helena a few weeks later, de Trobriand was flattered when during dinner at a local restaurant the maître d’hôtel threw open the windows facing the street so that grateful residents of the city might serenade him (even as they mauled the pronunciation of his last name).

55

Sherman, however, was far less sanguine. He warned Sheridan in late January to “look out for the cries of those who think the Indians are so harmless, and obtain all possible evidence concerning the murders charged on them.”

56

In the end, the general of the army was right to worry about a backlash, although he probably never imagined that it would originate from within his own ranks.

On 6 February, Lieutenant William B. Pease, the Indian agent for the Blackfeet, wrote Alfred Sully to describe a recent visit he had made (on Sully’s orders) to an Indian camp containing some survivors of the massacre. Those Piegans who had witnessed Baker’s attack gave Pease a very different account of the native casualties suffered at the Big Bend. They explained that smallpox was rife in the camp and that only 33 men were among the dead. The rest of the 140 victims were women and children, all of the latter under the age of twelve “and many of them in their mothers’ arms.” Pease added that in the aftermath of the slaughter most of the Piegans had fled across the forty-ninth parallel into Canada, and that those Blackfeet remaining in Montana were terribly frightened “and not disposed to retaliate upon the whites for the death of their friends.”

57

Four days later Sully transmitted Pease’s report to Ely Parker, a Seneca Indian who had served as Ulysses S. Grant’s military secretary during the Civil War and in that capacity drafted the terms of surrender signed by Robert E. Lee at Appomattox; as president, Grant had appointed Parker commissioner of Indian affairs in 1869. Realizing the incendiary nature of the agent’s allegations, Sully insisted in his cover letter that by forwarding the dispatch he was not taking sides in the matter; rather, he was simply giving the Indians a fair hearing, which he believed was his duty “as their only representative.”

58

This distinction, however, had disappeared by the time Lieutenant Pease’s account became public later that month. During debate over an army appropriations bill in the U.S. House of Representatives on 25 February, a letter from Vincent Colyer, secretary of the Board of Indian Commissioners, was read aloud to the chamber. In his missive Colyer cited the dispatch of Lieutenant Pease in referring to the “sickening details of Colonel Baker’s attack,” adding that these “facts” were “indorsed by General Sully, United States Army.”

59

A heated discussion of the subject quickly ensued, as congressmen rose both in defense and in condemnation of Colyer’s accusations.

Such indignation was not confined to the halls of government. The

New York Times,

which had received an advance copy of Colyer’s letter, published a scathing editorial on 24 February. Noting that it had supported a series of recent strikes against native peoples, including Custer’s raid on Black Kettle’s encampment in November 1868, the

Times

insisted that on this occasion there could be no defense of such “butchery” and called for an official investigation.

60

Likewise, the editors at

Harper’s Weekly

suggested to their 100,000 readers that the Marias massacre was just the latest episode in “our Indian policy of extermination,” an ugly pattern that stretched back more than two centuries to the colonial period. The piece ended with a flourish, wondering whether instead of killing Indians “the army should not rather be directed against our own people, whose endless cheating and lawlessness rouse their victims to revenge.”

61

Colyer’s letter had a chilling effect within the military establishment, which was anxious to avoid the sort of public chastisement it had absorbed in the wake of the Washita debacle. On 26 February, Sherman’s office sent a telegram fraught with concern to General Sheridan, requesting Baker’s official report of the incident, which had not yet been received in Washington. Sheridan replied that he would furnish the information as soon as it was available, but then gave over the greater part of his letter to a scorching denunciation of Colyer, whom the general condemned as a tool of the so-called Indian ring, a nebulous web of supposedly corrupt individuals who profited from government contracts made through the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Sheridan went on to recount the base horrors he had seen in the West perpetrated by native peoples—rapes, thefts, and murders. He added, “It would appear that Mr. Vincent Colyer wants this work to go on.”

62

Little Phil’s rage was understandable: the hero of the Shenandoah knew he was facing one of the greatest political crises of his career.

T

HOUGH INCENSED BY

the affront to his reputation, Sheridan was also vexed by the timing of the controversy, which could not have broken at a more inopportune moment. As it happened, in January 1870 the House of Representatives began debate on legislation that had as one of its key provisions the transfer of the Indian Bureau from the Department of the Interior back to the Department of War, where it had originally resided from the founding of the United States until 1849. The military had sought to regain control of Indian affairs ever since and seemed poised to score a decisive victory that spring. The uproar over Baker’s campaign, however, went right to the heart of the explosive post–Civil War dispute over federal Indian policy and threatened to derail the transfer initiative.

63

At issue in the larger conversation about the “Indian problem” was the best method for avoiding native-white conflict, especially on the Great Plains. With the resumption of American westward expansion after 1865, most evident in the frenzied pace of railroad construction, the trans-Mississippi region had convulsed with spasms of horrific violence. None was more controversial than the Sand Creek Massacre of November 1864, in the midst of the Civil War no less, when militiamen under the command of Colonel John Chivington murdered more than 150 pacific Cheyennes and Arapahos in eastern Colorado and later displayed their scalps and severed genitalia in a Denver theater.

64

The slaughter and other army-Indian clashes throughout the late 1860s caused escalating public outrage, so that when President Ulysses S. Grant took office in March 1869 he vowed to make sweeping changes in the management of Indian affairs. Grant’s “peace policy,” as it came to be known, emphasized “conquest through kindness” and featured the use of religious groups to Christianize Indians as part of the “civilizing” proces.

65

Like most military men, Grant favored the transfer of Indian affairs to the War Department, for he believed that army officers were less prone to the corruption and ineptitude typical of civilian bureaucrats at the Department of the Interior. Grant did not surrender this conviction when he took up residence in the White House; rather, he reserved the overwhelming number of Indian agency appointments for military officers, giving only a few such positions to Quaker missionaries. Sherman and especially Sheridan were even more adamant than the president about transfer; Sheridan testified before Congress that the use of army personnel in these roles would save untold sums of money while also protecting native peoples from the vicious designs of the unscrupulous Indian ring.

66

The generals and their backers, however, faced stiff opposition from the Department of the Interior. Among the most outspoken of their opponents was Nathaniel Taylor, the commissioner of Indian affairs and also the chairman of the Peace Commission, an eight-member body established by Congress in July 1867 to treat with native peoples in the hopes of averting additional bloodshed on the Plains. Writing for the commission in January 1868, Taylor enumerated eleven key reasons why the Interior Department should retain control of Indian affairs, including the inability of the War Department to handle such vast administrative responsibilities and the inherent dangers to civil liberty posed by the maintenance of a large standing army. The crux of Taylor’s opposition, however, was the glaring contradiction between promoting peace with native peoples while simultaneously investing the War Department with total authority over them.

67

Advocates of transfer were undeterred by these arguments or the fact that they had failed to achieve their goal of military oversight of Indian affairs on several previous occasions in the postbellum period. One such failed attempt in 1867 had even been spearheaded in the Senate by John Sherman of Ohio, the general’s younger brother, but to no avail. And yet by decade’s end the ground seemed to have shifted in favor of the War Department, in large part because of renewed native-white hostilities on the southern Plains in the summer and fall of 1868. That violence led to Sheridan’s winter campaign and also caused some members of the Peace Commission to reconsider the wisdom of extending the olive branch to recalcitrant Indian bands.

Thus supporters of transfer pushed the issue vigorously as an amendment to the army appropriations bill before the House of Representatives in the early months of 1870. Surely, they thought, with Grant in office its passage was guaranteed. The partisan

Army and Navy Journal

, so often disappointed in the outcome of previous debates on the issue, expressed optimism in late February that victory was finally at hand, and that with the transfer Indian affairs would at last be overseen by “a set of officers not only respected for their integrity and professional honor, but necessarily subjected to responsibility and accountability, such as the civil service never can furnish.”

68