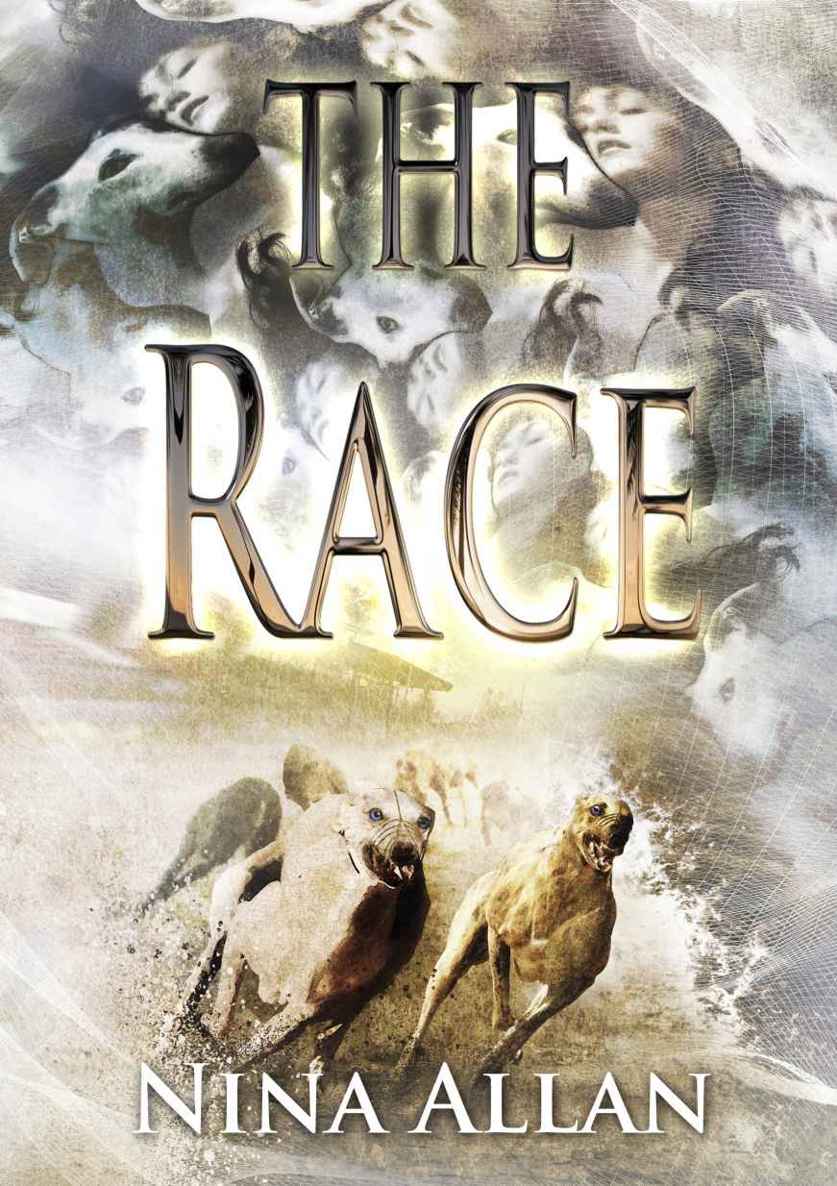

The Race

Authors: Nina Allan

The Race

Nina Allan

NewCon Press

England

First edition, published August 2014

by NewCon Press

The Race copyright © 2014 by Nina Allan

Cover Art copyright © 2014 by Ben Baldwin

All rights reserved, including the right to produce this book, or portions thereof, in any form.

Also available as:

ISBN: 978-1-907069-69-7 (hardback)

978-1-900679-70-3 (softback)

Cover art by Ben Baldwin

Cover layout and design by Andy Bigwood

Minor Editorial meddling by Ian Whates

eBook design by

Tim C Taylor

Text layout by Storm Constantine

For Chris

There have been Hoolmans living in Sapphire for hundreds of years. Like so many of the town’s old families, we are broken and divided, our instincts as selfish and our minds as hard-bitten as the sick land we live on. We have long memories though, and fierce allegiances. We cannot seem to be free of one another, no matter if we wish to be or not.

My mother, Anne Allerton, walked out on the town and on our family when I was fifteen. After she left, my brother Del, whose nickname is Yellow, went a little bit crazy. He was crazy before, most likely – it was just that our mother leaving made his madness more obvious. I was scared of Del then, for a while, not because of anything he did especially but because of the thoughts he had. I could sense those thoughts in him, burrowing away beneath the surface of his mind like venomous worms. I swear Del sometimes thought of killing me, not because he wanted me dead but because he was desperate to find out what killing felt like.

I think the only reason he never went through with it was that he knew deep down that if he killed me, there would be no one left on the planet who really gave a shit about him.

Del and I are still close, in spite of everything.

It’s easy to blame Mum for the way Del turned out, but then it’s always easier to pin the blame on someone else when things go mental. If I’m honest, I’d say that Del was troubled because he was a Hoolman, simple as that. The legends say the Hools have always been wanderers and that restlessness is in their blood. When the Hools first sought refuge in England, they were persecuted for being curse-givers, though of course that was centuries ago. I was sometimes teased at school because of my surname but most kids soon got bored of it and moved on to something more interesting. It wasn’t even as if I looked Hoolish, not like Del with his gorsefire hair and beanpole legs, but no one in class was going to risk kidding him about it, not if they wanted their head and body to remain part of the same organism.

If it hadn’t been for the dogs, I seriously think Del would have ended up in jail. Del cared about his smartdog Limlasker more than he cared about anyone, including his wife Claudia, including me.

The one exception was his daughter, Luz Maree, who everyone called Lumey. Del loved Lumey as if a fever was raging inside him, and he didn’t care who knew it.

When Lumey went missing, Del became even crazier. He swore he’d find his girl and bring her home, no matter the cost.

I think he’ll go on looking for Lumey till the day he dies.

~*~

I’ve seen photos of Sapphire from when it was a holiday resort, before they drained the marshes, before the fracking. The colours look brighter in those old photographs, which is the opposite of what you’d normally expect.

Sapphire in the old days was a kind of island, cut off from London and the rest of the country by the Romney Marshes. If you look at the old maps you’ll see that most of the land between Folkestone and Tonbridge was more or less empty, just a scattering of fenland villages and the network of inland waterways called the Settles. People who lived in the Settles got about mainly by canal boat: massive steel-bellied barges known as sleds that lumbered along at three miles an hour maximum if you were lucky. Whole families lived on them, passing down the barge through the generations the same way ordinary land-lubbers pass down their bricks and mortar. When the marshes were drained the parliament set up a rehoming plan for the sledders, which basically meant they were forced to abandon their barges and go into social housing.

The sledders fought back at first. There was even a rogue parliament for a while, based at Lydd, which was always the unofficial capital of the Settles. There was a huge demonstration, with people flooding in from all over the southern counties just to show their solidarity. The protest ended in street riots, and sometime during the night the hundreds of barges that had gathered to support the demonstrators were set on fire from the air.

More than five hundred people died, including children.

If you take the tramway up to London you can still see dozens of sleds, marooned in the bone-dry runnels that were once canals, their huge, stove-like bodies coated in rust, some of them split right open like the carcases of the marsh cows that once roamed freely over Romney but are now long gone.

Most of the sledders ended up in Sapphire, buried away in crap housing estates like Mallon Way and Hawthorne. There are those who say there are still people living on board some of the abandoned barges, the decayed descendants of those original families who refused to leave and who now scratch out a basic living in what’s left of the marshes. There’s a part of me that would like to believe those stories, because it would mean the sledders who fought so hard at the Lydd demo didn’t die in vain, but really I think they’re just fairy tales, the kind that get passed around after sundown to scare little children. Because I don’t see how anyone could survive out there now. Most of the marshland is still toxic. Del says that in some places even the air is toxic, that it’s not safe to breathe.

More than a hundred years have passed since the marshes were drained, which means there’s no one left who remembers the Settles the way they were before. I get sad when I think about that. I’ve read about how in the days before the fracking, Romney plovers used to descend upon the waterways in their hundreds of thousands. How in the spring and early autumn the reed beds were white with them, as if a freak snowstorm had passed over.

It’s hard to imagine that now. The only birds that can survive out in the marshes are crows and magpies. A magpie can eat just about anything and not get sick. Mum always used to say they were cursed.

~*~

When Sapphire first became a gas town there was a rash of new building – high-rise apartment blocks to the north of the town for the thousands of mineworkers, smart hotels and casinos along the sea front for the bosses and investors. The glory days didn’t last long, but even after the drilling works were all shut down people kept coming. First there were the government scientists who were brought in to sort the problem with the leaking chemicals – Del says they were paid vast sums of danger money just to live here. Then once the government realised the marshes were ruined, a toxic swamp basically, they turned Sapphire into a dumping ground for illegal immigrants.

Later on, though, people came because of the dogs. It’s what you might call an open secret that the entire economy of Sapphire as it is now is founded upon smartdog racing.

Officially the sport is still illegal, but that’s never stopped it from being huge.

~*~

Mum was born in London. It’s strange to think now that she lived here at all, that she exchanged her parents’ lovely red-brick house in Queen’s Park for a rickety pile of breeze blocks and clapboard on the westward edge of Sapphire, a town so worked-out and polluted that many Londoners are frightened to come here, even for a day. Mum first came to Sapphire on a jaunt while she was in college. Some of her mates had discovered the dog scene and later on Mum and a couple of the others got casual work and ended up staying for most of a summer. Mum met Dad at the track of course, where else? He was massively good looking when he was young.

“He was so different from the other men I knew then,” Mum said. “So full of life, somehow.”

It was a vacation fling that should never have lasted, they had nothing in common. But Mum got pregnant with Del and decided to stay.

I travelled to the London house once, on the tramway with Mum and Del to visit my grandparents. I was only two years old though, so I don’t remember a thing about it, not even the journey. Del was four. He says he remembers every detail, but I don’t believe him. I’m sure that what Del thinks of as memories aren’t real memories at all, they’re just things he’s been told. Other people’s memories, in other words, stories he’s heard so many times they feel like his own. Either that or they’re memories he’s cobbled together from old photographs.

There are photos of me in the London house, a sturdy-looking dark-haired toddler standing on an ironwork veranda between two strangers. The strangers are my grandparents, Adam and Cynthia Allerton. Cynthia has her face turned slightly away, glancing down at me as if she’s afraid I might piss on her shoes or something. Adam stares grimly ahead, meeting the gaze of the camera as if it were the gaze of his sworn enemy.

You won’t find my mother in any of the photos because she was behind the camera, but you can see her anyway, in Cynthia, that same eagle’s beak nose, with the little bump in the middle, the same narrow ankles and flat chest. The same nervously fidgeting hands, laden with rings.

Our visit to London lasted two weeks. Mum told me years later that she and my granddad rowed the whole time we were there, almost from the moment we arrived. Granddad kept on at her to leave my dad and bring me and Del back to London to live.

“I want you out of that dump of his,” he said. “It’s no place to bring up children.”

But Mum was having none of it. At that point she was still trying to fool herself as well as the world that she was happy.

Don’t go thinking we were poor, because we weren’t. We weren’t rich either, but we did okay. My granddad – Grandad Hoolman, not my London granddad – ran a waste reclaim business, shifting the fracking effluent from the leaking well shafts to safe enclosures. My dad went into the business when he left school, eventually taking it over when Old Man Hoolman died.

The money was good, but it was good for a reason. Grandad Hoolman died of non-specific invasive cancers and so did my dad. Dad wasn’t much over fifty when he copped it, but already he looked and moved and sounded like an old man. His insides were riddled with cancer, like mould in blue cheese, but it was really my mother leaving that finally did for him. All the fight went out of him, just like that. As if someone had reached inside and pulled the plug on his willpower.

He and Del were like poison for each other, and one of the first major bust-ups they had after Mum left was about the business.

“If you think I’m following you into shit-shovelling you know where to stick it,” Del said. “If I wanted to commit suicide I’d get hold of a shotgun and blow my brains out. At least it would be quicker that way.”

“You might as well blow them out anyway. Fat lot of good they’ve done you. Or me, for that matter.”

He sat very still in his armchair, staring at Del with his look of I-told-you-so, as if it were Del’s fault he was dying of cancer, that Del could stop it from happening if he’d only set his mind to it and stop being an arse. Del clenched and unclenched his fists and stormed out of the room. He left an atmosphere so thick it was like sulphur fumes, like a gas that might go off boom if you struck a match. I tried to find him but he’d charged out of the house somewhere. When I went back to the living room to check on Dad I found he’d fallen asleep in his armchair. The skin of his face lay slack and loose, like an old plastic bag.

The summer Mum left, the town felt airless, and hotter than a blast furnace. Dad was at work mostly, taking on extra shifts at the waste plant just so he could get out of the house. It wasn’t only because of Del, I’m sure of that, it was because of me, too. We reminded him constantly of Mum’s absence and he couldn’t face us. Del and I lived mostly out of tins, canned ravioli and baked beans and those nasty little frankfurter sausages swimming in brine. They always stank of fish, those sausages. I only have to see a tin of them on a supermarket shelf for it to come rushing back – that fishy smell and the slippery texture, sour and salty and not quite natural. Those frankfurters seemed to sum up my life, really. It was not a good time.