The Red and the White: A Family Saga of the American West (14 page)

Read The Red and the White: A Family Saga of the American West Online

Authors: Andrew R. Graybill

Tags: #History, #Native American, #United States, #19th Century

The swarm of newcomers was not the only dilemma facing the Blackfeet in the early 1860s. For at least a decade, it had been clear to natives and whites alike that the herds of buffalo on the northern Plains—once so numerous that their supply seemed inexhaustible—had begun to dwindle, raising the specter of a subsistence crisis for the Indians. In effect, the natives confronted a simple but horrifying equation: the number of white people was inversely proportional to that of the buffalo, and the trend was accelerating rapidly. The U.S. commissioners had used this fact to their advantage during negotiations that in 1855 led to a historic accord with the Blackfeet, the very last of the Plains tribes to treat with the United States.

89

With Lame Bull’s Treaty, as it came to be known, Washington officials hoped to open the northern Plains for settlement and to extend a rail line from St. Paul, Minnesota, to Puget Sound in the recently established Washington Territory.

The commissioners wrote the document to promote peace between the Blackfeet and not only the Americans but also the other native peoples of the area, including the Flatheads, Kutenais, and Nez Perces. In exchange for allowing Americans to traverse and settle in their lands, the Blackfeet were promised $20,000 in annuities for each of the next ten years, as well as agricultural instruction and schools for their children. The Blackfeet quickly soured on the deal, however; whites arrived in droves, but the Great Father did not uphold his pledges, as Indian agents came and went and the delivery of promised goods was sporadic at best. In time, the words spoken by one Blood chief at the 1855 proceedings came to sound like prophecy: “I wish to say that as far as we old men are concerned we want peace and to cease going to war; but I am afraid that we cannot stop our young men.”

90

E

VEN AS

M

ONTANA DESCENDED

into chaos during the early 1860s, so, too, did Malcolm Clarke’s personal and professional lives. If the tumult convulsing the Upper Missouri was the result of terrifyingly swift social change, Clarke’s fortunes, on the other hand, were tied, as ever, to his formidable temper and inclination to violence. His victim in the summer of 1863 was Owen McKenzie, the mixed-blood son of an Assiniboine woman and the late Kenneth McKenzie, the legendary AFC trader and founder of Fort Union, who had died two years before. Unlike Clarke’s ambush of Alexander Harvey in 1845, his encounter with Owen McKenzie pitted him against one of the most beloved figures in Montana. And this time the consequences would be dire, driving him finally from the business to which he had dedicated almost his entire working life.

The roots of Clarke’s quarrel with McKenzie are murky; contemporary accounts speak merely to a longstanding feud between the two. The contours, however, are easy enough to divine. For one thing, McKenzie was almost a decade younger than Clarke but disinclined to yield to his elders. More important were his legendary skills with horse and gun. Indeed, McKenzie was glorified throughout fur country as an indefatigable rider and a crack marksman; stories abounded celebrating his facility in chasing down bison and felling them with his rifle. Few were more taken than Rudolph Friederich Kurz, the Swiss artist who spent two years on the Upper Missouri in the early 1850s. McKenzie appears frequently in the detailed journal Kurz kept, and in one entry the European noted breathlessly, “Owen McKenzie can load and shoot 14 times in one mile.”

91

With a man as reflexively competitive as Malcolm Clarke, such fawning surely rankled.

Clarke and McKenzie had faced off at least once prior to their fatal encounter. Thirteen years earlier the two men had bet on a horse race between them. Though McKenzie shattered his clavicle when his steed stepped into a hole and pitched him headlong onto the prairie, the injured rider regained his mount and still managed to win the contest, an outcome that surely drove Clarke to distraction, especially considering the very public nature of his defeat.

92

Clarke took the second and final round, but won scorn instead of laurels.

In late spring 1863 the

Nellie Rogers,

a new 250-ton steamboat, embarked from St. Louis on its maiden voyage to the Upper Missouri. Clarke was on board, along with his fourteen-year-old son, Horace, who was returning from school in the East. Although bound for Fort Benton, the head of navigation on the Missouri, low water forced the boat to stop at the mouth of the Milk River, about two hundred miles short of its destination, and offload its cargo for overland transportation. Learning of these developments, McKenzie—who was stationed at Fort Galpin, a nearby post established the year before by a small outfit competing with the AFC—rode down to meet the

Nellie Rogers.

While there is general agreement to this point in the story among the many accounts, what happened next has been the subject of strenuous disagreement. Was McKenzie drunk (which would not have been out of character) or sober? Did he berate Clarke about some allegedly unpaid debts, or did Clarke act even before McKenzie challenged him? Whatever the case, this much is clear: McKenzie forced his way onto the boat, and Clarke fired three shots from his pistol, killing him instantly. Knowing that the younger man’s enormous popularity would likely prompt retribution from his friends, Malcolm and Horace fled on horseback to the safety of Fort Benton. Afterward, Helen Clarke insisted that the terrors of that nighttime ride, featuring packs of howling wolves, drew her father and brother closer for the remainder of Malcolm’s life.

93

Clarke steadfastly claimed self-defense, which may explain why, in contrast to his near-fatal bludgeoning of Alexander Harvey in 1845, he faced no legal repercussions for the homicide. However, according to one source, “On the river it was everywhere considered at the time a cold-blooded murder.”

94

Surely it caused Clarke’s family members some discomfort, which emerged in Helen’s biography of her father. While she conceded that both men were probably to blame for the disagreement that culminated in McKenzie’s slaying, she also acknowledged her father’s general pugnacity: “His quick temper very often led him into difficulties. His life was not faultless, but ‘He that is without sin, let him cast the first stone.’”

95

Clarke’s murder of Owen McKenzie led him to quit the fur trade, perhaps because he feared for his life. But the decision was likely an easy one anyway, since by the early 1860s the fur business was in decline, a victim of vanishing bison herds and growing native-white violence, which eroded the very relationships that had made possible the trade in animal skins. Thus in 1864 Clarke made a strategic move upriver, establishing a horse and cattle ranch at a magnificent gap in the Rockies.

96

The place did not lack for scenery: six decades earlier, Meriwether Lewis had marveled at the 1,200-foot cliffs on either side of the Missouri and thus labeled the pass the Gates of the Mountains. For his part, William Clark had a painful encounter with a cactus that lent it another, less flattering name: the Prickly Pear Valley.

97

Either way, Malcolm Clarke found it a splendid locale, well watered and complete with sprawling pastures. On it he built an impressive spread, consisting of a cabin, a smokehouse, and a saloon. And his choice of site proved prescient: on 14 July 1864 a group of four ex-Confederate soldiers from Georgia who had failed as miners made one last-ditch attempt to find gold … and discovered a placer deposit in what became known as Last Chance Gulch. A camp took root almost immediately, and in time the settlement, known eventually as Helena, was connected by stage to Fort Benton, 130 miles to the northeast. Clarke’s ranch thus became a popular way station for travelers, including notable figures like Thomas F. Meagher, the acting territorial governor, who spent a night there in December 1865.

98

Clarke found great contentment at his new ranch, which housed a growing family. In June 1862 the Jesuit missionary Pierre-Jean De Smet had married him to a young mixed-blood woman called Good Singing (known to her people as Akseniski), the daughter of Isidoro Sandoval, a Hispano fur trader murdered by Alexander Harvey in 1840, and a Piegan woman named Catch-for-Nothing. Such polygyny was not unusual in the mid-nineteenth-century West, especially in the context of the bison robe trade, which—because of the need for additional female labor in processing hides—led Indian men to take multiple wives. Although the practice was less common among white trappers, data from one historical sample suggests that one-third of those who married more than once had at least two wives at some point (the remainder took single spouses sequentially).

99

The relationship between Malcolm and Good Singing dated to at least the mid-1850s, as the first of the couple’s four surviving children, a boy named Isidoro, was born in 1856 or 1857. A daughter, Judith, came along in 1864; the birthdates of two others, Phoebe and Robert Carrol, are unknown. A fifth child was stillborn. How Coth-co-co-na felt about Malcolm’s taking a second wife is unknown, but given the frequency of plural marriage within Plains Indian societies, she likely accepted it as a standard family arrangement. The whole family lived together under a single roof.

Despite—or perhaps because of—his bellicose nature as well as his sheer longevity on the Upper Missouri, Clarke came to be idolized during the 1860s as one of the area’s most esteemed “old time pioneers.” Along with eleven other leading men in the territory, probably all of whom had moved to the region after him, Clarke incorporated the Historical Society of Montana on 2 February 1865. In this role, he took on the responsibility of enshrining for future generations the very history that he and select others had actually lived, especially since the group listed “incidents of the fur trade” as one of its two key areas of interest (the discovery of the territory’s mines being the other).

100

Though it had taken him three decades and an extended residence on the frontier, Clarke had finally attained a level of social prominence of which his father would have been proud.

I

N THAT SANGUINARY SPRING

of 1865, as the Civil War ended with Lee’s surrender to Grant at Appomattox, a fresh conflict erupted in Montana Territory. Unlike the contest between the North and the South, this new campaign did not set enormous standing armies against each other in pitched battles; rather, it was a guerrilla war, fought sporadically by small groups of armed men. And in contrast to the political disagreements that spawned the War of the Rebellion, Montana’s conflagration was effectively a race war, in which the Blackfeet, and especially the Piegans, struggled to preserve their land and lifeways from the onrushing tide of white settlers.

Racial enmity, however, was only one factor contributing to the outbreak of hostilities in Montana. Surely many of the newcomers considered native peoples culturally and intellectually inferior, especially those emigrants hailing from the South who had imbibed the racist tenets of herrenvolk democracy, characterized by a dim view of those not belonging to the supposed “master race.”

101

Even some of the federal emissaries sent to help the Blackfeet held them in low esteem, including Gad Upson, the Indian agent to the Piegans, who arrived in October 1863 and described his wards as “degraded savages” and insisted that they remained “free and untrammeled from the shackles of an enlightened conscience.”

102

Still, it was their fury over native horse theft that drove some whites to commit unspeakable acts of violence.

The American stampede into Blackfeet territory had a mixed effect on Indian horse raids. On one level, federal officials had sought to eradicate the practice, given its central role in promoting conflict between groups of Indian peoples, which destabilized the region and thus made it unsafe for intending settlers. Therefore U.S. commissioners often extracted promises from Indians to abandon raiding as a key component of the treaty-making process. At the same time, the advent of so many whites created a spike in the equine population, and raids on it proved too hard for the Blackfeet to resist. After all, the Americans’ promotion of intertribal accord had robbed young Indian men of the surest path to social advancement; after warfare, horse stealing was the next-best thing, and it mattered not to the Indians that the mounts they now stole belonged to whites and not their native enemies. It was just such an event that inaugurated the so-called Piegan War.

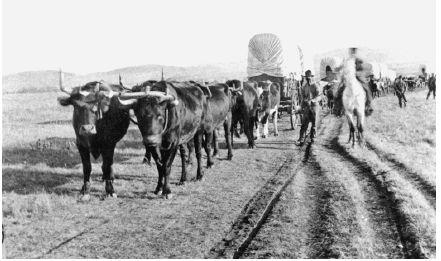

On 23 April 1865 a party of Bloods descended upon Fort Benton and made off with about forty horses. White residents retaliated one month later by ambushing a small group of Bloods who had come to the town on a peaceful visit, killing four Indians. Two days afterward, on 25 May, Calf Shirt—the prominent Blood chief—and a large war party espied a group of about ten woodcutters felling timber a dozen miles above Fort Benton, where the Americans planned to build a new settlement called Ophir. Calf Shirt, who despite his antagonism toward whites had signed Lame Bull’s Treaty ten years earlier, allegedly signaled his benevolent intentions to the terrified lumbermen, who responded with gunfire. At that point the Indians fell upon the whites. Though the Americans fought desperately, using the bodies of their slaughtered oxen as breastworks, the Indians killed every last man, stripping the bodies, scalping one of them, and cutting the throat of another from ear to ear.

103