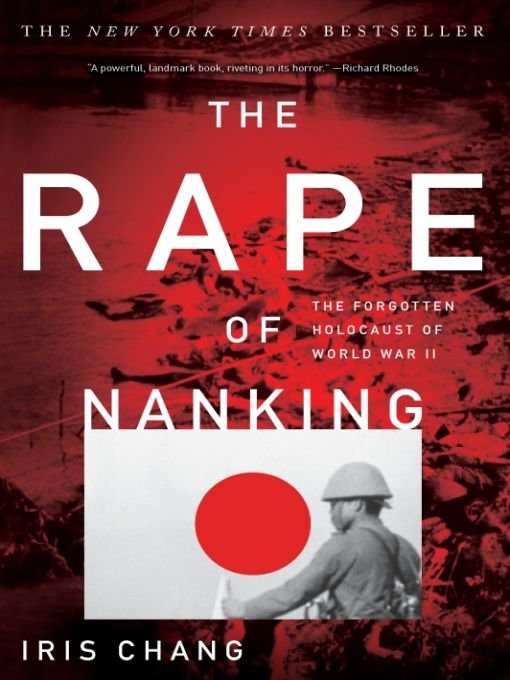

The Rape Of Nanking

Read The Rape Of Nanking Online

Authors: Iris Chang

Table of Contents

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Acclaim for the international bestseller,

THE RAPE OF NANKING

“A powerful new work of history and moral inquiry. Chang takes great care to establish an accurate accounting of the dimensions of the violence.”

â

Chicago Tribune

Chicago Tribune

Â

“Meticulously researched . . . A gripping account that holds the reader's attention from beginning to end.”

âNien Cheng, author of

Life and Death in Shanghai

Life and Death in Shanghai

Â

“Iris Chang's research on the Nanking holocaust yields a new and expanded telling of this World War II atrocity and reflects thorough research. The book is excellent; its story deserves to be heard.”

âBeatrice S. Bartlett, professor of history, Yale University

Â

“Heartbreaking . . . An utterly compelling book. The descriptions of the atrocities raise fundamental questions not only about imperial Japanese militarism but the psychology of the torturers, rapists, and murderers.”

âFrederic Wakeman, director of the Institute

of East Asian Studies, University of California, Berkeley

of East Asian Studies, University of California, Berkeley

Â

“Something beautiful, an act of justice, is occurring in America today concerning something ugly that happened long ago.... Because of Chang's book, the second rape of Nanking is ending.”

âGeorge F. Will, syndicated columnist

Â

“In her important new book . . . Iris Chang, whose own grandparents were survivors, recounts the grisly massacre with understandable outrage.”

âOrville Schell,

The New York Times Book Review

The New York Times Book Review

Â

“Anyone interested in the relation between war, self-righteousness, and the human spirit will find

The Rape of Nanking

of fundamental importance. It is scholarly, an exciting investigation, and a work of passion. In places it is almost unbearable to read, but it should be readâonly if the past is understood can the future be navigated.”

The Rape of Nanking

of fundamental importance. It is scholarly, an exciting investigation, and a work of passion. In places it is almost unbearable to read, but it should be readâonly if the past is understood can the future be navigated.”

âRoss Terrill, author of

Mao, China in Our Time,

and

Madame Mao

Mao, China in Our Time,

and

Madame Mao

Â

“One of the most important books of the twentieth century, Iris Chang's

The Rape of Nanking

will endure as a classic among the world's histories of war.”

The Rape of Nanking

will endure as a classic among the world's histories of war.”

âNancy Tong, producer and

co-director of

In the Name of the Emperor

co-director of

In the Name of the Emperor

Â

“A very readable, well-organized account . . . Chang has rescued this episode from its undeserved obscurity.”

âRussell Jenkins,

National Review

National Review

Â

“When this turbulent century draws to an end, Chang's book will shine light on the passage to a more peaceful era by invoking public consciousness on one of the darkest pages of World War II history.”

âShi Young, coauthor of

The Rape of Nanking: An Undeniable History in Photographs

The Rape of Nanking: An Undeniable History in Photographs

Â

“The story that Chang tells is almost too appalling for words . . . a carefully documented cry of moral outrage.”

â

Houston Chronicle

Houston Chronicle

Â

“A compelling piece of history that speaks volumes about humankind's inhumanity in the atrocities that have been documented and offers some vestiges of hope in the individual acts of heroism that also have been uncovered.”

â

San Jose Mercury News

San Jose Mercury News

Â

“Chang reminds us that however blinding the atrocities in Nanking may be, they are not forgettableâat least without peril to civilization itself.”

â

The Detroit News

The Detroit News

Â

“A story that Chang recovers with raw urgency . . . an important step towards recognition of this tragedy.”

âSan Francisco

Bay Guardian

Bay Guardian

To the hundreds of thousands of victims

in the Rape of Nanking

in the Rape of Nanking

FOREWORD

O

N DECEMBER 13, 1937, Nanking, the capital city of Nationalist China, fell to the Japanese. For Japan, this was to have been the decisive turning point in the war, the triumphant culmination of a half-year struggle against Chiang Kai-shek's armies in the Yangtze Valley. For Chinese forces, whose heroic defense of Shanghai had finally failed, and whose best troops had suffered crippling casualties, the fall of Nanking was a bitter, perhaps fatal defeat.

N DECEMBER 13, 1937, Nanking, the capital city of Nationalist China, fell to the Japanese. For Japan, this was to have been the decisive turning point in the war, the triumphant culmination of a half-year struggle against Chiang Kai-shek's armies in the Yangtze Valley. For Chinese forces, whose heroic defense of Shanghai had finally failed, and whose best troops had suffered crippling casualties, the fall of Nanking was a bitter, perhaps fatal defeat.

We may now think of Nanking as a turning point of a different sort. What happened within the walls of that old city stiffened Chinese determination to recover it and to expel the invader. The Chinese government retreated, regrouped, and ultimately outlasted Japan in a war that ended only in 1945. In those eight years Japan would occupy Nanking and set up a government of Chinese collaborators; but it would never rule with confidence or legitimacy, and it

could never force China's surrender. To the larger world, the “rape” of Nankingâas it was immediately calledâturned public opinion against Japan in a way that little else could have.

could never force China's surrender. To the larger world, the “rape” of Nankingâas it was immediately calledâturned public opinion against Japan in a way that little else could have.

That is still the case in China, where several generations have now been taught of Japan's crimes and of its failure, to this day, to atone for them. Sixty years later, the ghosts of Nanking still haunt Chinese-Japanese relations.

Well they might. The Japanese sack of China's capital was a horrific event. The mass execution of soldiers and the slaughtering and raping of tens of thousands of civilians took place in contravention of all rules of warfare. What is still stunning is that it was

public

rampage, evidently designed to terrorize. It was carried out in full view of international observers and largely irrespective of their efforts to stop it. And it was not a temporary lapse of military discipline, for it lasted seven

weeks

. This is the terrible story that Iris Chang tells so powerfully in this first, full study in English of Nanking's tragedy.

public

rampage, evidently designed to terrorize. It was carried out in full view of international observers and largely irrespective of their efforts to stop it. And it was not a temporary lapse of military discipline, for it lasted seven

weeks

. This is the terrible story that Iris Chang tells so powerfully in this first, full study in English of Nanking's tragedy.

We may never know precisely what motivated Japanese commanders and troops to such bestial behavior. But Ms. Chang shows more clearly than any previous account just what they did. In doing so she employs a wide range of source materials, including the unimpeachable testimony of third-party observers: the foreign missionaries and businessmen who stayed in the defenseless city as the Japanese entered it. One such source that Ms. Chang has uncovered is the diaryâreally a small archiveâof John Rabe, the German businessman and National Socialist who led an international effort to shelter Nanking's population. Through Rabe's eyes we see the dread and courage of Nanjing's inhabitants as they confront, defenseless, the Japanese onslaught. Through Ms. Chang's account we appreciate the bravery of Rabe and others who tried to make a difference as the city was being burned and its inhabitants assaulted; as hospitals were closed and morgues filled; and as chaos reigned around them. We read, too, of those Japanese who understood what was happening, and felt shame.

The Rape of Nanking has largely been forgotten in the West, hence the importance of this book. In calling it a “forgotten

Holocaust,” Ms. Chang draws connections between the slaughter in Europe and in Asia of millions of innocents during World War II. To be sure, Japan and Nazi Germany would only later become allies, and not very good allies at that. But the events at Nankingâto which Hitler surely took no exceptionâwould later make them moral co-conspirators, as violent aggressors, perpetrators of what would ultimately be called “crimes against humanity.” W. H. Auden, who visited the China war, made the connection earlier than most:

1

Holocaust,” Ms. Chang draws connections between the slaughter in Europe and in Asia of millions of innocents during World War II. To be sure, Japan and Nazi Germany would only later become allies, and not very good allies at that. But the events at Nankingâto which Hitler surely took no exceptionâwould later make them moral co-conspirators, as violent aggressors, perpetrators of what would ultimately be called “crimes against humanity.” W. H. Auden, who visited the China war, made the connection earlier than most:

1

And maps can really point to places

Where life is evil now:

Nanking; Dachau.

Where life is evil now:

Nanking; Dachau.

âWILLIAM C. KIRBY,

Professor of Modern Chinese

History and Chairman of the

Department of History,

Harvard University

Professor of Modern Chinese

History and Chairman of the

Department of History,

Harvard University

INTRODUCTION

T

HE CHRONICLE of humankind's cruelty to fellow humans is a long and sorry tale. But if it is true that even in such horror tales there are degrees of ruthlessness, then few atrocities in world history compare in intensity and scale to the Rape of Nanking during World War II.

HE CHRONICLE of humankind's cruelty to fellow humans is a long and sorry tale. But if it is true that even in such horror tales there are degrees of ruthlessness, then few atrocities in world history compare in intensity and scale to the Rape of Nanking during World War II.

Americans think of World War II as beginning on December 7, 1941, when Japanese carrier-based airplanes attacked Pearl Harbor. Europeans date it from September 1, 1939, and the blitzkrieg assault on Poland by Hitler's Luftwaffe and Panzer divisions. Africans see an even earlier beginning, the invasion of Ethiopia by Mussolini in 1935. Yet Asians must trace the war's beginnings all the way back to Japan's first steps toward the military domination of East Asiaâthe occupation of Manchuria in 1931.

Other books

Warcry by Elizabeth Vaughan

Frances and Bernard by Carlene Bauer

Alligator Park by R. J. Blacks

Tom Swan and the Head of St George Part Three: Constantinople by Cameron, Christian

The Charred Lands: Apocalypse of Fire by Josh A. Murphy

Dead End Deal by Allen Wyler

Ahe'ey - 1 Beginnings by Jamie Le Fay

Seaflower by Julian Stockwin

Forget Me Not by Luana Lewis