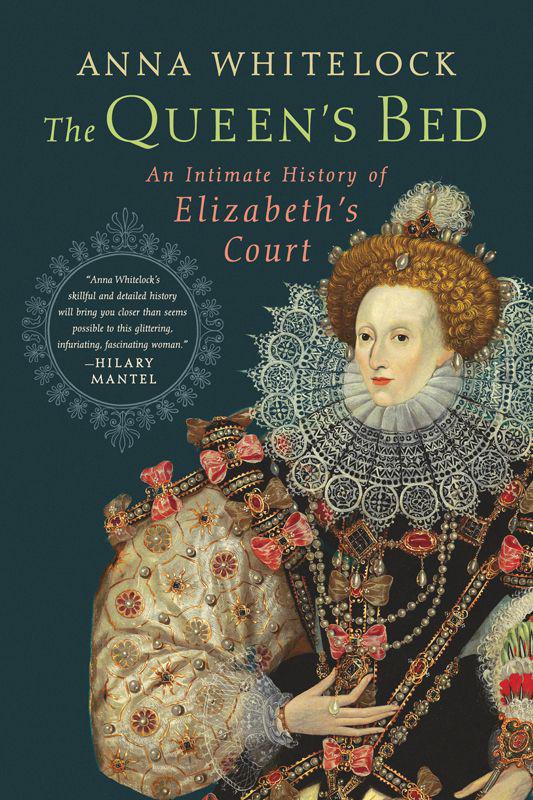

The Queen's Bed: An Intimate History of Elizabeth's Court

Read The Queen's Bed: An Intimate History of Elizabeth's Court Online

Authors: Anna Whitelock

Tags: #History, #Non-Fiction, #Biography

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way.

Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at:

us.macmillanusa.com/piracy

.

F

OR

K

ATE

We princes, I tell you, are set on stages in the sight and view of all the world duly observed; the eyes of many behold our actions, a spot is soon spied in our garments; a blemish noted quickly in our doings.

1

Elizabeth I

He did swear voluntarily, deeply and with vehement assertion, that he never had any carnal knowledge of her body, and this was also my mother’s opinion, who was till the XXth year of her Majesty’s reign of her Privy Chamber, and had been sometime her bedfellow.

2

John Harington, the Queen’s godson, on her relationship with Sir Christopher Hatton

The state of this crown depends only on the breath of one person, our sovereign lady.

3

William Cecil, Lord Burghley

CONTENTS

2. The Queen Is Dead, Long Live the Queen

35. In Defence of the Queen’s Body

45. Suspected and Discontented Persons

56. Dangerous and Malicious Ends

59. All Are in a Dump at Court

Author’s Note

The dates in this book are all, unless otherwise specified, Old Style – that is, according to the calendar introduced by Julius Caesar in 45

BC

. In February 1582 a new calendar was established by Pope Gregory XIII in a bull which prescribed that the day following 4 October 1582 should be 15 October, and that the new year should begin on 1 January instead of on Lady Day, 25 March. England, having repudiated papal authority, ignored the new calendar and, until 1751, English time continued ten days behind that of the Catholic states of Europe.

All quotations are in modern English spelling.

PROLOGUE:

Shameful Slanders

At thirteen, Elizabeth was serious yet striking, with fair skin, reddish-gold hair, a slender face and piercing coal-black eyes. A portrait from the time shows her in a crimson damask gown with long, wide sleeves and a magnificent underskirt richly worked in gold embroidery.

1

A tight bodice faintly outlines her breasts and offers the slightest hint of her burgeoning sexual maturity. Her face is framed with a French hood which, together with her necklace, dress and girdle, is trimmed with pearls – a symbol of her virginity. Her long slim fingers, adorned with rings, clasp a book of prayers with a ribbon marking a page within. She is standing in front of a bed; her body is thrown into sharp relief by the dark curtains which are pulled back on either side.

It was here, in Elizabeth’s Bedchamber, that one of the most formative incidents of her early life took place. For the first of many times, Elizabeth’s chastity became a subject of gossip, her body the object of rumour and speculation, and her Bedchamber a place of alleged sexual scandal.

* * *

Following the death of her father Henry VIII in January 1547, the teenage Elizabeth made her home with her stepmother Katherine Parr at the Old Manor in Chelsea, situated near the River Thames. Katherine and Elizabeth had grown close in the few years before, and shared similar intellectual and religious interests.

2

But their relationship was soon tested. In April, just four months after Henry’s death, Katherine married Thomas Seymour, uncle to the young King Edward VI and brother to Edward Seymour, now Lord Protector and Duke of Somerset.

3

He was a youthful and attractive forty-year-old bachelor. Tall, well built with auburn hair and a beard, Seymour was flamboyant, ruthless and insatiably ambitious. He had hoped initially to marry either the Princess Mary or Princess Elizabeth as a means of gaining power, but when he realised he would never secure the Privy Council’s consent, he turned to the next best thing, the queen dowager Katherine Parr. Katherine was reported to have been in love with Seymour for years, even before she married Henry VIII, and so responded enthusiastically to his advances. They married, in secret, in mid-April 1547 and Seymour now became Elizabeth’s stepfather, moving in with the princess and Katherine at Chelsea.

It was here that on many mornings during the next year, Thomas Seymour would go to Elizabeth’s Bedchamber, unlock the door and silently enter. If the princess were up he would ‘bid her good Morrow’, ask how she was and ‘strike her upon the back or the buttocks familiarly’. On other days, if Elizabeth was in bed, he would pull back the curtains and ‘make as though he would come at her’ and she would retreat to the furthest corner of the bed. One morning when he tried to kiss Elizabeth in her bed, her long-serving governess, Kat Ashley, ‘bade him go away for shame’.

4

Yet the encounters continued.

On one occasion when the household was staying at his London residence, Seymour made an early morning visit to Elizabeth in her Bedchamber, ‘bare legged’, wearing only his nightshirt and gown. Kat Ashley reprimanded him for such ‘an unseemly Sight in a Maiden’s Chamber!’ and he stormed out in a rage.

5

On two mornings, at Hanworth in Middlesex, another of Katherine’s residences, the queen dowager herself joined Seymour in his visit to Elizabeth’s Bedchamber and on this occasion they both tickled the young princess in her bed. Later that day, in the garden, Seymour cut Elizabeth’s dress into a hundred pieces while Katherine held her down.

6

The involvement of Katherine here is even more puzzling than that of the others. She had fallen pregnant soon after the marriage, so perhaps this made her jealousy more intense and her behaviour more reckless; maybe she was seeking to maintain Seymour’s affection and interest in her by joining in his ‘horseplay’. Perhaps she feared that Elizabeth was developing something of a teenage infatuation with her stepfather. In any case Katherine soon decided that enough was enough and in May 1548, Elizabeth was sent to live with Sir Anthony Denny and his wife Joan at Cheshunt, Hertfordshire. Denny was a leading member of the Edwardian government and Joan was Kat Ashley’s sister. Before Elizabeth left her stepmother’s house, Katherine, then six months pregnant, had pointedly warned her stepdaughter of the damage malicious rumours might do to her reputation.

7

Elizabeth was kept in seclusion at Cheshunt and this led to whispers that she was pregnant with Thomas Seymour’s child. Kat Ashley reported that the princess was only sick, but still the gossip continued. A local midwife claimed she had been brought from her house blindfolded to assist a lady ‘in a great house’. She came into a candlelit room and saw on a bed ‘a very fair young lady’ in labour. She alleged that a child was born and then killed. The midwife had assumed that it had been a lady of importance because of the need for secrecy. Knowing that Elizabeth was close by at Cheshunt, her suspicions were raised.

8

On 5 September, Katherine Parr died having fallen ill of puerperal fever a week after giving birth to a daughter, Mary.

9

Showing little grief for his wife’s death, Thomas Seymour began to pursue his political ambitions with renewed energy and revived his original plan to marry the Princess Elizabeth. Kat Ashley, after her earlier disapproval of Seymour’s behaviour as a married man, now became an enthusiastic supporter of a union between Seymour and her young charge. But when Protector Somerset became aware of his brother’s treasonous ambitions, Seymour was arrested and accused of plotting to overthrow the protector’s government and marry the King’s heir.

10

Days later, Kat Ashley and Sir Thomas Parry, Treasurer of the Household, were taken to the Tower and questioned by Sir Robert Tyrwhit, Master of the Horse in the household of Katherine Parr, as to what they knew of Seymour’s plotting and his plans to marry Elizabeth. When the princess was told of the arrests she was ‘marvellously abashed and did weep very tenderly a long time’. Whilst the interrogations went on, rumours intensified that Elizabeth was pregnant with her stepfather’s child. In a spirited letter to Protector Somerset of 28 January, she refuted the claims and urged the Privy Council to take immediate steps to prevent the spread of such malicious gossip: ‘Master Tyrwhit and others have told me that there goeth rumours Abroad, which be greatly both against my Honour and Honesty … that I am in the Tower and with Child by my Lord Admiral.’ These were, she continued, ‘shameful slanders’ which the council should publicly denounce. Elizabeth urgently petitioned the Lord Protector to allow her to come to court so that she could put pay to the accusations and show that she was not with child.

11

In an effort to crush her spirit and force her to confess, Kat Ashley was now taken to one of the darkest and most uncomfortable cells in the Tower; she begged to be moved to a different prison: ‘Pity me … and let me change my prison, for it is so cold that I cannot sleep, and so dark I cannot see by day, for I stop the window with straw as there is no glass.’ She remained loyal to Elizabeth, however, and revealed nothing of the goings on in the household or the princess’s relationship with her stepfather. ‘My memory is never good,’ Kat told her interrogators, ‘as my Lady, fellows and husband can tell, and this sorrow has made it worse.’

12